Will an SLR Reduction Really Help the Treasury Market?

"So you're telling me there's a chance..."

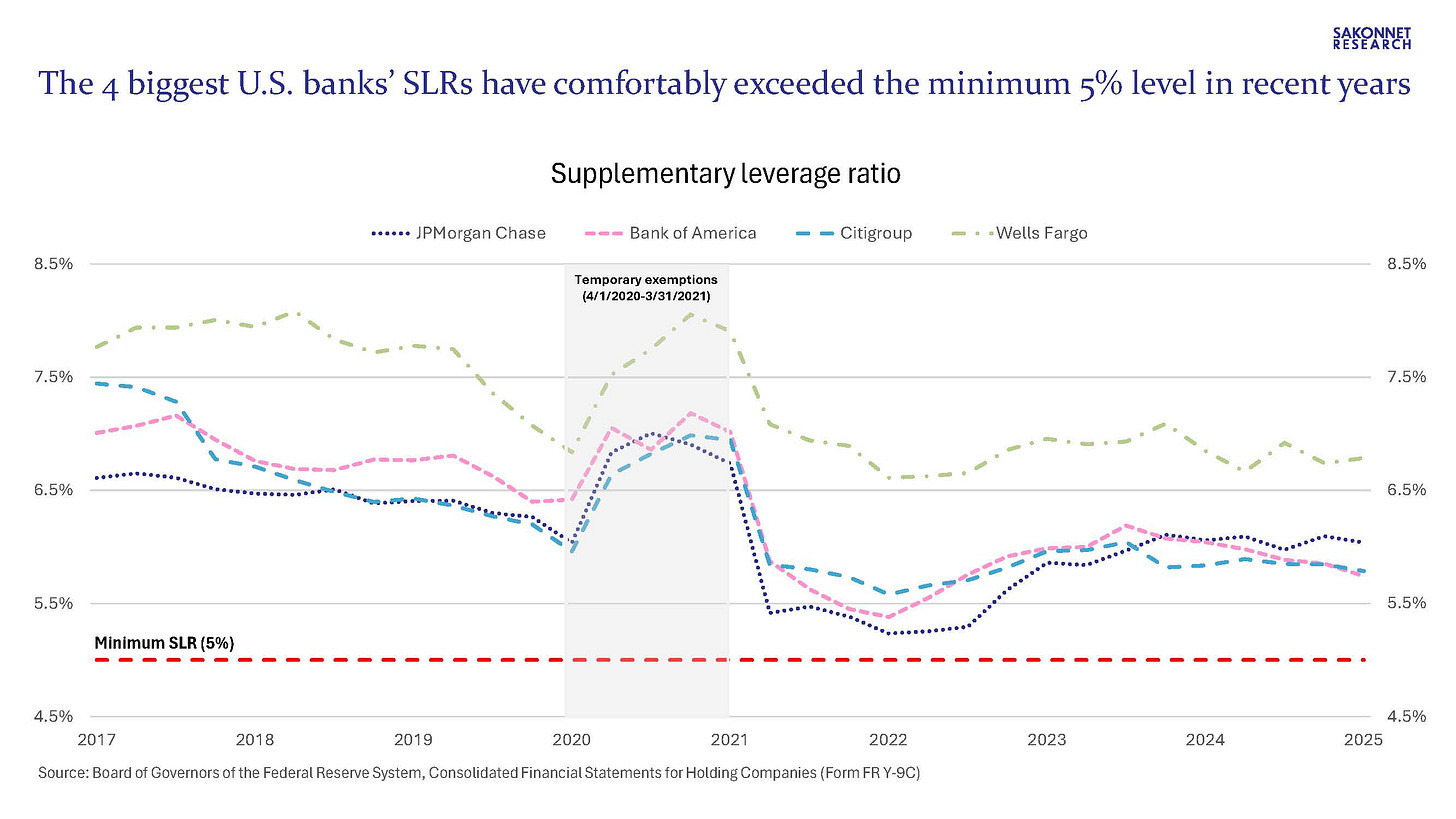

Last week, the Federal Reserve (Fed) announced an open board meeting on Wednesday, June 25 to discuss proposed changes to what’s known as the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR); Bloomberg reported that the Fed and other U.S. bank regulators plan to reduce the SLR, which could have the effect of boosting demand for U.S. Treasury securities. At the risk of scaring off all my readers before I’ve even begun with an alphabet soup of acronyms (!), the SLR is a capital requirement that regulators established in the wake of the 2007-09 Great Financial Crisis (GFC) to prevent excess leverage from building up in the financial system. The SLR measures a banking organization’s Tier 1 capital relative to its total leverage exposure (TLE); TLE includes on-balance sheet assets and certain off-balance sheet exposures such as derivatives and Treasury secured financing transactions (SFTs). All banks must maintain an SLR of at least 3%, but the eight U.S. Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIBs) are required to hold an additional 2%, such that the “enhanced” SLR (eSLR for short) is at least 5%. Per the Bloomberg article, the proposal would reduce the eSLR for large U.S. bank holding companies (BHCs) from 5% to 3.5% to 4.5% and for their bank subsidiaries from the current 6% to the same 3.5% to 4.5% range.

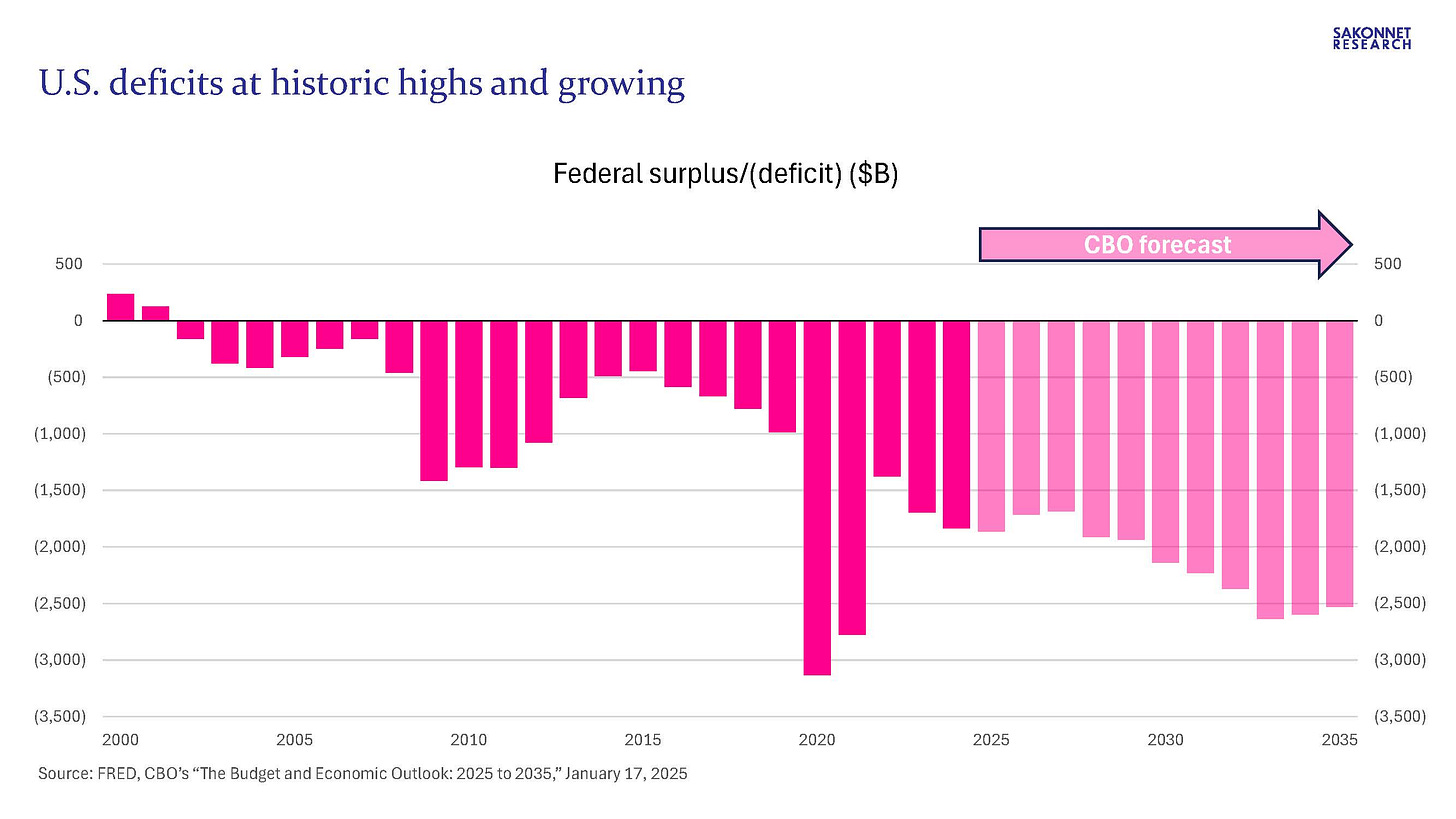

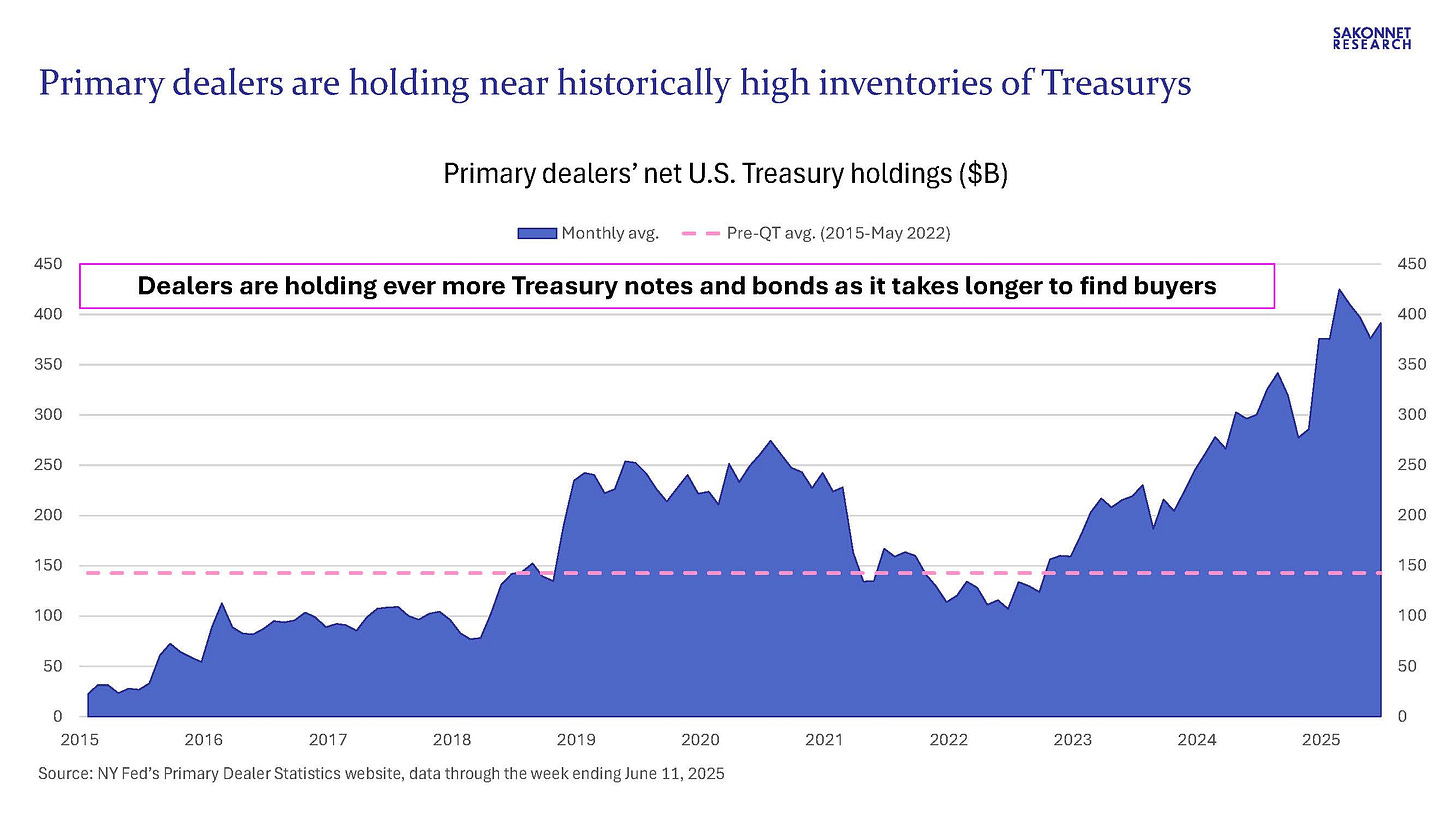

Why are bank regulators reportedly planning to reduce this capital requirement? Fed chair Jerome Powell said in February that he had been “somewhat concerned about the levels of liquidity in the Treasury market,” and primary dealers have claimed the SLR is clogging up the system (link). Per a 2023 FEDS Notes piece, as a non-risk weighted capital requirement, the SLR is particularly affected by high-volume, low-risk activities such as Treasury market intermediation (which is the domain of primary dealers, the six largest of which are affiliated with large U.S. BHCs and account for nearly 80% of total primary dealer assets). Regulators and financial industry participants are concerned about Treasury demand, and understandably so. It’s not just that long-term Treasury yields are at or near the highest levels they’ve been since 2007; it’s also that the supply-demand imbalance looks likely to worsen.

What role do primary dealers play in the Treasury market? As the Bank Policy Institute (BPI) put it earlier this year, “In the Treasury market, dealers serve as important intermediaries, facilitating trades with a broad range of clients, including foreign central banks, asset managers, pension funds and hedge funds. These dealers maintain significant balance sheets to support longer-term positions and larger trades, often warehousing securities when there is no immediate offsetting interest. The role of dealers is especially important in the off-the-run securities market (any Treasury security that has been issued), where their ability to hold positions until matching buyers or sellers emerge is necessary for market functioning.”

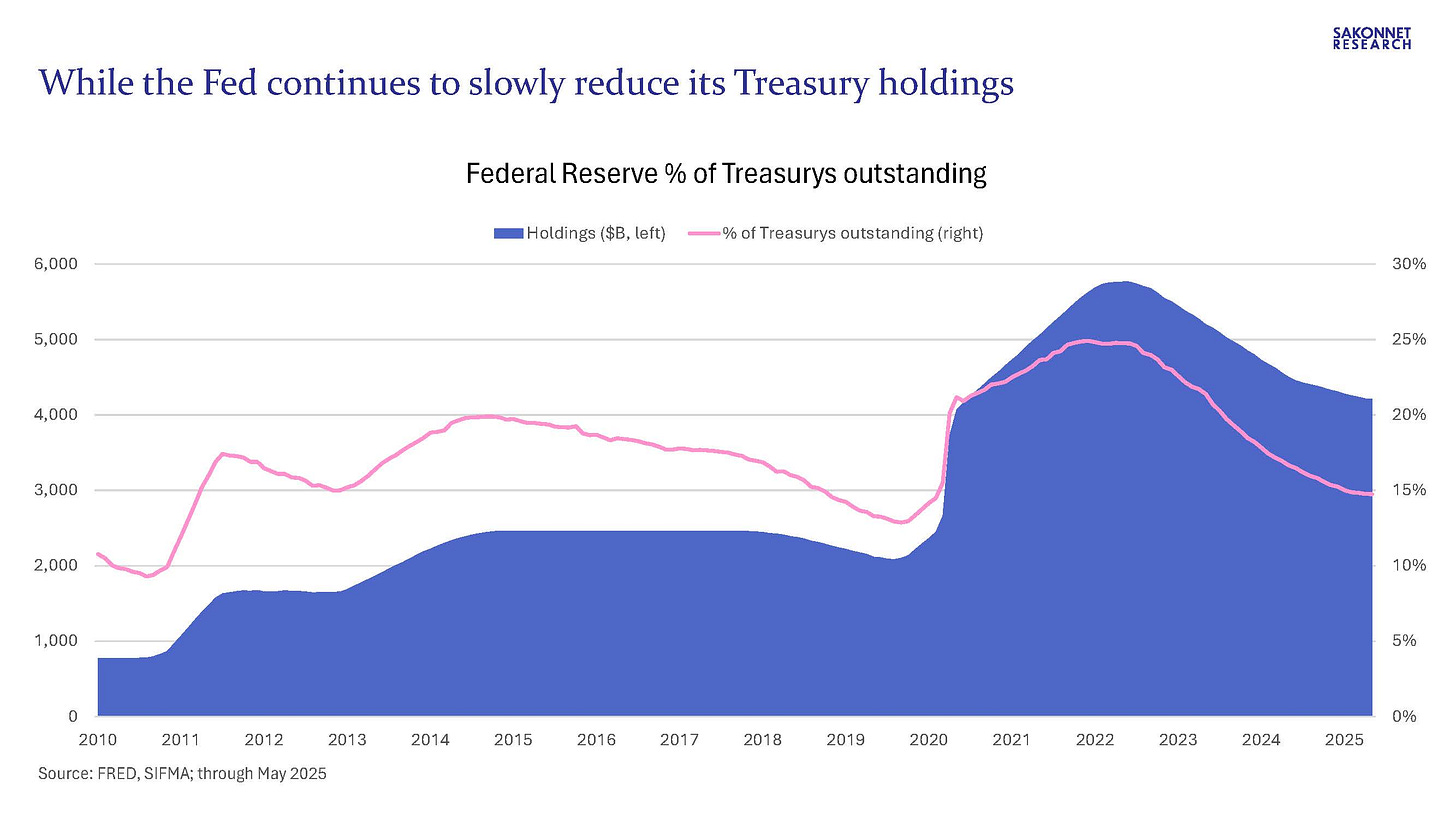

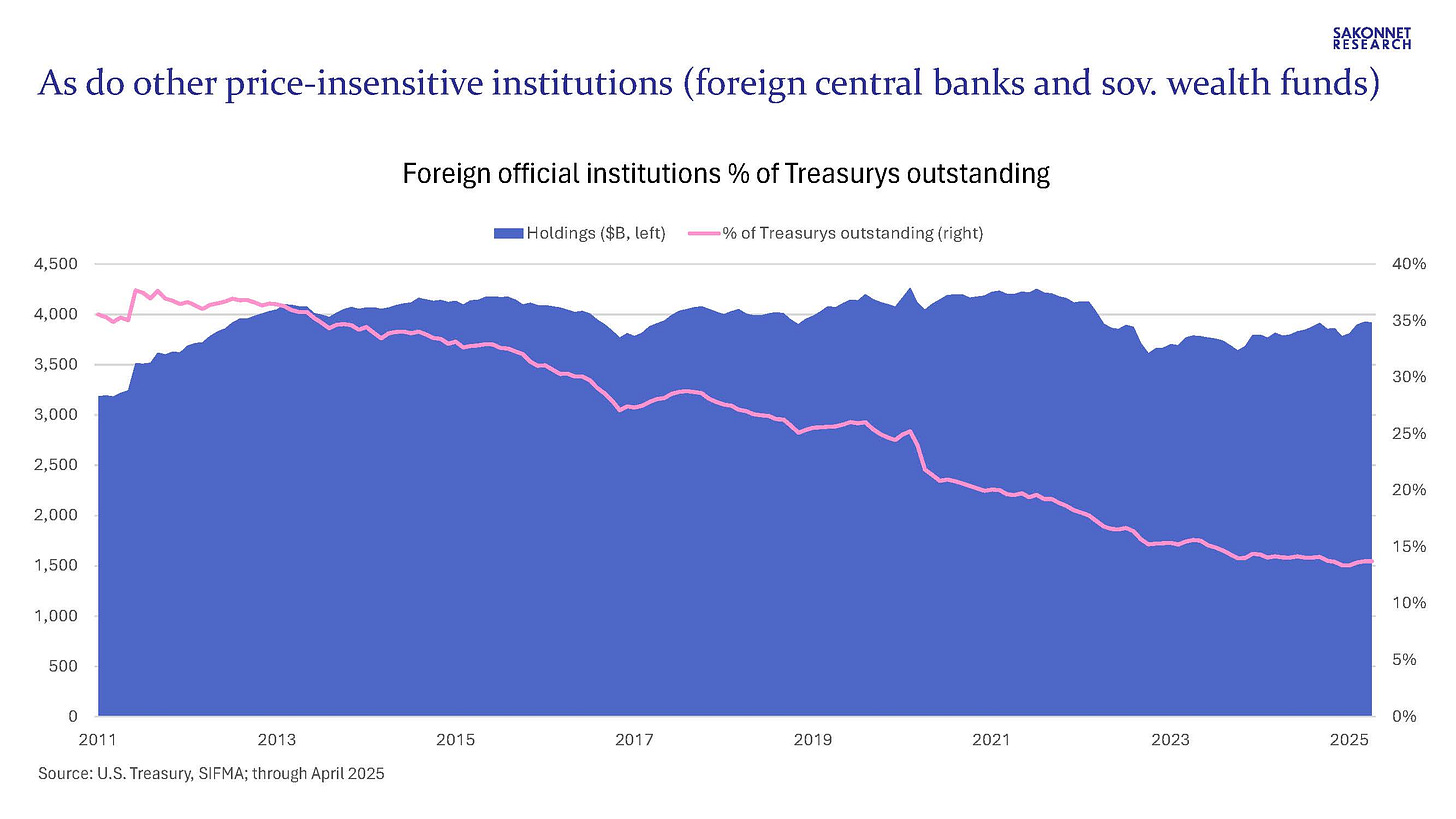

The decline in primary dealers’ intermediation capacity is apparent. They’re holding (“warehousing” in BPI’s terminology) near record-high inventories of Treasurys: $400 billion as of June 11, compared to the all-time high of $455 billion reached at the end of February. Consequently, their share of U.S. Treasurys outstanding is the highest it’s been this century. At the same time, their equity/capital as a percentage of Treasurys outstanding is at a century low. The bulge in dealers’ Treasury inventories has coincided with ever-growing Treasury issuance (the result of historically large fiscal deficits that are projected to get even larger over the coming decade) and declining Treasury ownership among price-insensitive institutions, specifically the Fed via its quantitative tightening (QT) program and foreign official entities such as foreign central banks and sovereign wealth funds.

To the extent these trends (abundant and growing Treasury supply and declining Treasury demand among price-insensitive buyers) continue, it’s unclear what primary dealers will do given how high their inventories already are and low their equity is relative to Treasurys outstanding. After all, dealers are in the business of market making, not holding Treasurys. For those wondering if the Fed will stop QT and revert to quantitative easing (QE) anytime soon as it’s done four times since the GFC, the New York Fed noted on Friday in The Teller Window that global central bank balance sheets “are expected to shrink meaningfully as a share of GDP compared with the recent peak.” And Roberto Perli, the manager of the System Open Market Account (SOMA), said the Fed’s standing repo facility (SRF) will grow in importance as reserve levels decline.

Per a recent blog post from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), almost all primary dealers (21 of the 25) are broker-dealer subsidiaries of large BHCs, including six of the eight U.S. GSIBs. Based on my analysis of primary dealers’ annual FOCUS reports filed with the SEC, the six largest primary dealers (all subsidiaries of large U.S. BHCs) accounted for 76% of total primary dealer assets and 69% of equity last year, highlighting their importance. And there are reasons to think an SLR reduction won’t have much of an effect on them.

FT Alphaville recently pointed out, citing JPMorgan research, that the SLRs of the four largest U.S. BHCs have been above 6% for the past several years (the group average has been 6.1% from 2022 onward) even as the volume of their outstanding preferred stock - the least expensive form of Tier 1 capital - has been on the decline. In other words, the SLR isn’t a binding constraint for them. The aforementioned FEDS Notes piece, which examined the response of the six largest U.S. BHCs and their dealer subsidiaries to the temporary exclusions of reserves and Treasury security holdings from the SLR denominator between April 2020 and March 2021, found no noticeable effect on dealers’ direct holdings of Treasurys or their SFTs backed by Treasurys. (FEDS Notes are written by staff of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.)

If an SLR reduction was to have an impact on large BHCs and their bank and broker-dealer subsidiaries, what would it be? The broker-dealer subsidiaries would become even more levered, and they’re already quite so. Per FOCUS report data, the aforementioned 25 primary dealers have an assets/equity (leverage) ratio of nearly 29 times, up from the low 20s as recently as 2021. For those wondering why the recent substantial increase, the 2021 collapse of Archegos cost its trading counterparties around $10 billion of losses (which reduced their equity): Credit Suisse $5.5 billion, Nomura $2.2 billion, Morgan Stanley $1 billion, UBS $774 million, and Deutsche Bank, Wells Fargo and Goldman Sachs immaterial amounts (link). All were/are primary dealers.

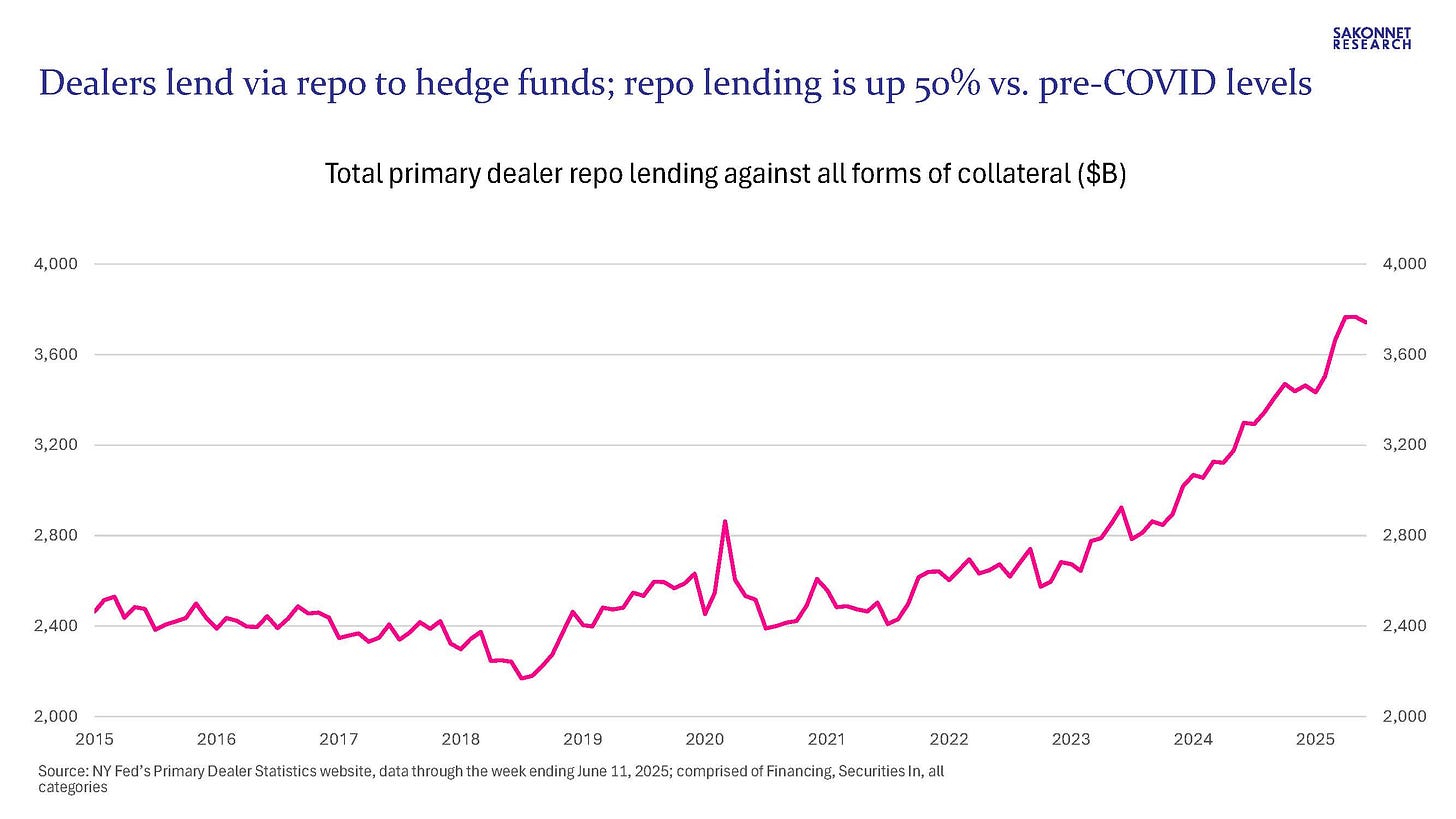

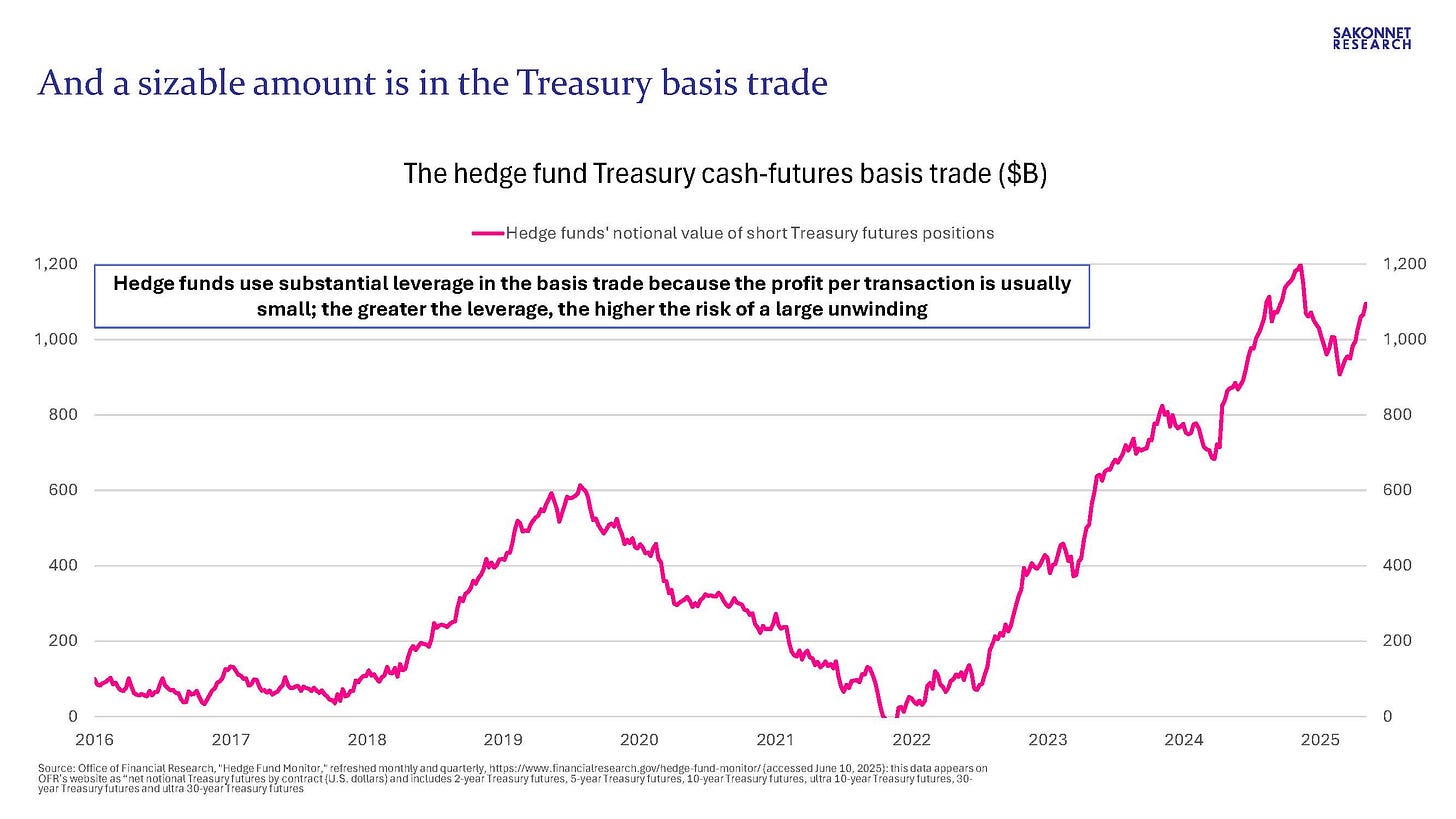

To whom do primary dealers provide leverage? Hedge funds, which are about as levered as they’ve been in recent history (link) and whose borrowing has doubled compared to pre-COVID levels (link). Hedge funds are using this leverage in part to finance the Treasury cash-futures basis trade such that they’ve likely been among the largest Treasury buyers in recent years, but there’s an obvious risk of the trade unwinding, as the Treasury rout following “Liberation Day” highlighted (link). As the Fed noted in its bi-annual Monetary Policy Report published on Friday, “indicators suggest that hedge fund leverage has likely decreased somewhat from historically high levels due to delevering associated with substantial losses on equity and certain relative value trades during April 2025.” Given that hedge fund leverage is at or near historically high levels, why would regulators want to encourage more of it by enabling bank-affiliated broker-dealers to lend them yet more money? Primary dealers’ repo lending against all forms of collateral is already up a dramatic 50% vs. pre-COVID levels after having been flattish for years before the pandemic.