The Fed Continues to Focus on Risks Associated With NDFI Lending

NDFIs and hedge funds the subject of this year's "exploratory analysis" of the banking system

The Federal Reserve (Fed) yesterday released the scenarios for its 2025 stress test, which evaluates the resilience of large banks by estimating losses, net revenue and capital levels under hypothetical recession scenarios two years into the future. This year, 22 banks will be tested. Alongside the stress test is an exploratory analysis that will examine shocks in the non-bank/non-depository financial institution (NBFI/NDFI) sector as well as the impact of the hypothetical failure of five large hedge funds. The exploratory analysis won’t affect large bank capital requirements, but it’s apparent that the Fed is paying increasing attention to the issue of NDFI lending, with unknown future consequences.

I’ve written several times in recent months about rapidly growing U.S. bank lending to NDFIs such as broker-dealers, hedge funds, private credit firms and securitization vehicles (essentially leveraged investment funds). The recent growth is eye-opening: loans to NDFIs are growing by nearly 20% YoY, compared to less than 2% YoY for all other loans. For perspective, loans to NDFIs account for just 9% of bank loans but ~50% of bank loan growth in recent months.

I’ve also noted that bank regulators have been paying increasing attention to this rapid growth. The Liberty Street Economics blog, which is analysis from NY Fed economists, published three articles within a week last June analyzing the close relationship between banks and NDFIs. Around the same time, the Fed published a proposal seeking more specific data from banks regarding their exposures to NDFIs, which was in banks’ recently-filed 4Q call reports (more to come on that in a subsequent post).

Back to the exploratory analysis, the Fed noted that U.S. bank exposures to NDFIs have grown rapidly over the past five years and that large banks’ credit commitments to NDFIs reached about $2.1 trillion in 3Q 2024. The Fed continued, “This growth poses risks to banks, as certain NBFIs operate with high leverage and are dependent on funding from the banking sector.” Prominent among such NDFIs are broker-dealers. And as the Fed is well aware, banks and broker-dealers are often part of the same entity; roughly half of broker-dealer assets are with bank holding companies (BHCs).

The first element of the Fed’s exploratory analysis considers what could happen to banks in the event of a shock to NDFI borrowers during a severe global recession. The stresses contemplated are (1) the rapid deterioration in the credit quality of assets held by highly leveraged NDFIs that provide credit (to hedge funds, among other investment funds/vehicles), leading to downgrades in their own credit ratings; and (2) NDFIs, which historically rely more heavily on bank lines of credit in times of stress, draw more heavily on their credit lines with banks. The second element of the exploratory analysis considers what would happen to banks in the event of the failure of five large hedge funds. There’s a direct link between NDFIs and hedge funds: large broker-dealers are among the biggest NDFIs, and hedge funds rely on broker-dealers for leverage, securities lending, etc.

With bank loan growth to NDFIs dwarfing that to households and businesses, it’s no wonder that the financial economy is dramatically outperforming the real economy, as evidenced by historically high equity, cryptocurrency and gold prices amid weak sales and earnings trends in many sectors (notably Consumer Staples, Materials, Industrials and Energy). However, the NDFI loan growth is attracting growing attention.

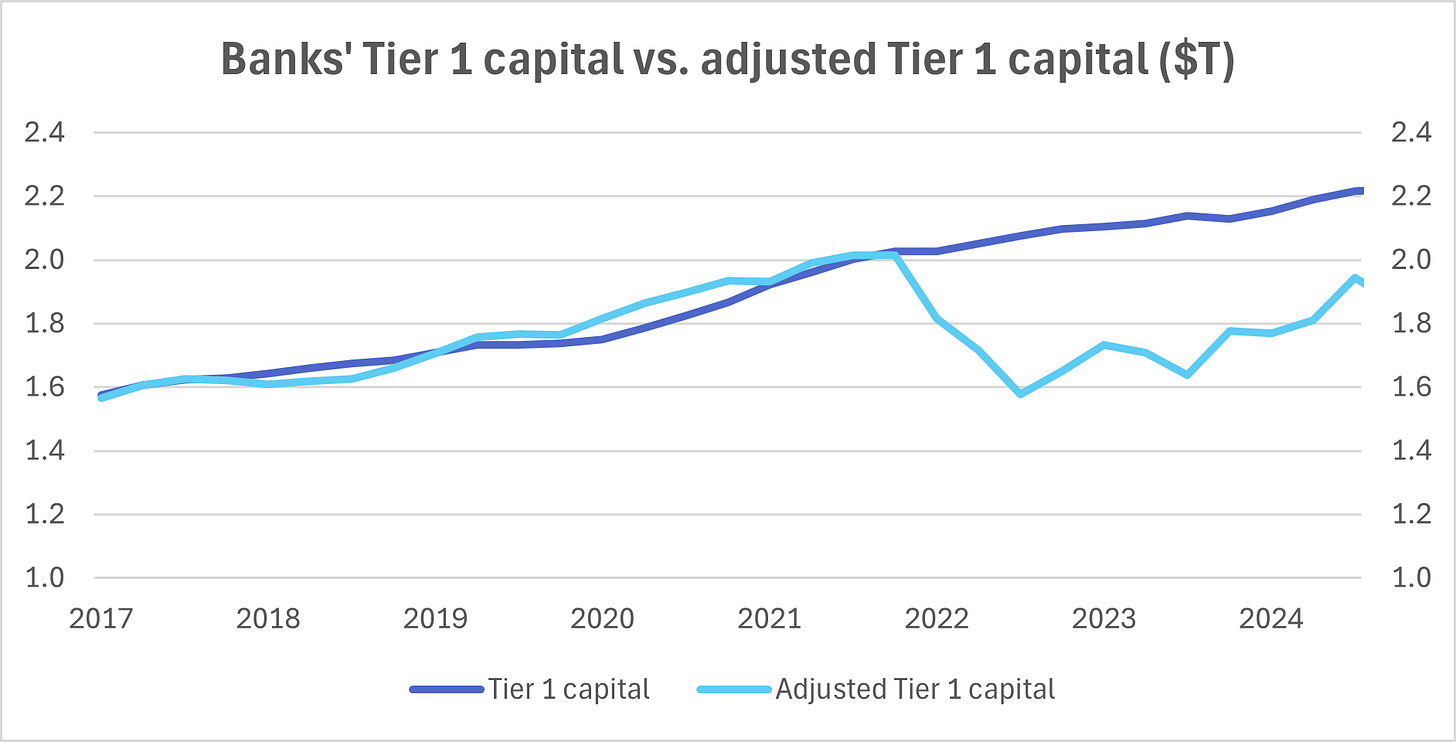

Furthermore, there’s ample reason to wonder how long the rapid loan growth to NDFIs can continue having nothing to do with increased regulatory attention. Lending money to leveraged investment funds that in some cases are dependent on funding from the banking sector strikes me as inherently riskier than lending to households and businesses. And at the same time as banks are making more of these loans, they’re sitting on substantial unrealized losses on their available-for-sale (AFS) and held-to-maturity (HTM) securities. Per BankRegData (with the vast majority of 4Q call reports having been accounted for), unrealized losses as of 4Q were $482.4 billion, representing nearly 22% of banks’ Tier 1 capital of $2.22 trillion. (Tier 1 capital is the strongest form of bank capital.) In the last six years, banks’ Tier 1 capital has grown by 32%. However, after adjusting for unrealized losses (which includes tax-effecting the losses and adding back a modest amount of estimated losses that are already reflected in banks’ AOCI and consequently Tier 1 capital), it only grew by 12%. Over the same period, banks’ assets are up nearly three times the adjusted capital amount (35%). In other words, banks’ adjusted capital isn’t remotely keeping pace with its loan and securities growth.