A Predictable Start to 3Q Earnings Season

More sales misses and guidance reductions from consumer-related companies

Last week, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) published its annual update of the National Economic Accounts, which showed better-than-expected real gross domestic product (GDP) and national income growth over the past three years. The bulk of the upward revisions to national income were from corporate profits, proprietors’ income (income from unincorporated businesses), and net interest income. The entirety of the upward revisions to personal income in 2022 and 2023 came from higher personal current transfer receipts (government benefits), higher personal interest and dividend income, and higher proprietors’ income. By contrast, compensation (specifically wages and salaries) was downwardly revised in 2023. Based on the upward revisions to personal income, the personal saving rate (personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income) was revised sharply higher in recent quarters, which suggests that Americans’ ability to spend is greater than previously thought. Real GDP growth of 2.5%-3.0% – which has been the case from 2022 onward – is indicative of a healthy economy, even if government spending has directly and indirectly fueled much of that growth.

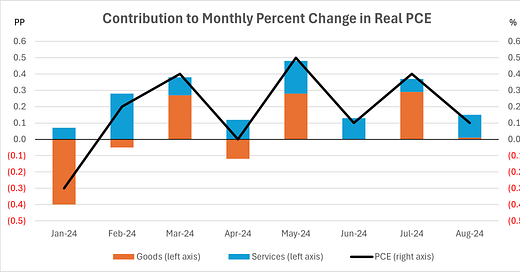

Given the healthy economy, one might assume that companies tied to consumer spending are doing well. After all, consumer spending accounts for nearly 70% of GDP. In many cases, not so. While Costco and Walmart among retailers have continued to perform well thanks to their focus on providing value, the likes of Home Depot, Lowe’s, Macy’s, Best Buy, Williams-Sonoma, Dollar General, Dollar Tree, Nestle, Kraft Heinz, Hershey, Marriott, etc. cut their full-year sales guidance in 2024q2, and the start of third-quarter earnings season has brought more of the same. Thus far, FedEx reported earnings that were 25% below consensus estimates and cut the top end of its full-year earnings guidance; Nike yesterday acknowledged that its sales trends have deteriorated and pulled its full-year guidance; Lamb Weston yesterday cut its full-year profit guidance and announced layoffs (4% of its global workforce) as restaurant traffic and french fry demand remain weak; and Conagra this morning missed consensus on sales and reported a continued deterioration in its organic sales trends (down 3.5% in the August quarter). The consistent theme is that goods spending is stagnant, which was evident in the BEA’s Personal Income and Outlays report for August: goods spending adjusted for inflation was flat, as it was in June. Year to date, services spending has contributed far more to growth in real personal consumption expenditures (PCE) than has goods spending.

For those wondering why services spending has held up as well as it has, housing and utilities accounts for 26%; healthcare 24%; financial services and insurance 11%; food services and accommodations 11%; and everything else 28%. In other words, much of services spending (housing, healthcare, insurance, etc.) is mandatory rather than discretionary, and many of those costs have risen dramatically (think of housing, home insurance and auto insurance) since the pandemic. The more spending on mandatory services, the less spending on discretionary goods.

I expect to see more signs of consumer weakness when the banks start to report next Friday, Oct. 11, in the form of continued increases in charge-off and delinquency rates as well as flattish loans and deposits. CarMax’s provision for credit losses increased by 25% versus a year ago in the quarter it reported last week, and the auto lender Ally Financial warned of intensifying credit deterioration among its borrowers during its appearance at a conference in early September. As I wrote in my last post, I believe banks’ loan growth will remain subdued for the foreseeable future for several reasons: deteriorating credit quality, the Federal Reserve’s ongoing quantitative tightening (QT) program, and signs that some banks are capital-constrained.