Where Have the Boxes Gone?

A brief diversion from writing about banking/the Fed

I’ve written extensively about mushrooming U.S. bank lending to nondepository financial institutions (NDFIs) such as bank-affiliated broker-dealers, hedge funds, private credit/equity funds and securitization vehicles at the expense of the real economy (businesses and households), the result of regulatory arbitrage. It’s not just changing lending preferences that have adversely affected the provision of the credit to the real economy; so too have post-Great Financial Crisis (GFC) liquidity requirements that have prompted banks to hold more cash and securities than they used to. It should come as no surprise, then, that banks’ share of nonfinancial corporate borrowing has been on a steady decline in recent years, and that the financial sector has become far larger during the same period (reflected in historically high valuations/prices of numerous asset classes). I’ll resume writing about the banking industry and its alphabet soup of acronyms in short order.

What I haven’t written nearly as much about is the tangible impact of these developments on the real economy. One example is the sector I used to cover while a sell-side analyst, paper & packaging.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) under former Chairman Alan Greenspan used to monitor corrugated box demand as a sign of how the economy was performing; boxes are used to ship goods, and goods spending accounted for nearly 25% of GDP in the early 2000s (down to 21% now). Box demand isn’t a perfect proxy for goods demand owing to ongoing substitution among large e-commerce retailers from boxes to flexible mailers and other types of packaging (see page 31 of Amazon’s 2023 Sustainability Report for details) along with other factors, but it nonetheless reflects goods demand to a significant extent.

Goods and therefore box demand surged during the pandemic thanks to unprecedented government deficit spending and massive Fed stimulus coupled with stay-at-home behavior, and the hangover has been fierce. There’s been a U.S. freight recession since early 2022 as goods demand normalized from its pandemic highs, and U.S. box shipments fell by 4% in both 2022 and 2023 to below pre-pandemic levels (link), were flattish last year (link), and are falling again in 2025 (down 2% in 1Q). How are U.S. producers of containerboard (the raw material for boxes) responding? In the first half of 2025, five of them announced permanent containerboard mill closures totaling ~2.5 million tons of capacity, representing nearly 6% of 2024 N.A. capacity (link). The most recent closure announcement was earlier this week (link).

Not even in 2008/2009, when the global financial system nearly collapsed, did U.S./N.A. producers permanently shut nearly this much production capacity in a year. In 2009, International Paper shut two containerboard mills and a machine at a third mill, totaling 1.4 million tons of capacity (link). The obvious question is how the U.S. containerboard industry ended up with so much apparent excess capacity, particularly at a time of economic expansion rather than contraction; that’s beyond the scope of this post, but it’s likely the result of numerous factors (domestic demand, export demand/prices, and the age and capital requirements of the mills being shut).

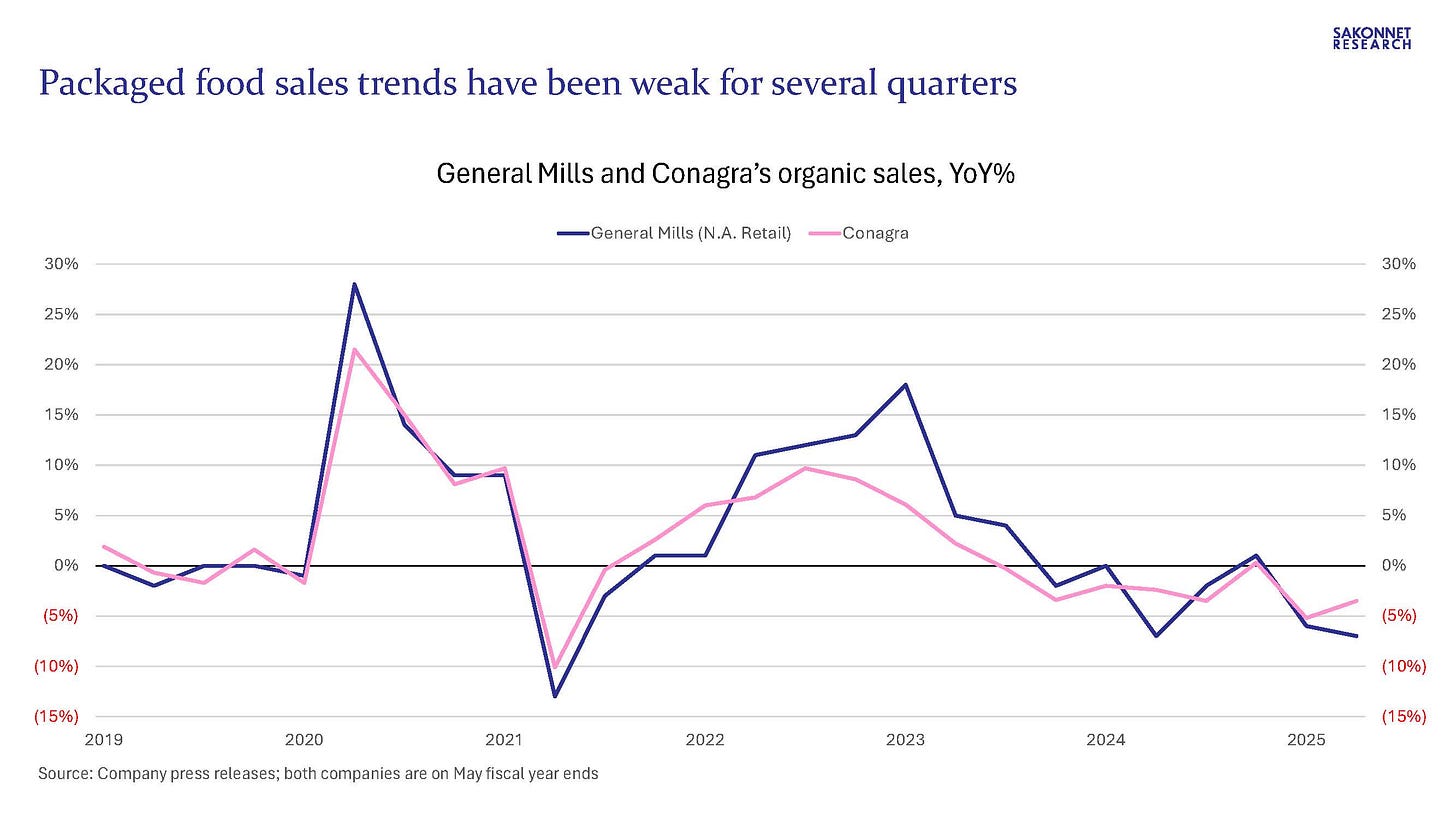

Why has box demand been so weak in recent years, besides the ongoing substitution from boxes to other types of packaging by the likes of Amazon? Existing home sales have been historically low. The ISM manufacturing PMI has been in contraction for 30 of the past 32 months. Consumer packaged goods (CPG) volumes have been in contraction from 2022 onward, and more recently retailers and restaurant chains’ comparable/same-store sales have gone nearly flat based on data from many of the large publicly-traded companies. The Financial Times published an article last weekend about packaged food companies’ many problems (which include Americans’ use of GLP-1 drugs, growing concerns about the health risks of eating ultra-processed foods, and high prices), and new research from the Urban Institute found that the so-called big, beautiful bill includes significant cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps. Lower SNAP benefits will lead to lower grocery spending, all else equal.

The latest evidence of protracted sales weakness among packaged food companies came from two prominent companies this morning. Conagra’s organic sales fell by 3.5% in its quarter ended May (see below); its organic sales have declined in seven of the past eight quarters. And Kellogg announced its preliminary 2Q sales and adjusted EBITDA results in conjunction with its acquisition by Ferrero (link); its net sales were down ~9% vs. a year ago, and its adjusted EBITDA was down ~42%.

Many CPG companies other than packaged food companies are experiencing sales/volume weakness as well. Beer demand is poor, which is evident from Beer Institute and National Beer Wholesalers Association (NBWA) data. Soda makers Coca-Cola and PepsiCo both reported 3% volume declines in North America in 1Q25. The liquor/spirits industry experienced a rare sales decline last year (link). And a number of purveyors of household and personal care (HPC) products reported flat or declining volume in 1Q25.

And as perhaps goes without saying, population trends are important to CPG companies (and many others). The Dallas Fed published a study two days ago that estimated a potential significant hit to GDP growth resulting from reduced unauthorized immigration following a surge in such immigration from 2021 to 2024. Concluded the authors, “Our analysis raises the concern that a sharp tightening of immigration policies has the potential to substantially reduce output growth.”