What Food and Tampon Demand is Telling Us About the Economy

Recent GDP growth has been propelled by healthcare and government spending, not by discretionary consumer spending

As a longtime paper & packaging industry analyst, my focus for much of my career has been on goods spending, which accounts for 20%-25% of U.S. GDP. Goods spending after adjusting for inflation has grown by just ~0.5%/yr. over the past three years, not surprisingly considering the boom that resulted from the combination of stay-at-home behavior and unprecedented government stimulus spending in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. All manner of public companies tied to goods spending have reported pronounced volume weakness over the past couple of years: freight companies (rail and truck), parcel delivery companies (UPS and FedEx), consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies, paper & packaging companies, retailers, etc.

Take food as an example. Food is the most basic good people buy, and contrary to what many assume (that Americans can’t be eating less), Americans are buying increasingly less of it. According to an economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Americans spent 3.1% less on food at home in 2023 than in 2022 adjusted for inflation. And according to NielsenIQ data per the same article in The Financial Times, checkout terminals at U.S. stores scanned 1% fewer items in the past 12 months to June compared to the previous year and 7.5% fewer items than in the year leading up to June 2020. Another example is sanitary pads and tampons: annual U.S. unit sales have fallen by 12% and 16%, respectively, since 2020, according to NielsenIQ data cited in a recent article in The Wall Street Journal. U.S. tampon prices are up an eye-opening 36% over the past five years, well in excess of consumer price inflation during that period. (Tampon demand has also been adversely affected by increasing usage of pads as well as by health concerns, which I was unaware of until a recent Bloomberg article pointed them out.)

If you have difficulty believing these numbers, food companies’ second-quarter results may convince you. Hershey just reported a 22% (!) volume decline in its North America confectionary segment as consumers are “pulling back on discretionary spending.” Hershey, Nestle, Kraft Heinz, Church & Dwight and PepsiCo all lowered their 2024 sales guidance this quarter, a highly unusual development for a group of companies that sell products for which demand is supposedly stable. (PepsiCo tweaked its language from “at least” 4% organic sales growth to “approximately” 4%, while the other changes were outright reductions.) On a similar note, Amazon missed analysts’ second-quarter sales forecasts and guided below consensus estimates on sales for the third quarter, with the company acknowledging its sales in North America were below its internal estimate and noting that consumers are “continuing to be cautious in their spending and trading down to lower ASP (average selling price) products.”

I’ll expand on these issues in subsequent posts. Suffice it to say, though, that the goods economy hasn’t been the source of anyone’s optimism regarding the economy over the past two years.

What has been, in that case? Services and government spending. I mentioned earlier the fact that goods spending accounts for 20%-25% of GDP; services spending accounts for another ~45%, gross private domestic investment ~17%, and government spending ~17%. (Net exports are a modest drag on GDP, which is why the numbers don’t sum to 100%.) Services spending has bounced back sharply following its pandemic-driven plunge: from 2021 to 2023, inflation-adjusted (real) services spending was up 6.1%, compared to real GDP growth of 4.5%.

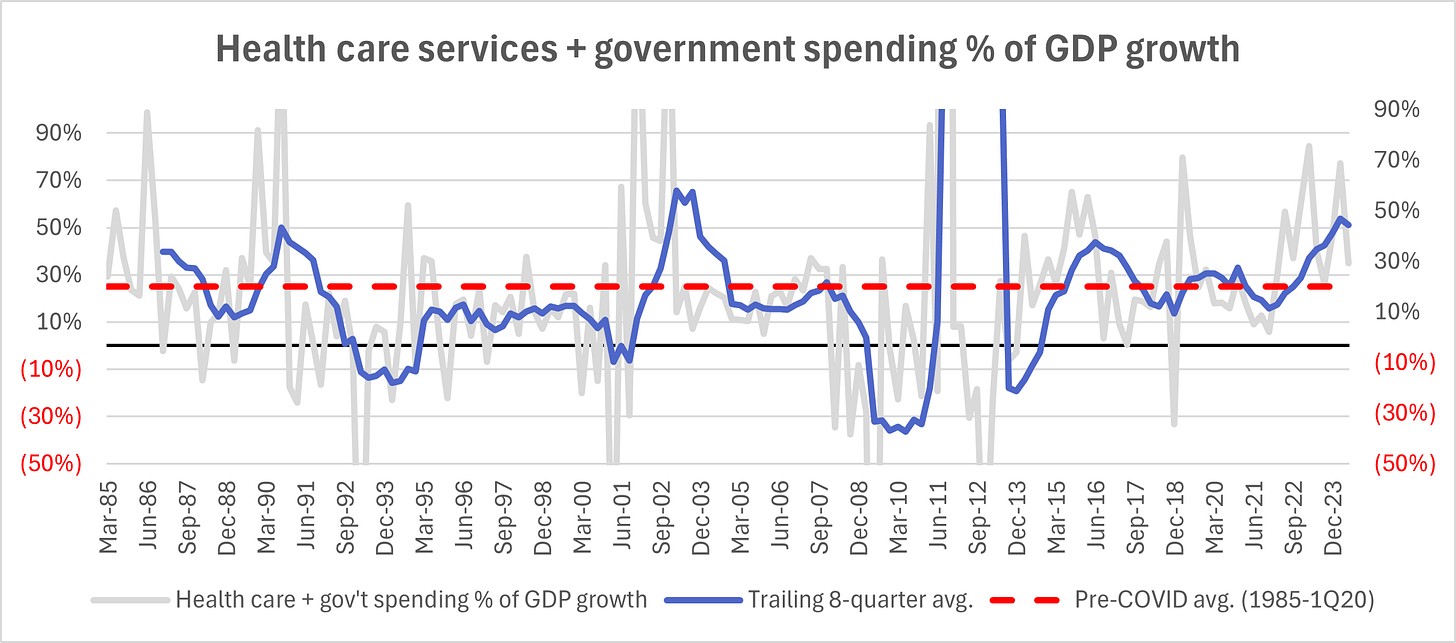

Government spending has been a consistent contributor to real GDP growth since then as well, and that doesn’t even include the substantial boost to domestic manufacturing activity resulting from the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and CHIPS and Science Act.

The government’s recent contribution to GDP growth comes as no surprise given that the U.S. federal deficit as a percentage of GDP is higher than in any period in the past half-century with the exceptions of the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. government has historically run major deficits during wartime, recessions and pandemics, not in the fourth year of an economic recovery as Jim Bianco has pointed out. Even if the government continues to run historically large peacetime deficits and add to its rapidly growing debt pile, that wouldn’t necessarily be stimulative to consumer spending considering that the deficits likely wouldn’t be any larger than they already are. Furthermore, the government’s ballooning interest expense on its debt is increasingly crowding out discretionary spending.

The services contribution to recent GDP growth is the more interesting subject. Many associate services spending with traveling, going to restaurants, Taylor Swift concerts, etc., in other words discretionary spending. However, much of it is on nondiscretionary categories including healthcare, housing and utilities, and financial services and insurance. Post-COVID, healthcare services spending has taken on an outsized role in the economy: over the past two years, it has accounted for fully half of consumer spending growth, bearing in mind that consumer spending accounts for nearly 70% of GDP (h/t to Parker Ross at Arch Capital Group for bringing my attention to this fact via his posts on X).

Americans are all too aware of the inflation that’s been occurring in housing and insurance costs as well, which, along with healthcare costs, have been consuming an ever-growing share of their incomes (with the notable exception of those many homeowners who had the foresight to take out a 30-year fixed rate mortgage before the Federal Reserve embarked on its interest rate increase campaign). Below is a chart of home and auto insurance premiums; they’ve been growing at their fastest rate in over two decades, the result of widespread natural disasters and higher interest rates.

Another illustration of the unusual and likely unsustainable nature of recent GDP growth is the combined share of health care services and government spending: those two categories have accounted for 50% of GDP growth over the past two years, compared to the pre-COVID average of just 25%.

Americans have only so much money to spend, and many appear to be spending all of it on necessities. Consequently, the lack of spending growth on discretionary goods and services makes ample sense. What of the notion that Americans are still spending plenty of money on travel and entertainment? On the one hand, airline passenger traffic in the U.S. has been setting records this year, leading some economists and others to conclude that discretionary spending remains robust. On the other, all the biggest U.S. airlines either cut their second quarter revenue guidance (American, Southwest, and Spirit Airlines), gave downbeat guidance for the third quarter (Delta, United, and Alaska Airlines), and/or cut their full-year guidance (American) as U.S. airfares continue to fall. Booming demand typically leads to price increases, not declines.

What about restaurant spending? U.S. restaurant same-store sales trends have stagnated or worse thus far in 2024 judging by a wide variety of public companies’ results, and many restaurant operators have made it clear that many Americans are under increasing financial strain. McDonald’s on Monday reported its first global and U.S. same-store sales decline since 2020 as U.S. traffic fell. Lamb Weston, one of the world’s largest producers of frozen french fries, noted just over a week ago that demand declines had “accelerated” in recent months and would likely continue into its next fiscal year (its fiscal year ends in May). Said the company in its earnings release on July 24th, “The operating environment has changed rapidly over the past twelve months as global restaurant traffic and frozen potato demand softened due to menu price inflation continuing to negatively affect global restaurant traffic.”

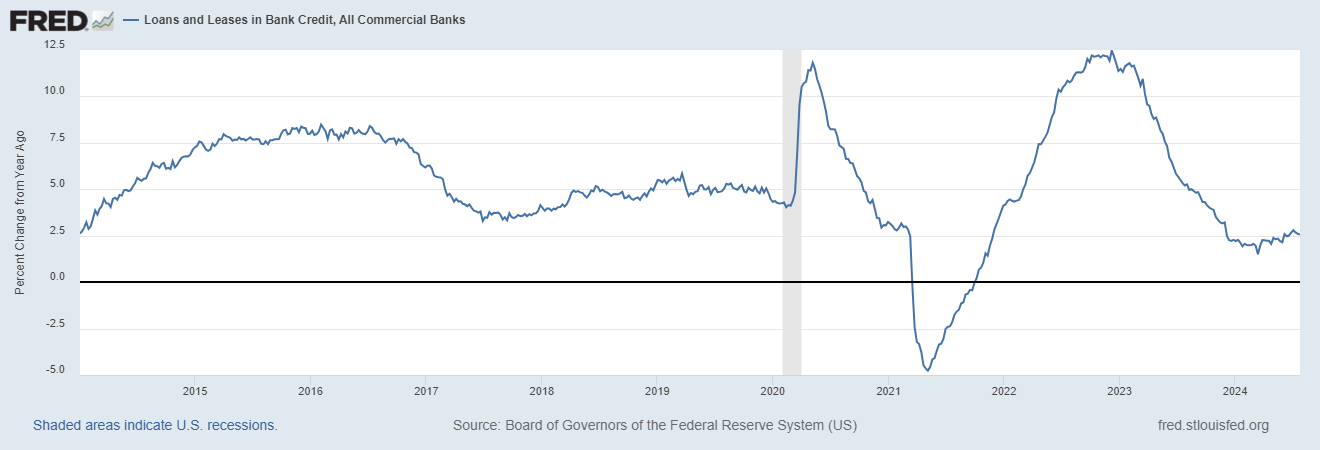

Why the consumer malaise in that case? Personal saving rates are near record-lows; the rate of 3.4% in June was well below the historical average of 8.4%. Real average weekly earnings are essentially flat vs. pre-pandemic levels (because of historic inflation), such that the country has made discernible no income progress since then. And bank loan growth has slowed to its lowest level in a decade aside from the COVID-19 pandemic period.

The obvious question one may ask in response to the latter is why. I believe it’s the confluence of three factors: (1) banks' willingness to lend is dependent on their ability to earn a sufficiently high risk-adjusted return, and rising delinquencies on consumer, commercial real estate (CRE) and other loans could be making banks increasingly risk-averse; (2) the ability of companies and individuals to borrow has been constrained by the recent substantial increase in interest rates coupled with deteriorating economic conditions; and (3) banks' lending capacity in some cases is constrained by their lack of capital/shareholders' equity, particularly when taking into account major unrealized losses on their held-to-maturity and available-for-sale securities ($516.5 billion in the first quarter, which represented 20%-25% of their equity capital).

The only category of bank loans that’s been growing to any appreciable extent in recent months has been loans to nondepository financial institutions (NDFIs), which include private credit firms; those loans are growing at a rate of 10%-11%, well in excess of the rate of total loan growth. And this rapid growth is causing concern among U.S. banking regulators. Noted the Federal Reserve System in June, “U.S. bank exposures to NDFIs have grown rapidly over the past five years and reached about $2 trillion in the fourth quarter of 2022. This growth poses risks to banks, as certain NDFIs operate with very high leverage and are dependent on credit from the banking sector. Currently, data on exposures to NDFIs are limited on the FR Y-14, as banks report minimal information about these obligors, relative to other corporate borrowers. This lack of data hinders staff’s ability to consistently measure, monitor, and model the risks stemming from these exposures under stress.”

I haven’t come across much discussion of what’s most likely to propel the next (discretionary) consumer spending boom, perhaps because many assume it will be yet more government stimulus spending despite the government’s ballooning interest expense on its debt. If anyone has thoughts along those lines, please don’t hesitate to share them with me; perhaps they could be fodder for a future article. Thank you for reading, and please share with friends and colleagues if you feel so inclined.

My best, Adam