For How Much Longer Will the Highly Leveraged Treasury Basis Trade Finance U.S. Budget Deficits?

A shaky foundation for the world's largest and most liquid market for government securities

The Federal Reserve (Fed) published an economic research piece last week titled “The Cross-Border Trail of the Treasury Basis Trade.” The title sounds bland enough, but the subject matter is anything but.

The authors begin, “Recent regulatory data collections on hedge funds indicate a massive increase in Cayman Islands hedge fund exposures to U.S. Treasury securities over the last two years, corresponding to a simultaneous surge in hedge funds’ Treasury cash-futures basis trade positions (the ‘basis trade’).” The U.S. Treasury publishes monthly statistics on foreign ownership of Treasurys (USTs)—the U.S. Treasury International Capital (TIC) data—but the authors found that hedge fund basis trade positions are dominated by hedge funds domiciled in the Cayman Islands, and that this activity is inadequately reflected in the TIC data. As a result, the TIC data “appear to severely undercount Cayman-domiciled hedge funds’ holdings of U.S. Treasuries by around $1.4 trillion as of the end of 2024…”

Specifically, from 2022 to the end of 2024, Cayman-domiciled hedge funds’ UST holdings had grown by $1 trillion to reach $1.85 trillion, compared to just $423 billion according to the TIC data. According to the authors’ figures, the Cayman Islands is by far the largest foreign holder of USTs, much bigger than China, Japan and the UK, the three largest holders displayed in Treasury’s “Major Foreign Holders” table. Assuming that most Cayman-domiciled hedge funds’ UST holdings are tied to the basis trade, it accounted for nearly 6.5% of USTs outstanding at year-end 2024.

The authors also found that from 2022 to the end of 2024, amid the Fed’s quantitative tightening (QT)/balance sheet reduction program, Cayman Islands hedge funds purchased a net $1.2 trillion of USTs. Assuming these were all notes and bonds (rather than bills), these purchases absorbed 37% of net issuance of notes and bonds, “nearly the same amount as all other foreign investors combined.”

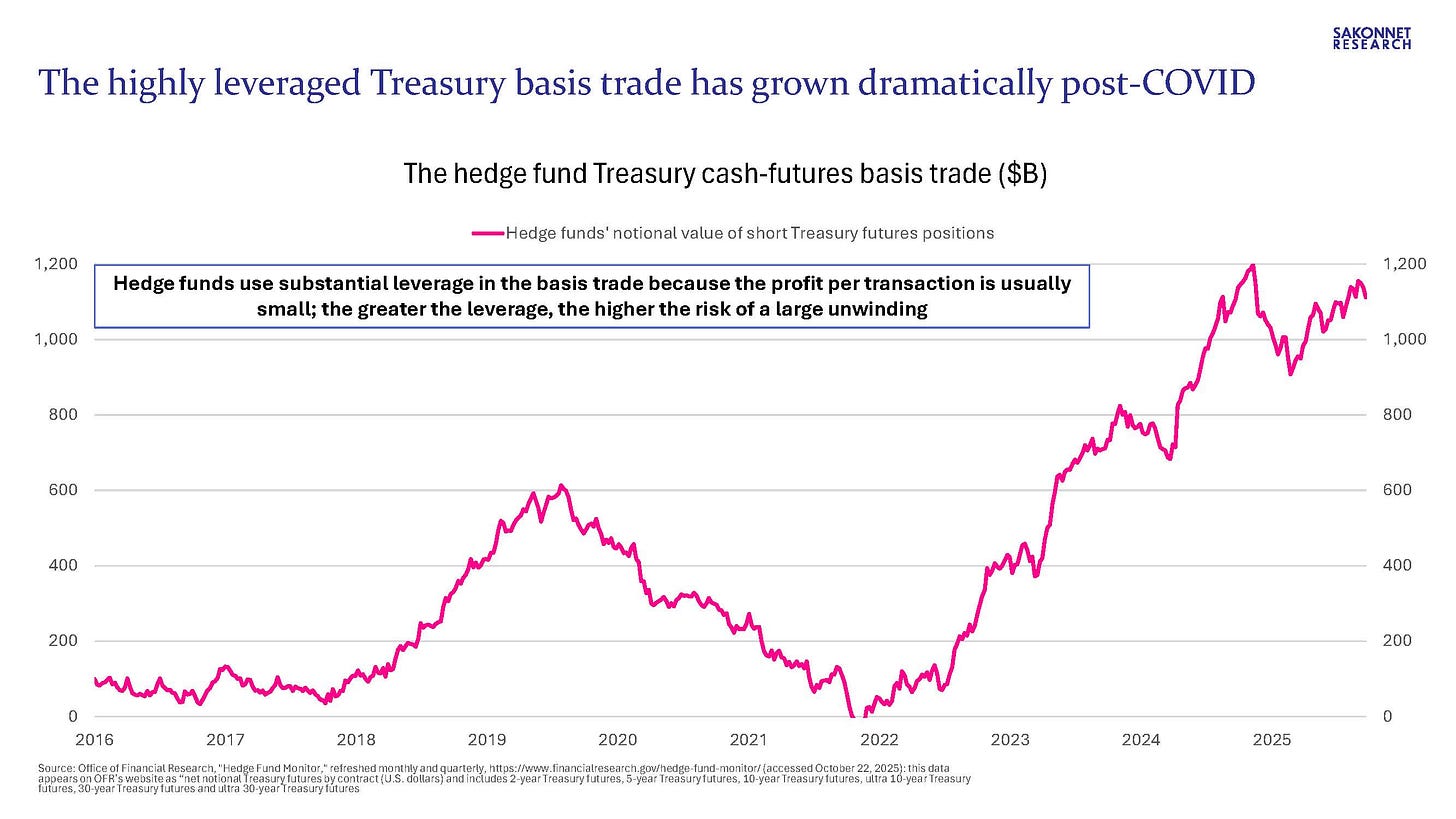

For background on the ballooning basis trade (I’ll spare you the technical details), hedge funds use substantial leverage to finance it given that the profit per transaction is usually small; FT Alphaville estimated as much as 50x leverage is normal and that up to 100x can happen (link). How do hedge funds finance these trades? By borrowing in the repurchase agreement (repo) market from highly leveraged broker-dealers and pledging the purchased USTs as collateral, usually via bilateral repo (including sponsored repo). Per the Office of Financial Research (OFR), hedge funds borrowing cash comprise most sponsored repo volumes, whereas money market funds (MMFs) lending cash comprise most sponsored reverse repo volumes. (More on sponsored repo in a subsequent post; it’s becoming an increasingly important topic.)

Why should market participants care about this, particularly if the Fed stops QT in “coming months” as Chair Jerome Powell suggested may happen in a speech last week? Well, even if it does, the current pace of QT/balance sheet runoff is only ~$20 billion per month compared to net UST issuance of ~$160 billion per month over the past year, such that doing so won’t have a demonstrable impact on UST demand. And the Fed has given no indication that it intends to revert to yet another quantitative easing (QE) program anytime soon, such that other buyers will have to absorb the substantial ongoing UST issuance. For perspective, the Fed owned ~25% of USTs outstanding in 2021/2022 post-QE4, and 15% as of year-end 2024 per SIFMA data. The Fed remains the largest single holder of USTs following its numerous rounds of QE, and by a wide margin.

Along those lines, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) will publish its updated deficit forecasts in early 2026, which will include the estimated impacts of the 2025 reconciliation act (OBBB), tariffs and immigration. In January 2025, the CBO projected ever-growing deficits through 2034, bearing in mind that the U.S. budget deficit in fiscal year 2025 was a substantial $1.8 trillion. And the CBO estimated after the passage of the OBBB that the bill will increase budget deficits by $3.4 trillion over the 2025-2034 period compared to its January 2025 baseline. In other words, there’s a great deal of UST issuance/supply on the come that someone will need to finance.

Who will that someone be absent the Fed, and at what price/interest rate? MMF assets are at a record-high $7.793 trillion per Crane Data and growing, and MMFs are a large UST holder. That said, MMFs mostly own bills rather than notes or bonds, and bills only account for 21-22% of USTs outstanding (notes and bonds account for most of the remainder). MMFs owned 10% of USTs outstanding as of year-end 2024 per Crane Data and SIFMA data, including ~38% of bills outstanding.

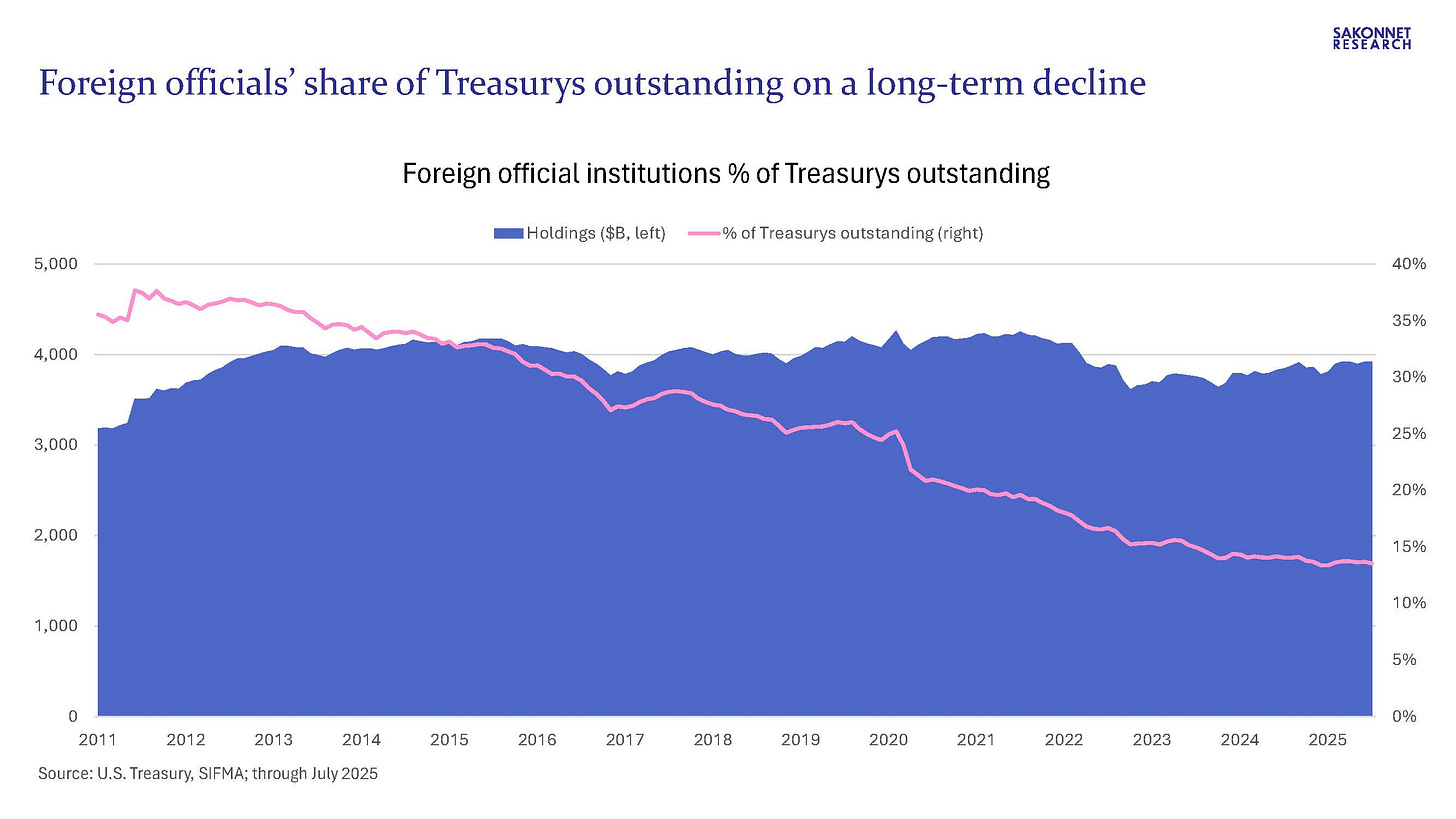

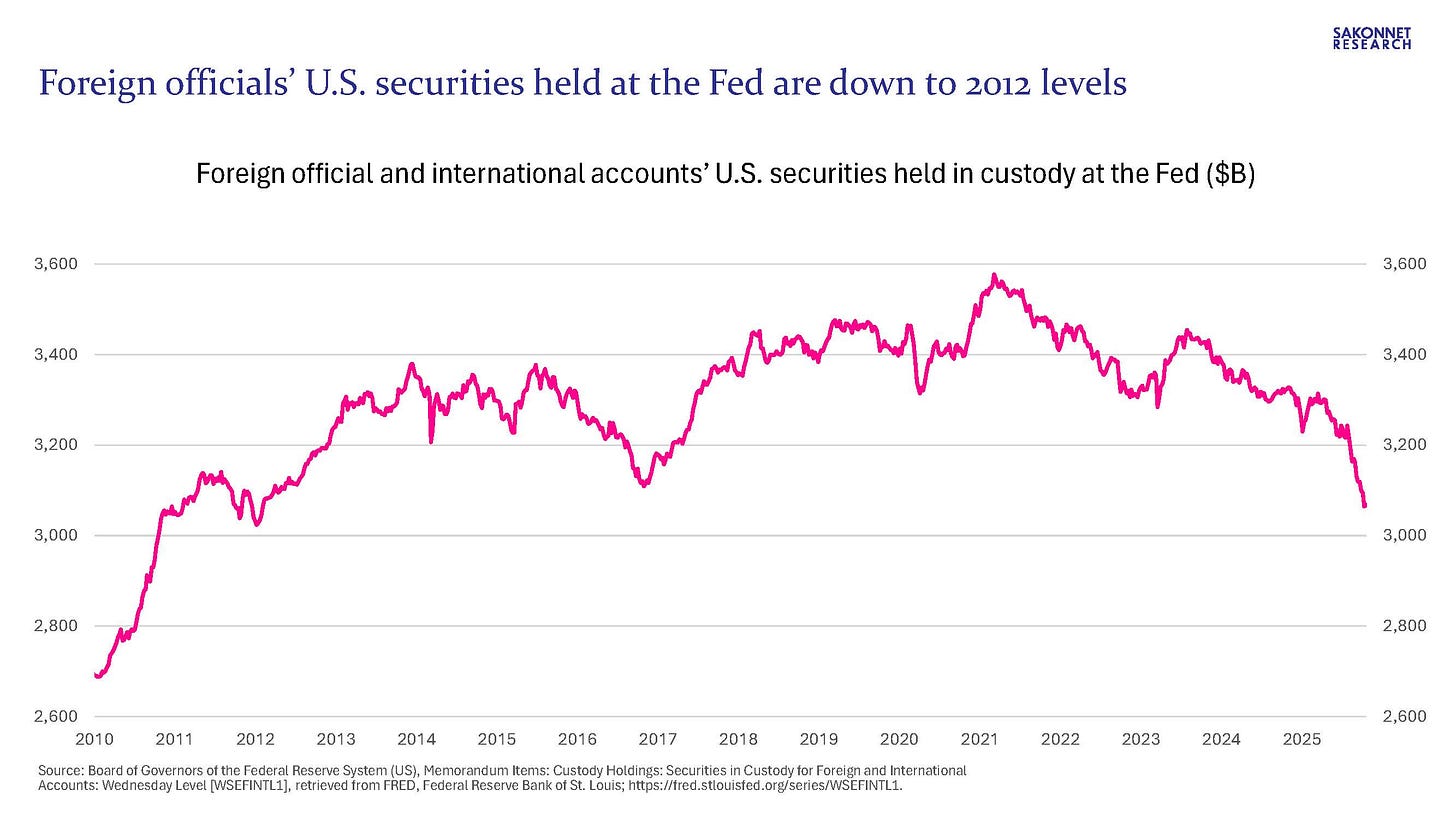

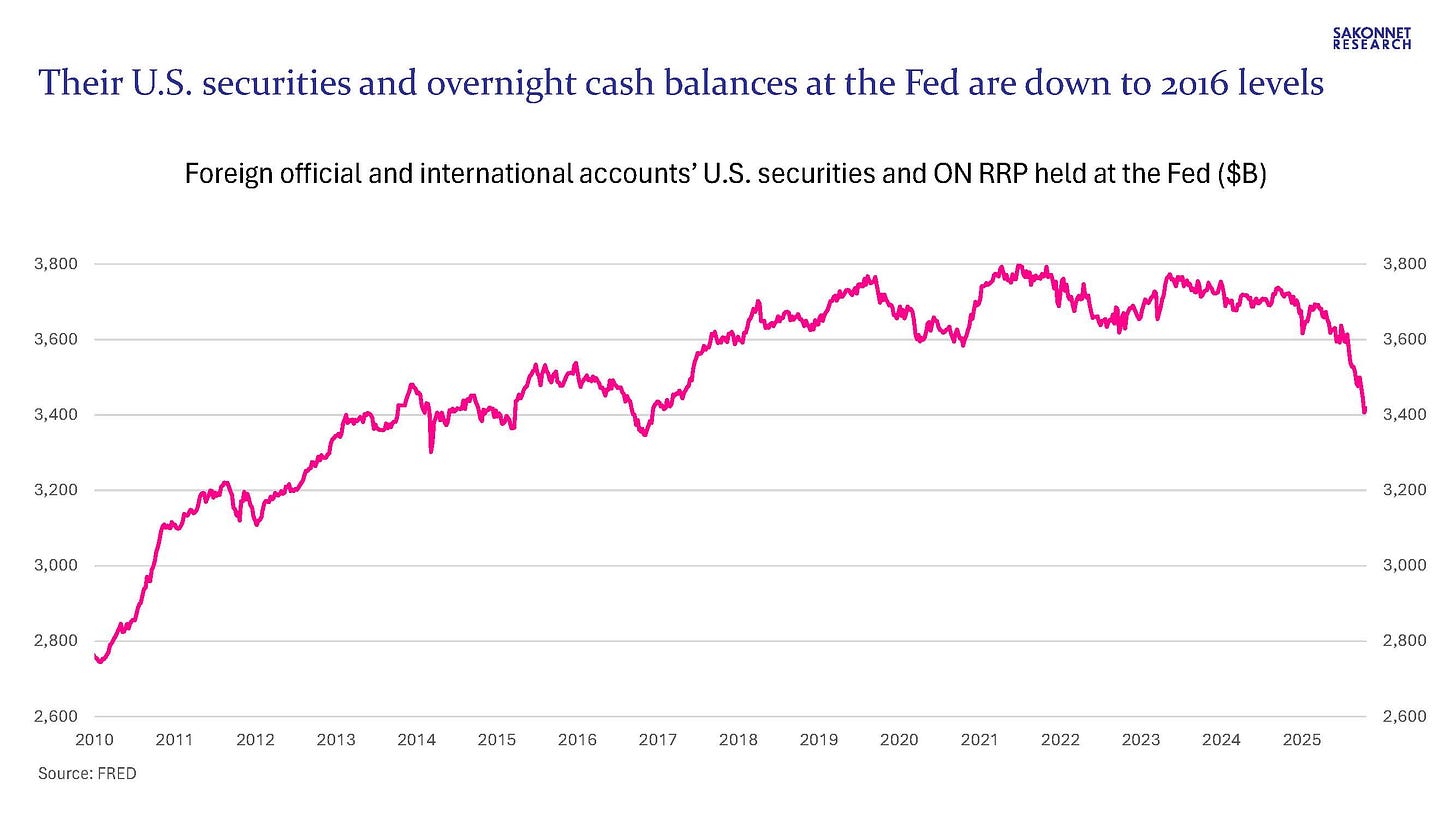

The highly leveraged hedge fund basis trade could continue to grow, but so too could it unwind; it was partly unwound in March 2020 in response to problems in the UST and repo markets. Foreign officials (foreign central banks) own fewer USTs than they did a decade ago, and more timely data from the Fed’s weekly H.4.1 release indicates that these entities’ U.S. dollar holdings (securities and cash) at the Fed are at their lowest level since 2016. Why are foreign central banks pulling dollar-denominated assets out of the Fed? Either because they want to diversify out of U.S. assets or because they need the dollars in their (weak) domestic economies. Foreign officials owned just over 13% of USTs outstanding at year-end 2024.

I’ve covered the Fed, MMFs, hedge funds and foreign officials among potential UST buyers. Who am I leaving out? Banking institutions, which held 8% of USTs outstanding at year-end 2024 per SIFMA data. Other, smaller holders include pension funds, insurance companies, and state and local governments. All would be logical UST buyers at higher rates. Banks, for instance, care about maximizing their risk-adjusted returns and have a choice between making a loan, buying USTs/agency securities, and parking cash overnight at the Fed and earning interest on reserve balances (IORB).

In other words, there likely won’t be a shortage of buyers of notes and bonds even if the basis trade were to unwind, foreign officials were to continue to refrain from buying, and/or the Fed were to refrain from additional QE. The issue is, at what price/interest rate? Could long-term interest rates go much higher if one or more of these things were to happen? Yes. And what would happen in that case? Borrowing costs for consumers and businesses would go up, a lot.

The content in As the Consumer Turns newsletters should not be construed as investment advice offered by Adam Josephson. This market commentary is for informational purposes only and is not meant to constitute a recommendation of any particular investment, security, portfolio of securities, transaction or investment strategy. The views expressed in this commentary should not be taken as advice to buy, sell or hold any security. To the extent any content published as part of this commentary may be deemed to be investment advice, such information isn’t tailored to the investment needs of any particular person. No chart or graph provided should be used to determine which securities to buy or sell.