How Much is the Fed Doing to Support Treasury Demand?

And how much should it be doing?

Yesterday, the Federal Reserve (Fed), Treasury and others co-hosted their annual conference on the U.S. Treasury market (link). The day before, Bloomberg reported (link) that U.S. bank regulators including the Fed have agreed on the terms to reduce banks’ capital requirements, specifically the so-called enhanced supplementary leverage ratio (eSLR) that applies to the eight U.S. global systemically important banks (“G-SIBs”). Were the rule change to take effect, these banks would be required to hold less capital against their total assets. The proposed eSLR reduction appears to have much to do with the Treasury market, which prompted me to wonder how much support the Fed is trying to provide Treasury with at a time of historically large and growing budget deficits and declining Treasury demand among foreign central banks. As Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said yesterday, “Treasuries are not only the bedrock of the global financial system but also the American Dream. Treasury yields have a trickle-down effect on the broader economy that determines whether a young family can afford a home, a college student can buy a car, or an entrepreneur can get a small business loan.” More from him later.

Per the Bloomberg article:

Michelle Bowman, the Fed’s vice chair for supervision, said in June that the planned changes would help build resilience in Treasury markets and reduce the need for the Fed to intervene in a future stress event.

In other words, the Fed and other regulators appear to be hoping to boost demand for U.S. Treasurys—which would have the effect of reducing the government’s interest costs—by reducing large banks’ capital requirements. The Fed is apparently prepared to go ahead with this plan even though its own study in 2023 (link) concluded that the SLR had no discernible impact on the ability of bank-affiliated primary dealers to intermediate in Treasury markets. As Fed Governor Michael Barr, who previously served as the Fed’s vice chair for supervision and who objected to this plan, said:

Enhancing the resilience of the U.S. Treasury market is an important objective that I share with my colleagues, but this proposal unnecessarily and significantly reduces bank-level capital by $210 billion for global systemically important banking organizations (GSIBs) and weakens the eSLR as a backstop. I am skeptical that it will achieve the stated objective of improving the resiliency of the Treasury market.

Furthermore, the big banks comfortably passed the Fed’s easier annual stress test in June, following which four of them substantially increased their stock buybacks compared to a year ago (link). Buybacks and dividends reduce banks’ capital, which is why the Fed froze buybacks and capped dividends for the largest ones in 2020.

So, what’s the Fed hoping to accomplish by further loosening banks’ capital requirements, particularly amid a deteriorating economy and recent high-profile credit blowups? As Fed Chair Jerome Powell said in June (link):

We also have seen Treasury holdings in the banking system climb precipitously. This stark increase in the amount of relatively safe and low-risk assets on bank balance sheets over the past decade or so has resulted in the leverage ratio becoming more binding. Based on this experience, it is prudent for us to reconsider our original approach. Because banks play an essential intermediation role in the Treasury market, we want to ensure that the leverage ratio does not become regularly binding and discourage banks from participating in low-risk activities, such as Treasury market intermediation.

The “stark increase” in banks’ Treasury holdings to which he referred is the result of several factors: (1) post-Great Financial Crisis (GFC) regulations that incentivized banks to hold more liquid assets; (2) regulations that assign Treasurys a 0% risk weight, treating them as equivalent to cash and thereby making them more attractive for banks to hold; and (3) the large amount of Treasury issuance over the past decade stemming from persistent and growing budget deficits (Treasurys outstanding have grown at a CAGR of 8.5% over the past decade, dwarfing GDP growth during that period).

In other words, the Fed is hoping to address a perceived problem that its own regulations are partly responsible for, that’s emanating from profligate government spending, and that its own researchers determined likely wouldn’t be solved by lowering the SLR. Two out of seven Fed governors voted against putting the proposal out for public comment. As Sheila Bair, former chair of the FDIC, wrote in the Financial Times in July (link), “The regulator’s job is to ensure the safety and stability of the financial system, not help the government fund its deficits.”

Now I’ll turn to yesterday’s Treasury conference. One of the topics discussed was the repurchase agreement (repo) market, which hedge funds use to finance their (levered) Treasury purchases. The repo market is where broker-dealers and hedge funds borrow from money market funds (MMFs) and banks to finance their securities purchases (including U.S. Treasurys), and recent developments in that market prompted the Fed to stop its quantitative tightening (QT)/balance sheet reduction program effective December 1.

Rising repo rates mean higher securities financing costs, making it more expensive for hedge funds to speculate on financial assets using leverage. And that’s precisely what hedge funds have been doing ever more of post-COVID: hedge fund leverage is at record highs (link), much of which has recently gone toward financing the 50-100x leveraged Treasury cash-futures basis trade.

According to a recent Fed paper (link), Cayman Islands hedge funds absorbed an estimated 37% of net Treasury note and bond (not bill) issuance from 2022 to 2024, and their estimated $1.85 trillion of Treasury holdings at the end of 2024 dwarfed what was reflected in the official U.S. Treasury International Capital (TIC) data and what China, Japan and the United Kingdom each hold. As repo rates rise, the cost of putting on this highly leveraged trade goes up accordingly, bearing in mind that the profit per trade is small to begin with (thus the amount of leverage used to make the trade worthwhile). A less profitable trade could lead to less hedge fund Treasury buying, or even outright sales.

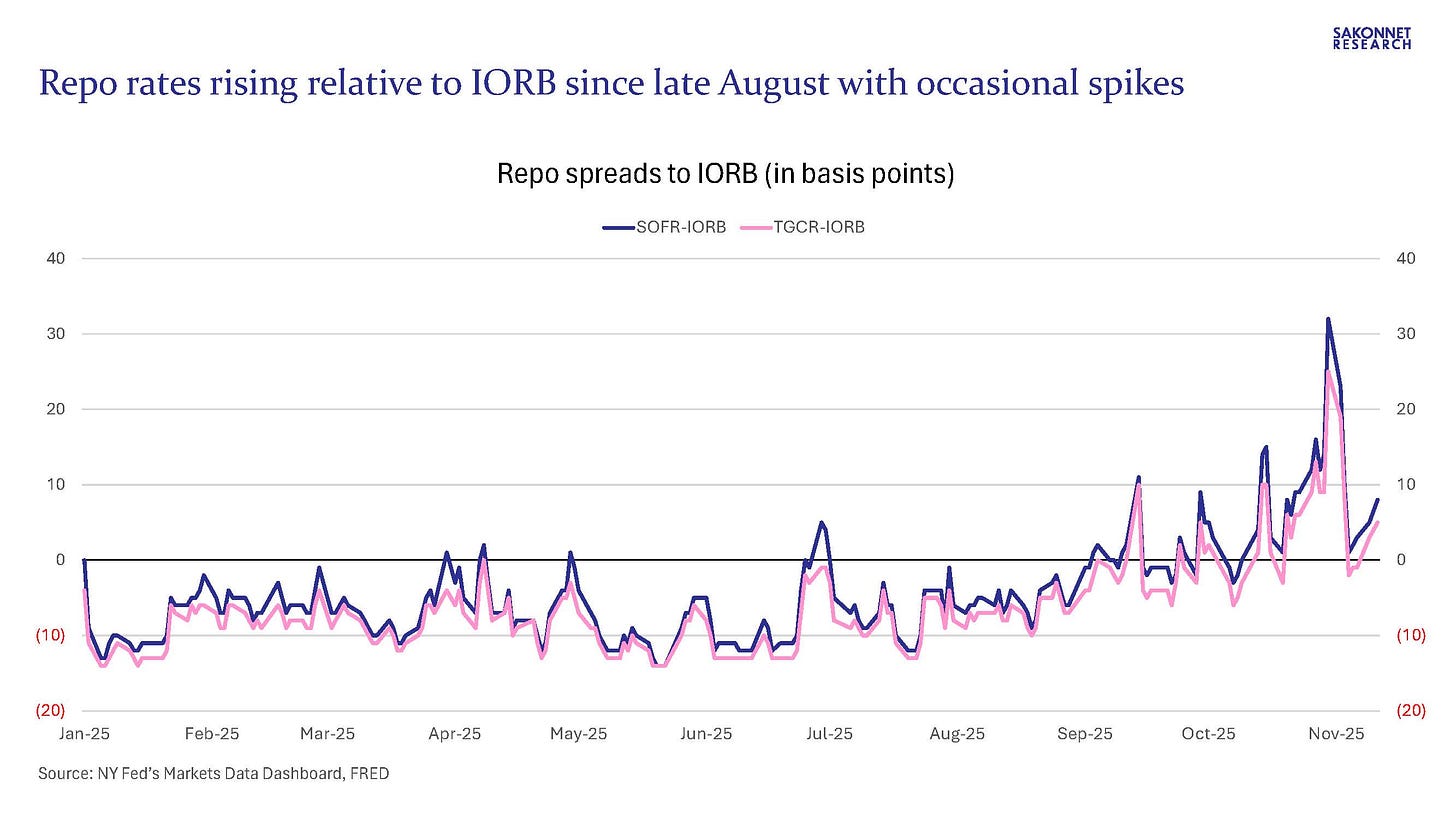

The Fed has observed the recent rise in repo rates relative to the interest on reserve balances (IORB) rate and spikes in repo rates at month- and quarter-ends, thus the end of QT.

To prevent such spikes in repo rates from lasting long, the Fed introduced the standing repo facility (SRF) in 2021. As NY Fed President John Williams said at the conference (link), the SRF has been effective, having experienced a higher volume of take-up especially on days of temporary repo market pressures (typically though not always month- and quarter-ends). He expects market participants to continue to “actively” use the SRF in this way and that the SRF will “contain upward pressures on money market rates.”

Roberto Perli, who runs the System Open Market Account (SOMA) at the NY Fed, said much the same (link):

And even as of now, if repo pressure persisted, or intensified, I do expect that the SRF will be used more broadly and to a much larger extent, thus dampening the upward rate pressure…The SRF is an essential part of our toolkit that supports the effective implementation of monetary policy and smooth market functioning, thereby helping us achieve strong rate control…Our counterparties participated in large scale in the repo operations that the Federal Reserve offered in the past; if it makes economic sense, there is no reason why sizeable participation cannot take place now that repo operations are offered twice daily on a standing basis.

Growing dealer take-up of the SRF would technically expand the Fed’s balance sheet (a loan is an asset just as a security is), but in a much different way than asset purchases. As Mr. Williams noted, the SRF rate is set at the top of the FOMC’s target range for the federal funds rate, which reduces the day-to-day reliance on it except during periods of market stress.

The existence of the SRF, and of the discount window facility, won’t necessarily preclude the Fed from resorting to large-scale asset purchases again in the next crisis. That said, Fed officials expect much greater usage of the SRF in the foreseeable future, and banks had prepositioned nearly $3 trillion of collateral at the discount window by year-end 2023 at the Fed’s urging following the March 2023 banking crisis. In other words, the Fed’s response to the next crisis could look much different than its responses to crises from the GFC onward.

I wrote earlier that rising repo rates could make the basis trade less profitable, and that Cayman Islands hedge funds putting on this trade are estimated to have absorbed an enormous share of net Treasury note and bond (not bill) issuance from 2022 to 2024. Bills have short-term maturities while notes and bonds have medium- and long-term maturities, respectively. The bill vs. note and bond distinction is an important one.

Along those lines, Mr. Bessent said at the same conference (link) that the Fed will start to buy Treasury bills with the proceeds from its mortgage-backed securities (MBS) holdings, and that he’s (unsurprisingly) supportive of the potential eSLR reduction. “Since the start of this year, bank portfolios have expanded their Treasury holdings. Additional reforms, including the potential eSLR reform I mentioned earlier, could further accelerate this process.” To his point about banks’ Treasury holdings, they’ve gone from $1.42 trillion at the end of 3Q24 to $1.61 trillion a year later per call report data from BankRegData, and JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America each hold over 1% of total Treasurys outstanding (U.S. banks hold 5.5% of Treasurys outstanding).

Where else is he seeing growing demand for Treasury debt? Money market funds (MMFs) and stablecoin providers are buying more bills (I wrote about MMFs’ bill demand here), but no mention of any entities that are buying more notes and bonds (meaning taking on duration risk). As noted earlier, the Fed will start buying bills too.

But what about longer-duration Treasurys? That’s where the highly leveraged Cayman Islands hedge funds have played an important role in recent years. Mr. Bessent noted that foreign investors’ Treasury holdings are at record levels, but not that foreign central banks (“foreign officials” in the TIC data) have reduced their holdings over the past decade (link). In other words, it’s rate-sensitive foreign private sector buyers that have picked up the slack, including Cayman Islands hedge funds putting on the basis trade. It’s those buyers that are largely financed in the repo market and whose borrowing costs are rising. But even Cayman Islands hedge funds can only buy so many notes and bonds and therein lies Treasury’s problem.

Consequently, after having repeatedly criticized his predecessor for relying too heavily on short-term bill issuance to fund the deficit, Mr. Bessent has employed the same strategy that she did (link). Treasury indicated in last week’s quarterly refunding announcement (link) that it had no plans to change note and bond auction sizes for “at least the next several quarters.” As Bloomberg noted, market participants have indicated that if Treasury keeps relying on bills to fund the government’s large and growing deficits, rollover risk will become ever greater “as massive amounts of bills keep coming due.” If that scenario comes to pass, repo market pressures could become more acute, which begs the question of how the Fed would react.

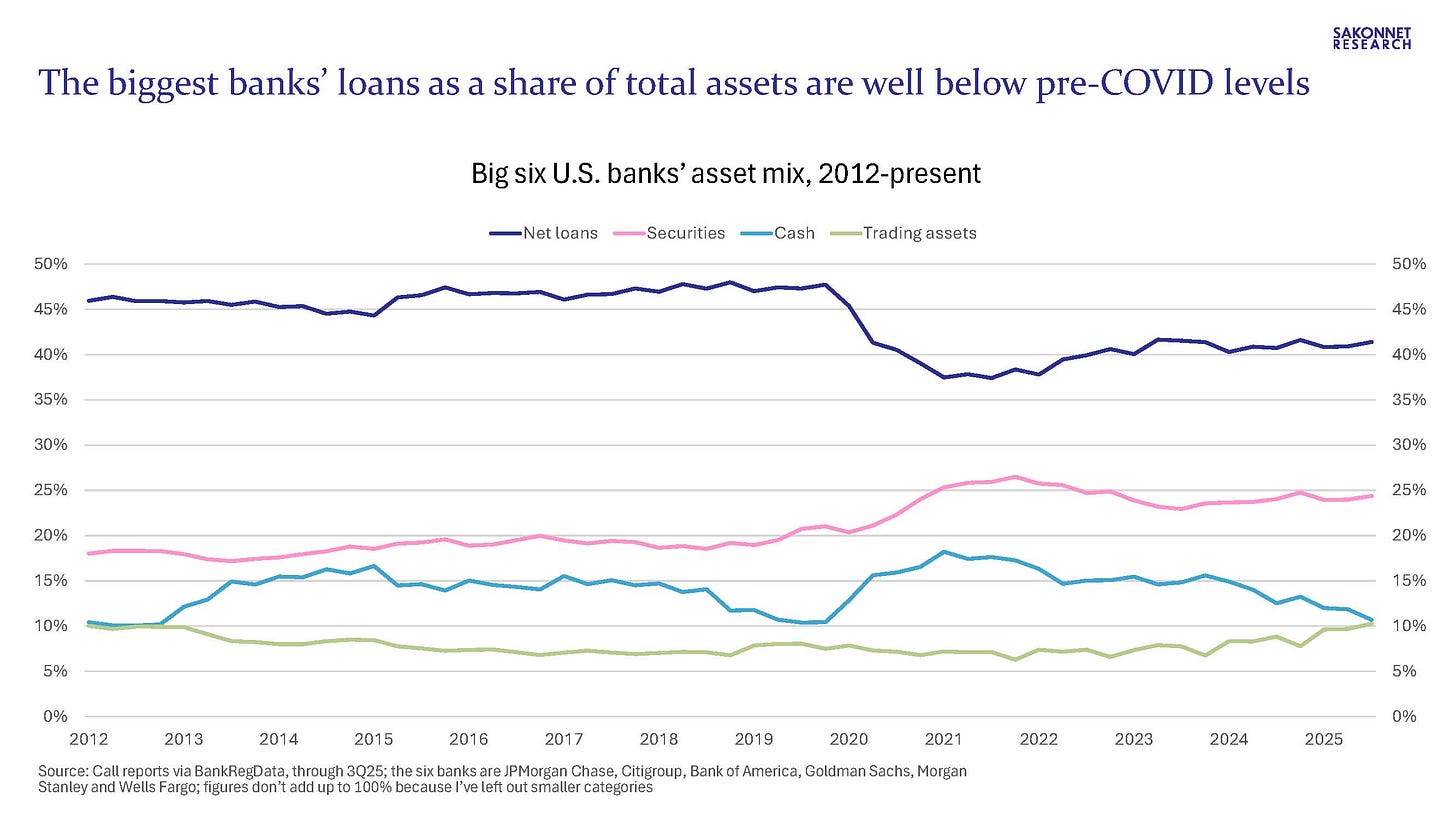

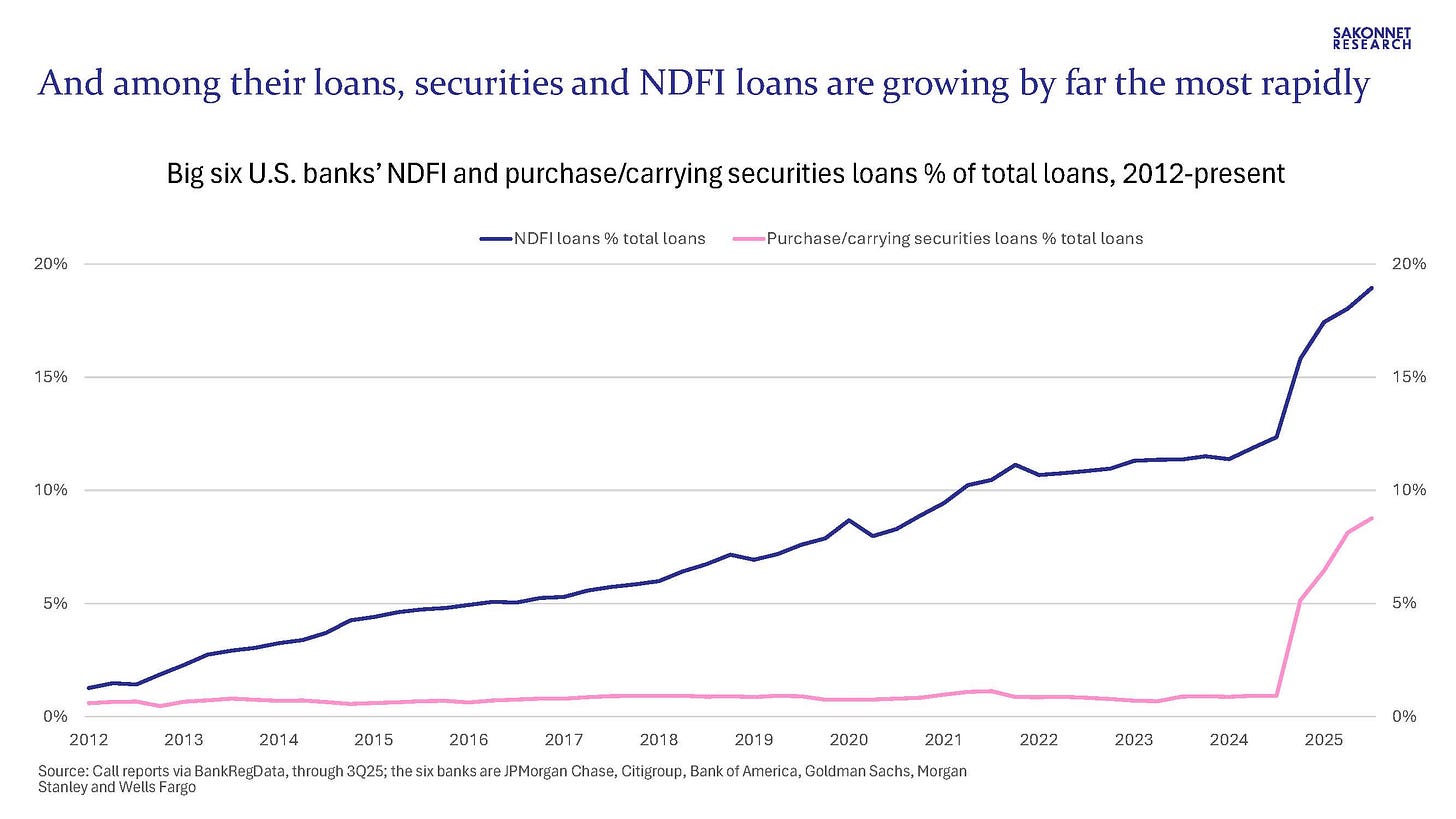

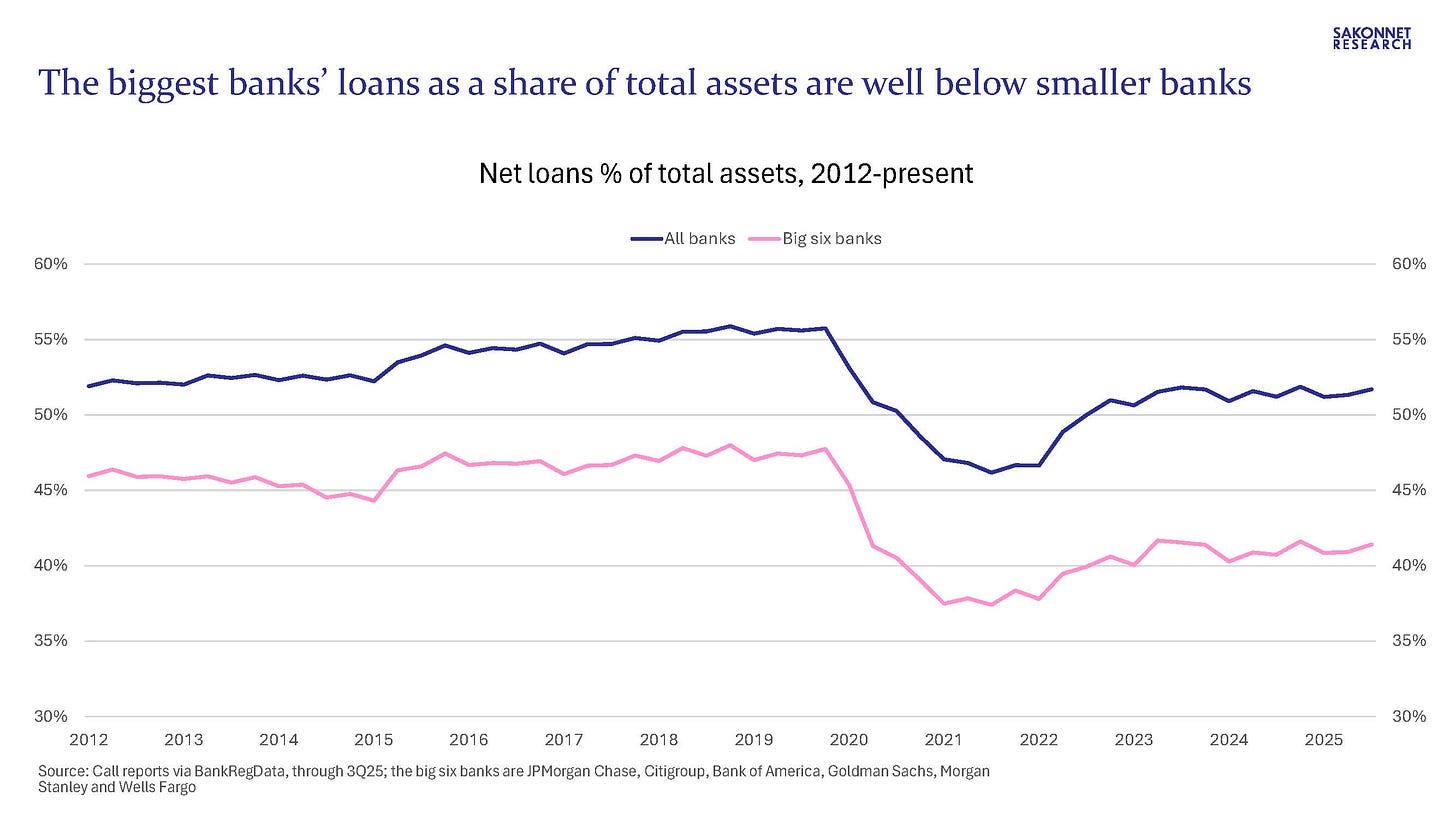

Given the Fed’s push to make it easier for the eight U.S. G-SIBs to play an even more active role in the financial sector (by buying more Treasurys), I thought it appropriate to highlight their asset mix, how it’s changed over time, and how it compares to smaller banks. Among the big six banks (I’ve excluded the two custodian banks that are G-SIBs), loans as a share of total assets are well below pre-COVID levels, while securities holdings and trading assets have risen. Furthermore, among their loans, a rapidly growing share have been securities and nondepository financial institutions (NDFI) loans. In other words, an ever-higher share of the biggest banks’ assets has gone to the financial sector at the expense of the real economy. It should come as no surprise, then, that the real economy is limping along while the financial sector (as evidenced by booming asset prices) is flourishing.

The content in As the Consumer Turns newsletters should not be construed as investment advice offered by Adam Josephson. This market commentary is for informational purposes only and is not meant to constitute a recommendation of any particular investment, security, portfolio of securities, transaction or investment strategy. The views expressed in this commentary should not be taken as advice to buy, sell or hold any security. To the extent any content published as part of this commentary may be deemed to be investment advice, such information isn’t tailored to the investment needs of any particular person. No chart or graph provided should be used to determine which securities to buy or sell.