Banks Continue to Lend to the Financial Economy, Not the Real One

The financialization of the U.S. economy is evident in all manner of lending data

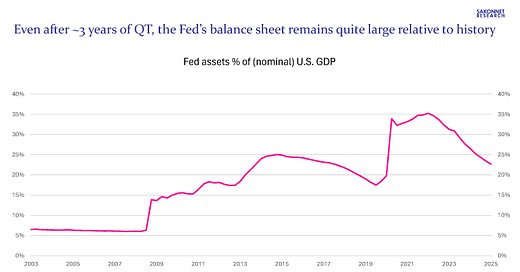

I’ve written on numerous occasions about the lack of vigor in the U.S. economy, which predated the current administration and all the uncertainty and tumult it’s caused. Yes, nominal and real GDP growth under the previous administration was healthy, but much of it came from unprecedented government spending/deficits and massive Federal Reserve (Fed) balance sheet/asset expansion. Even after nearly three years of balance sheet reduction (quantitative tightening, or QT) on the part of the Fed, its balance sheet was still nearly 23% of GDP in 1Q25, well above the 2019 average of 18% (was just 6% of GDP before the Great Financial Crisis, or GFC).

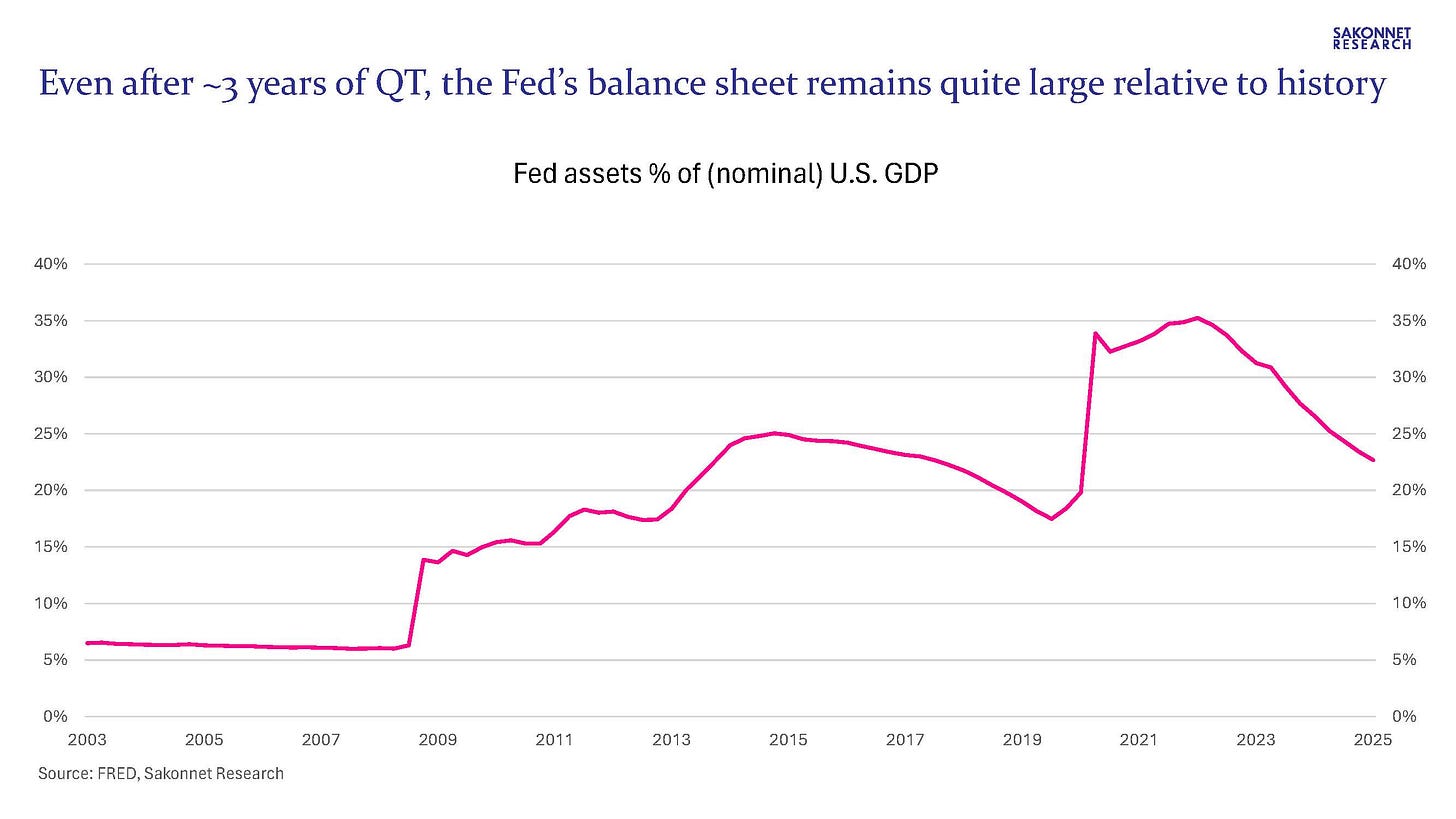

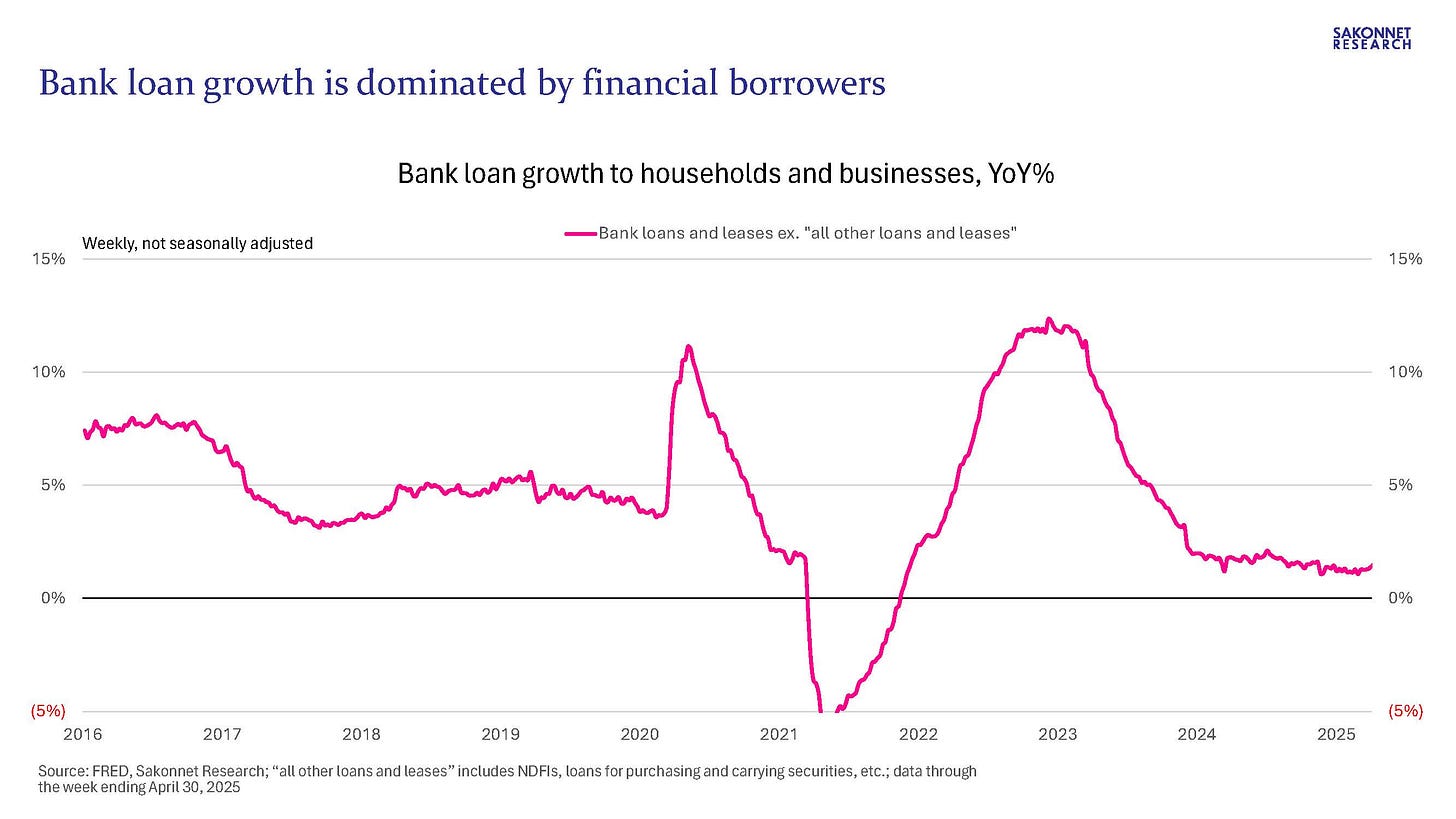

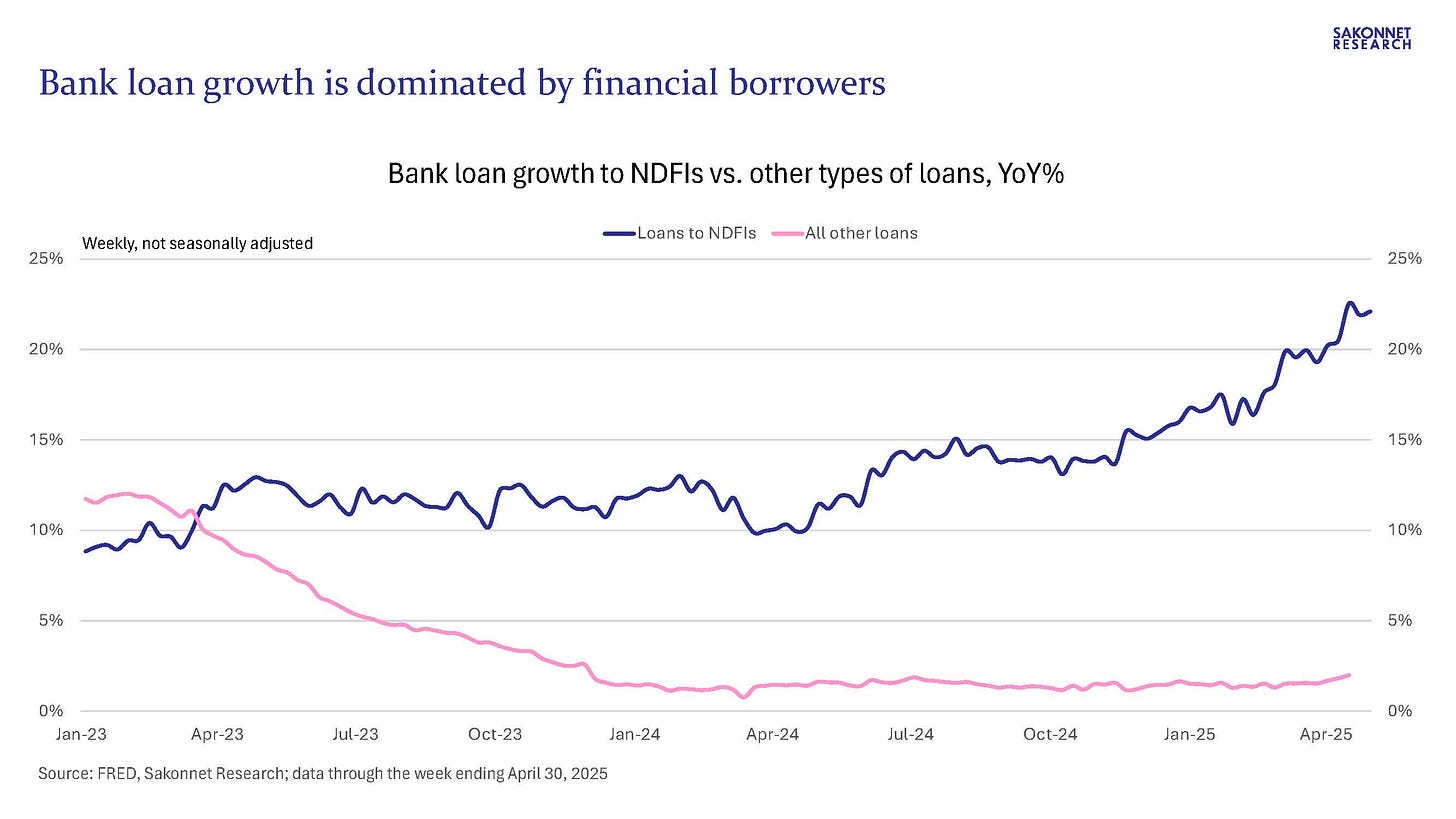

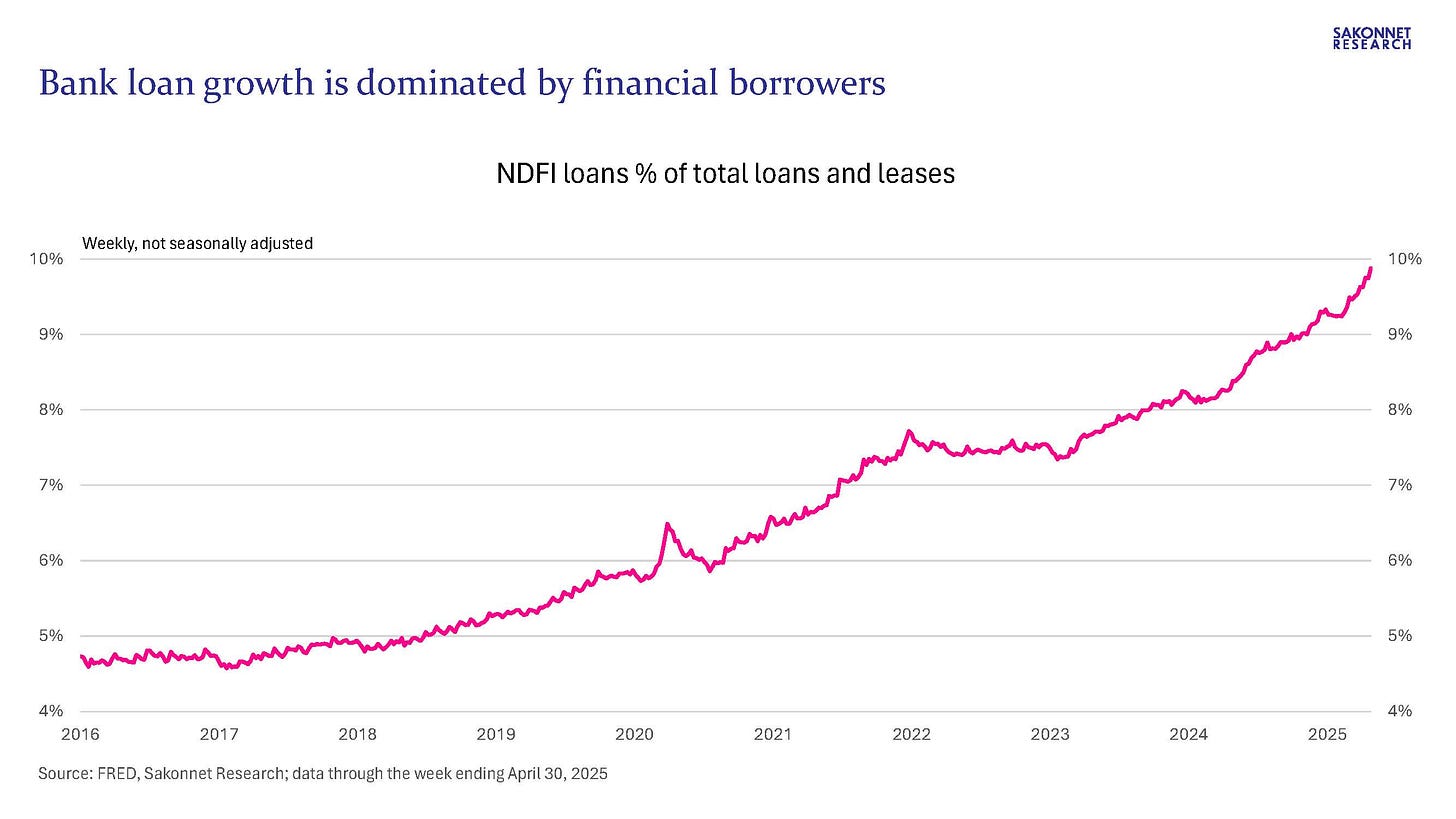

All the government and Fed stimulus supported the economy in the absence of much in the way of bank lending to the real economy, meaning businesses and households, particularly from 2024 onward; such loan growth has slowed to 1.5% over that period, dramatically below the 2016-2019 (pre-pandemic) average of 5%. For perspective, such loans (commercial & industrial loans, real estate loans and consumer loans) account for about 80% of total loans. What happened to the other 20% - “all other loans and leases” in the Fed’s weekly H.8 release, which largely consists of lending to financial institutions/entities - from 2024 onward? It grew by 7% compared to just 1.5% for real economy loans, and the growth rate has accelerated to 14% as of the most recent week. The trend is even more acute when looking at just loans to nondepository financial institutions (NDFIs), which account for just over 50% of the “all other” category: loans to NDFIs are growing by 22%, whereas all other bank loans are up just 2%.

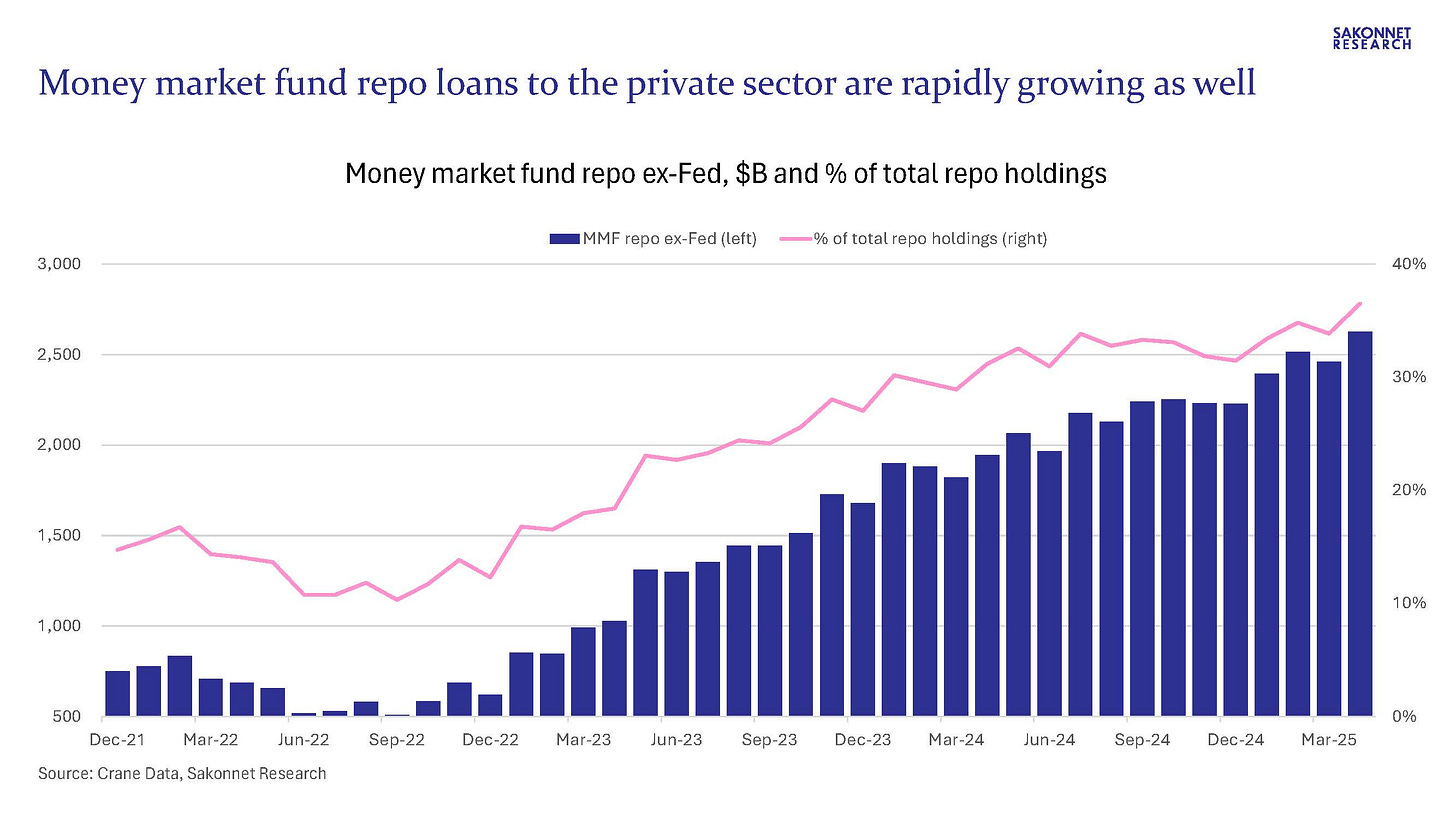

What’s going on? The financialization of the U.S. economy; banks are lending ever more money to broker-dealers, hedge funds, private equity/credit firms, securitization vehicles, etc., all part of the levered investment industry. The same trend is evident when looking at the composition of money market fund (MMF) holdings/assets; the growth in MMF repo lending to the private sector (the private sector defined in this case as all entities other than the Fed) has been meteoric over the past three years. The biggest repo borrowers by far are broker-dealers, which lend heavily to hedge funds via their prime brokerage units. Broker-dealers are also among the NDFIs to which banks have been lending an increasing amount of money to; we don’t know broker-dealers’ share of NDFI borrowing because that information isn’t available, but I assume it’s high. For perspective, commercial bank and MMF assets combined exceed $31 trillion, greater than nominal GDP; the lending behavior of those two industries has a profound impact on the real and financial economies.

So long as the financialization of the economy continues, there’s ample reason to expect the real economy to remain weak, particularly given a still-shrinking Fed balance sheet. Indeed, corporate sales, earnings and cash flow trends are deteriorating; as the Financial Times pointed out yesterday citing Citi research, 2025 EPS growth expectations for the S&P 1000 small- and mid-cap index have fallen substantially from the start of the year, from 5% then to just 1% today. As I’ve noted, the weakness in the real economy has lasted for years: witness the “freight recession” that’s been evident since early 2022 owing to protracted weakness in goods demand.

Despite the rapid bank and money market fund loan growth to the financial economy, there have nonetheless been widespread concerns about the stability of the U.S. Treasury market, prompting calls from Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, Fed Governor Michelle Bowman (who’s on track to become the Fed’s vice chair for supervision), financial industry associations and bank CEOs to exempt short-term or total Treasurys (short-term vs. total depending on the one making the argument) from large banks’ supplementary leverage ratio (SLR). Wrote the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) in April shortly after so-called Liberation Day:

With U.S. Treasury issuance set to grow rapidly, and with the current volatility in the market top of mind, we urge the Federal Reserve Board to exempt Treasuries from leverage ratio calculations to ensure banks can effectively intermediate the Treasury market.

In its call for an SLR exemption, SIFMA didn’t address what prompted the SLR in the first place, or what the potentially adverse consequences of an exemption may be. Fortunately, Sheila Bair, the former chair of the FDIC, did these very things in an opinion piece in the Financial Times two weeks later. In doing so, she said the move would “repeat old errors and encourage the buying of Treasury debt over private sector lending,” consistent with my point about the financialization of the economy.

Regarding the old errors to which she’s referring, she noted that regulators have long tried to limit banks’ use of leverage by requiring they maintain minimum levels of equity capital. Under “risk-based” standards, banks can boost their returns on equity by buying supposedly safe assets for which regulators require lower levels of capital. She pointed out, though, that banks’ ability to manipulate risk-based capital requirements is constrained by a required “leverage ratio” intended to serve as a safeguard in the event that risk-based requirements prove inadequate. Leverage ratios measure banks’ capital relative to their total assets, such that their assets aren’t risk-weighted.

Ms. Bair reminded us that the GFC was driven by bank capital rules that treated mortgages, including securities and derivatives tied to them, as low risk; this capital treatment fueled a massive U.S. housing bubble that eventually collapsed with nearly catastrophic consequences. As the Congressional Research Service (CRS), a public policy research institute of the U.S. Congress, noted in a March 2023 report:

Without risk weighting, banks would have an incentive to hold riskier assets, as the same amount of capital must be held against riskier and safer assets. But risk weights may prove inaccurate. For example, banks held highly rated mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) before the 2008 financial crisis, in part because those assets had a higher expected rate of return than other assets with the same risk weight. MBSs then suffered unexpectedly large losses during the crisis. Thus, the leverage ratio can be thought of as a backstop to ensure that incentives posed by risk-weighted capital ratios to minimize capital and maximize risk within a risk weight do not result in a bank holding insufficient capital.

The leverage ratio is simpler and more transparent than risk-weighted capital measures because the public does not have full information on the risk weight assigned to each asset held by the bank. Therefore, the public can less easily assess whether a bank has enough capital to absorb potential losses based on risk-weighted ratios. Some policymakers concluded after the 2008 financial crisis that boosting simpler, more transparent measures of capital can be better at restoring confidence during a crisis.

In other words, there were important reasons for global bank regulators to adopt leverage ratios as a backstop to risk-based requirements. Ms. Bair made another point besides: the argument that U.S. Treasurys should be considered “risk-free” beggars belief. They not only have interest-rate risk (depending on their duration) but also increasingly credit risk, as their volatility in the aftermath of Liberation Day made abundantly clear.

It’s self-evident why the Treasury Secretary along with banks, broker-dealers and hedge funds would want an SLR exemption. The Treasury Secretary has said he thinks Treasury bill (T-bill) yields could fall by 30-70 basis points in the event of an SLR exemption, which would lower the government’s (substantial and growing) borrowing costs.

An exemption would make it more profitable for (commercial) banks to hold Treasurys, which would limit their incentive to lend to the real economy (bearing in mind that their lack of lending to the real economy is already a problem). It would also help the broker-dealer subsidiaries of large bank-holding companies (BHCs) profit from ever-growing Treasury issuance, as market makers such as dealers benefit from higher activity. The same dealers lend heavily to hedge funds and other levered investors via their prime brokerage units, and that lending has been a major part of the financialization of the economy. As the Fed noted in its most recent Financial Stability Report (FSR) in April, hedge fund leverage was at or near the highest level in the past decade and concentrated in larger hedge funds. For whom is record-high hedge fund leverage a desirable state of affairs, aside from the hedge funds themselves and the primary dealers lending to them? As an aside, the Fed also pointed out that banks are sitting on major unrealized losses on their securities portfolios, which are mainly comprised of MBS and Treasurys; and we’re to believe that Treasurys are “risk-free” assets? Lastly regarding the FSR, the Fed stated that leverage at broker-dealers was near historically low levels. A few thoughts on that: (1) a mid to high teens leverage ratio isn’t objectively low by any standard; (2) according to the data I collected from primary dealers’ annual FOCUS reports filed with the SEC, primary dealers’ leverage ratio (defined as assets to equity) last year was near 30 times, not mid to high teens; (3) the leverage ratio excludes primary dealers’ substantial off-balance sheet derivatives exposures; and (4) the leverage ratio is calculated at quarter or year-end, such that it’s likely understated because of banks’ and broker-dealers’ commonly observed tendency to window-dress their balance sheets for regulatory reporting purposes. Broker-dealer leverage is quite high as is hedge fund leverage.

If all of this financial leverage eventually results in another crisis (bearing in mind there have been several since the GFC, specifically the COVID-19 crisis, 2019 repo crisis and March 2023 banking crisis), what will the Fed do? Its latest quantitative easing (QE) program, known as QE4, contributed to enormous growth in bank deposits and assets and historically high inflation (inflation has been above the Fed’s target level for over four years post-QE4). The latter was far from a desirable outcome, and the former arguably isn’t either, particularly considering to whom banks have chosen to increasingly lend (NDFIs and other such financial borrowers).

It’s worth noting that Roberto Perli, the manager of the New York Fed’s System Open Market Account (SOMA), gave a speech on Friday in which he pointed to recent improvements in the operations of the standing repurchase agreement (repo) facility (SRF) and the potential for more. Specifically, the NY Fed began testing early morning settlements to supplement the existing afternoon settlements, which he believes will “enhance the effectiveness of the SRF as a tool for monetary policy implementation and market functioning.” For those for whom the mention of the SRF draws a blank stare, it’s a Fed lending facility that complements its discount window lending facility. It enables primary dealers and banks to borrow short-term from the Fed using Treasurys, agency debt and agency MBS as collateral. The better the SRF and discount window work, the less incentive the Fed has to resort to QE as it’s done four times since the GFC.