My last post was about the SLR (and touched on TLE, SFTs, GSIBs, BHCs, QE and QT); this one’s about NDFIs. Fortunately there’s a seemingly endless number of (fascinating) banking industry acronyms to write about!

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS), a forum for the world’s central banks, just published its 2025 Annual Economic Report. Per the BIS’s General Manager (link), the “repeated cycle of announcements, adjustments and reversals” of U.S. tariffs and related turbulence has “exposed and amplified long-standing vulnerabilities in the global economy,” including “structurally low economic growth, unsustainable fiscal positions amid historically high public debt and the growing footprint of less regulated non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs).” He noted that the global financial system has undergone major changes in recent years, with two in particular standing out: the growing share of borrowing by governments vs. the private sector following the 2007-09 Great Financial Crisis (GFC), and the shift in the source of funding from banks to NBFIs.

There are numerous risks associated with the rapid growth of NBFIs (also known as NDFIs).

NDFIs are less transparent and regulated than are banks. An example are private credit firms, which are providing a growing share of financing to small, highly indebted companies. Another are hedge funds, which are funding a growing share of government borrowing, “but often with financial engineering that can be fragile…their complex leveraged positions are vulnerable to adverse shocks, as we have seen in recent years and will likely see again.” He warned that “this deterioration in market function has increased the likelihood of financial stress episodes triggering central bank intervention [emphasis added].”

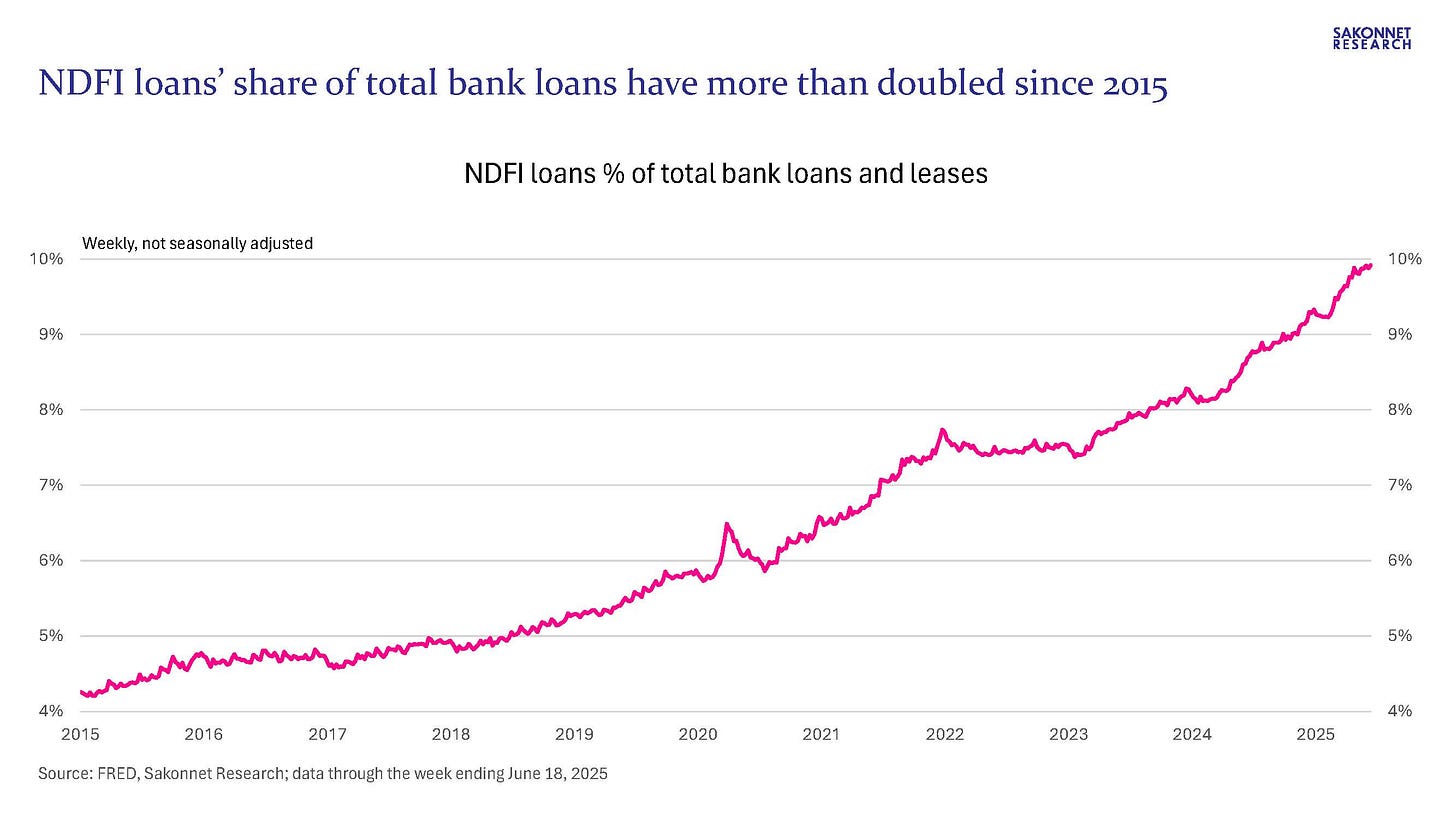

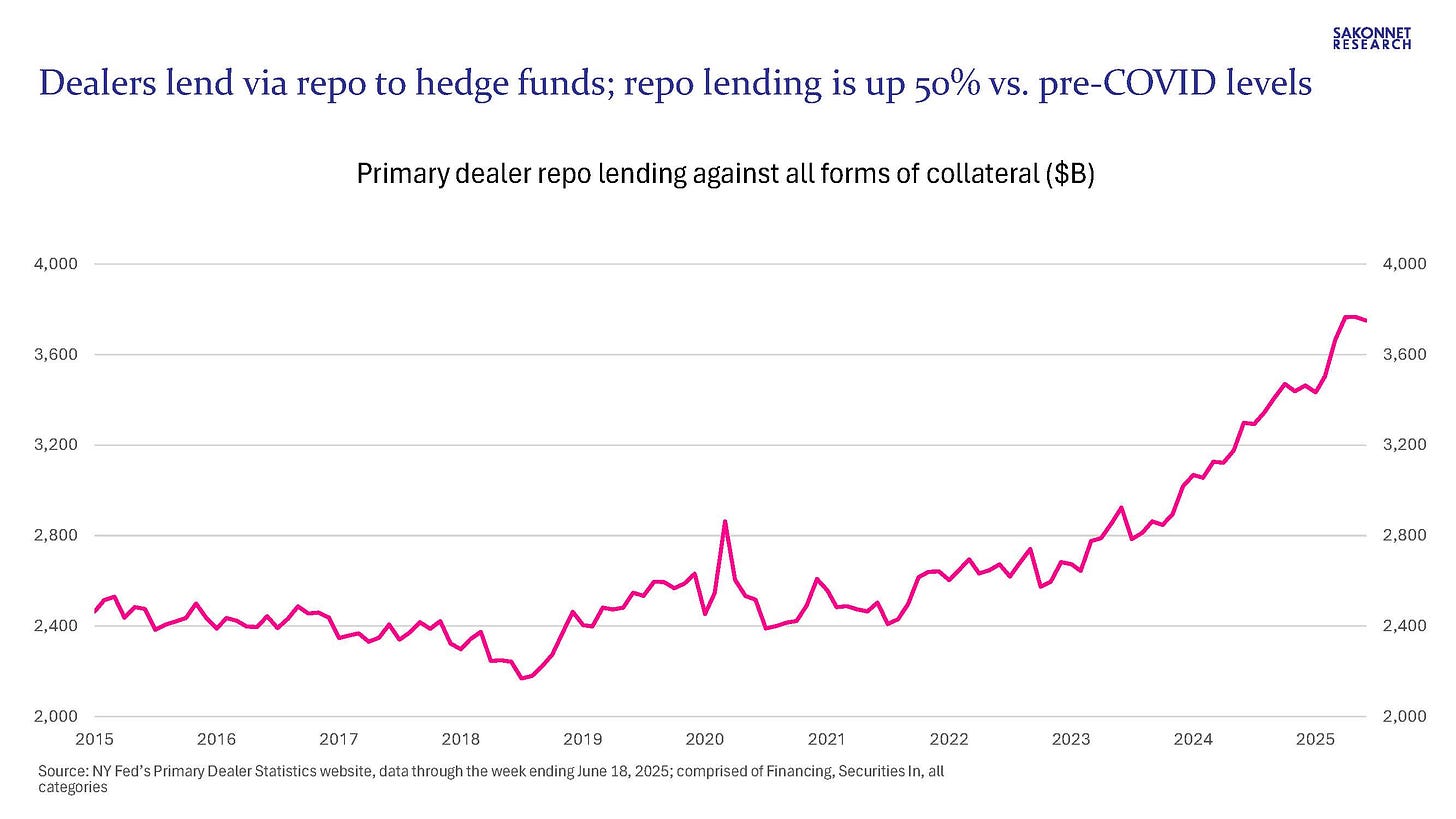

He pointed out the growing heft of NDFIs vs. banks but also noted that banks fund NDFIs in several ways, from providing private credit funds with subscription lines to providing hedge funds with credit lines to collaborating in the securitization of leveraged loans. In other words, banks and NDFIs are interdependent. A critical part of this ecosystem is broker-dealers, the largest of which are affiliated with banks and which lend heavily to hedge funds via repurchase agreements (repo) and other types of secured financing.

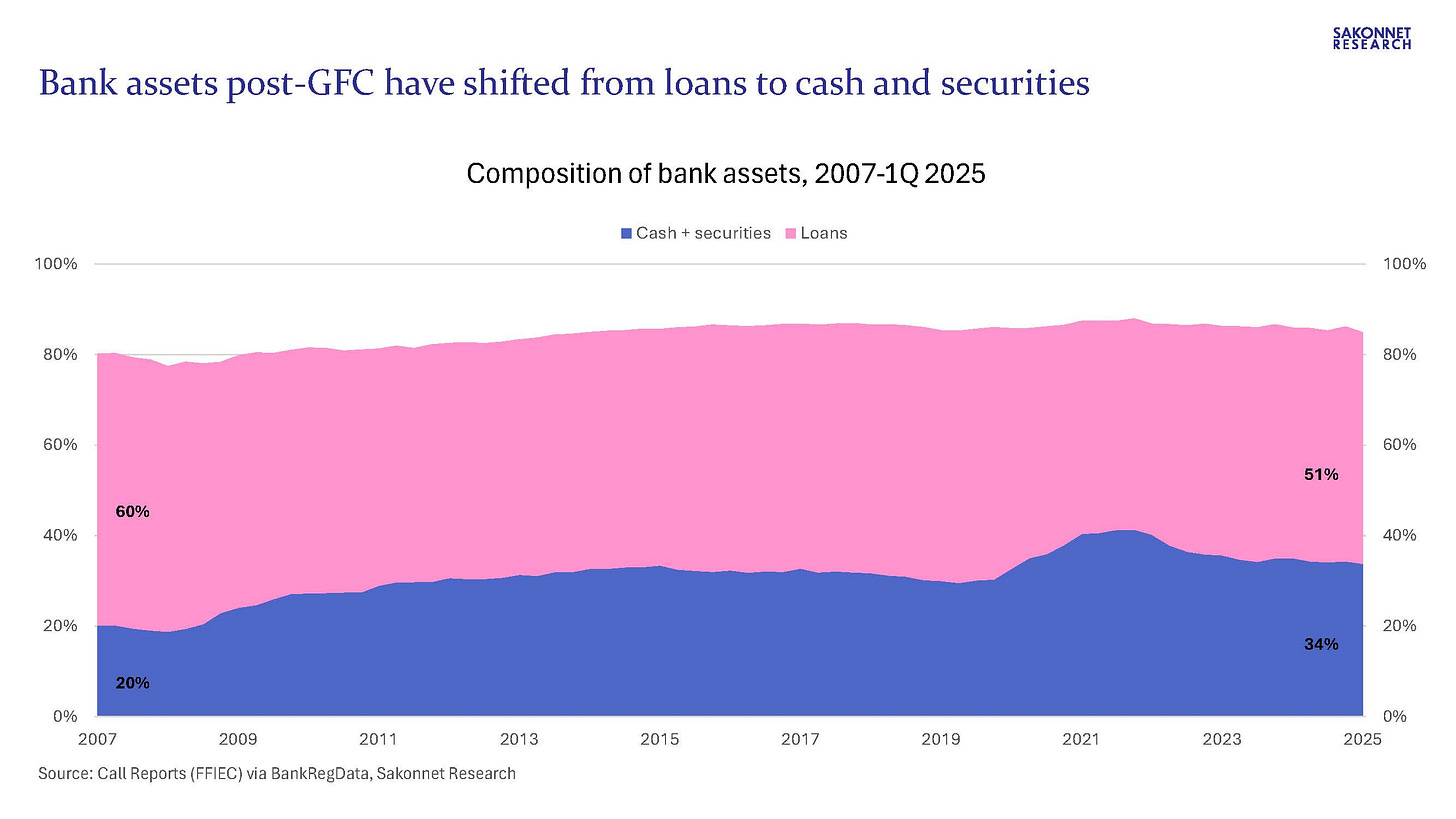

What often goes unexplained is why there’s been such a substantial shift in funding from banks to NDFIs. The banks themselves have facilitated that movement, as the BIS indicated. Bank lending to NDFIs has mushroomed post-GFC, as tighter regulations in the wake of the crisis led to a shift among banks away from lending to businesses and households and toward lending to NDFIs (because of regulatory arbitrage) and holding more cash and securities (because of short-term liquidity requirements). Nicola Cetorelli of the New York Fed pointed out in a presentation at the Atlanta Fed’s recent Financial Markets Conference that the cost of equity for a bank to add a unit of risky loan is high because of regulatory and supervisory costs, and that the same unit of activity done by NDFIs has a higher return on equity because of the absence of regulatory costs. In a slide titled “Deja Vu All Over Again?,” he noted that banks are the funding/liquidity providers to NDFIs, and that the risks ultimately return to banks.

How high is the cost of equity for a bank to make a “risky” loan vs. other types of loans with lower regulatory risk weights attached to them? It’s difficult to find good information on the risk weights associated with different types of bank loans (those to NDFIs vs. corporates, for instance). That said, per the BIS’s standardized approach for credit risk (link), exposures to securities firms under certain conditions are treated as exposures to banks, which have much lower risk weights than do exposures to corporates. In other words, a loan to a bank-affiliated broker-dealer likely has a much lower risk weight than does a loan to a corporate, giving banks an incentive to prioritize NDFIs such as broker-dealers over other types of customers.

Banks lend to NDFIs, and NDFIs such as broker-dealers and private credit firms lend to hedge funds, small and highly indebted corporates, etc. And banks hold more cash and securities than they used to because of post-GFC liquidity requirements. Is it any wonder that banks’ share of nonfinancial corporate borrowing has been on steady decline in recent years, and that the financial sector has grown so rapidly over the same period?

The two most consequential changes in the global financial system that the BIS pointed out — the growing share of credit going to governments and the funding shift from banks to NDFIs — are intertwined. How? Banks, via their affiliated broker-dealers, are lending heavily to hedge funds, which in turn “have become key providers of procyclical liquidity in government bond markets, often employing highly leveraged relative value trading strategies” per the BIS’s Annual Economic Report. “The increased heft of hedge funds is reflected, for instance, in their growing US Treasury gross exposure — now exceeding 10% of the outstanding free float — and the expansion of the US repo market segment catering to leveraged investors.”

As the BIS noted, these strategies are vulnerable to adverse shocks in funding, cash or derivatives markets, and the vulnerability has increased as financing terms have become ever more lax. “Haircuts have gone to zero or even negative in large sections of the repo market, meaning that creditors have stopped imposing any meaningful restraint on hedge fund leverage [emphasis added].”

Negative haircuts are not normal. Indeed, the European Central Bank (ECB) published a paper yesterday that noted the “surprising” prevalence of zero and even negative haircuts, even for riskier collateral, particularly in euro-denominated trades. A haircut means that a lender (in this case a broker-dealer) will lend less than the market value of the pledged security, to protect them from the risk of any loss in value during the time it takes to sell the collateral in the event the borrower (in this case a hedge fund) fails to repay the loan. A negative haircut means the hedge fund is posting collateral worth less than the cash received, such that the broker-dealer is providing that much more leverage.

The lack of any meaningful restraint on hedge fund leverage is consistent with the Federal Reserve’s reporting in recent months that hedge fund leverage was at or near historically high levels. It also begs an obvious question: if broker-dealers are lending this liberally to hedge funds via repo (I noted in my last post that primary dealers’ repo lending is up 50% vs. pre-COVID levels after having been flat for several years beforehand), how vulnerable are all types of asset classes to a sharp downturn? Per the BIS, “This higher leverage leaves the broader market more vulnerable to disruptions, as even slight increases in haircuts can trigger forced selling and amplify financial instability. Such adverse dynamics were on display, for example, during the market turmoil of March 2020, and contributed to the volatility spike in Treasury markets in early April 2025.”

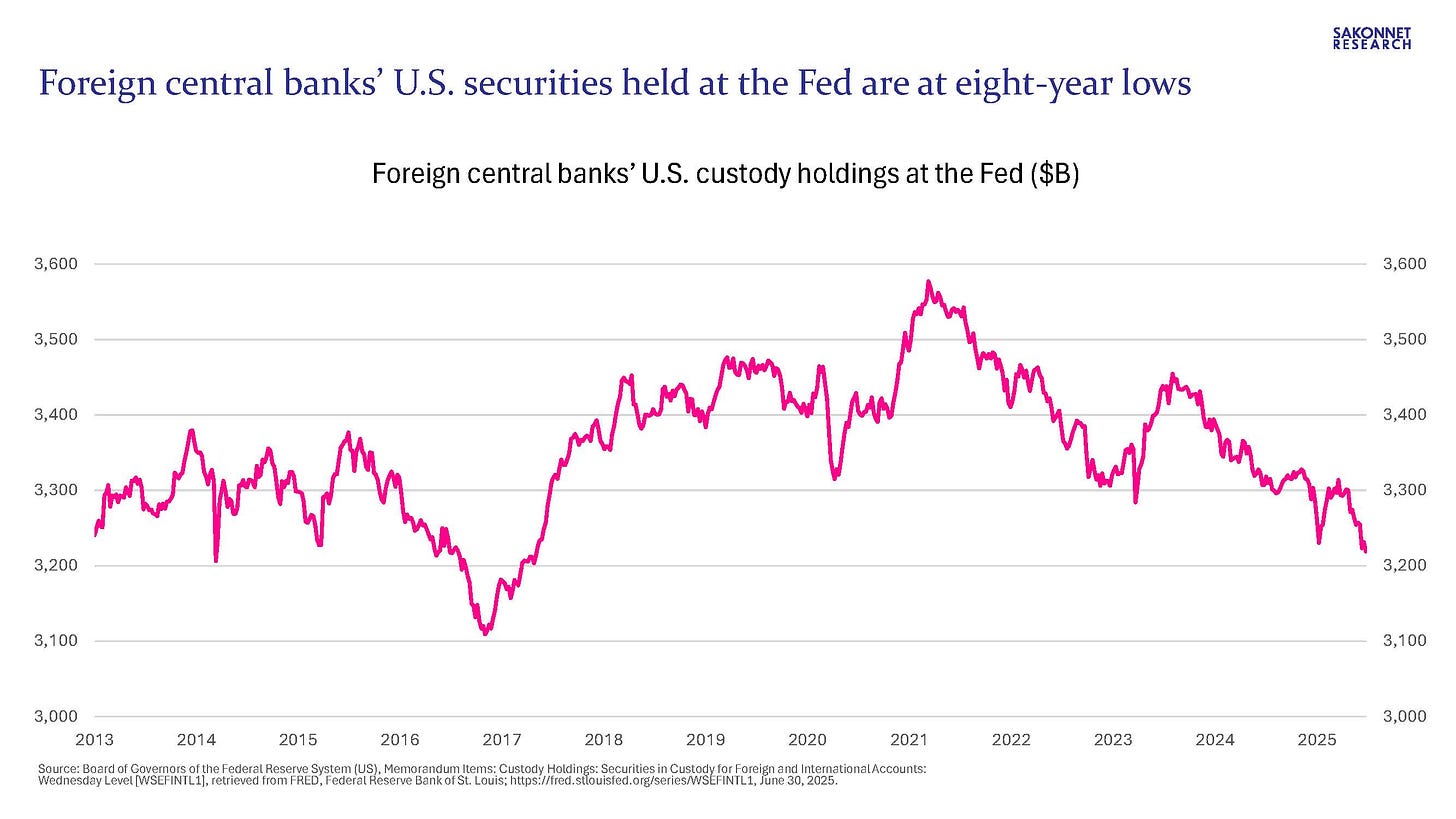

As U.S. government deficits remain historically large (and are projected to grow even larger), who will finance them other than hedge funds, and more to the point at what cost? As the BIS noted, “In the US Treasuries market, the largest bond market in the world, foreign private sector lenders (mainly NBFIs) have increased their holdings of Treasuries rapidly over the past decade. During that time, their accumulation of Treasuries has considerably outpaced that of foreign official holders. As a result, they currently account for more than half of all foreign holdings of Treasuries.”

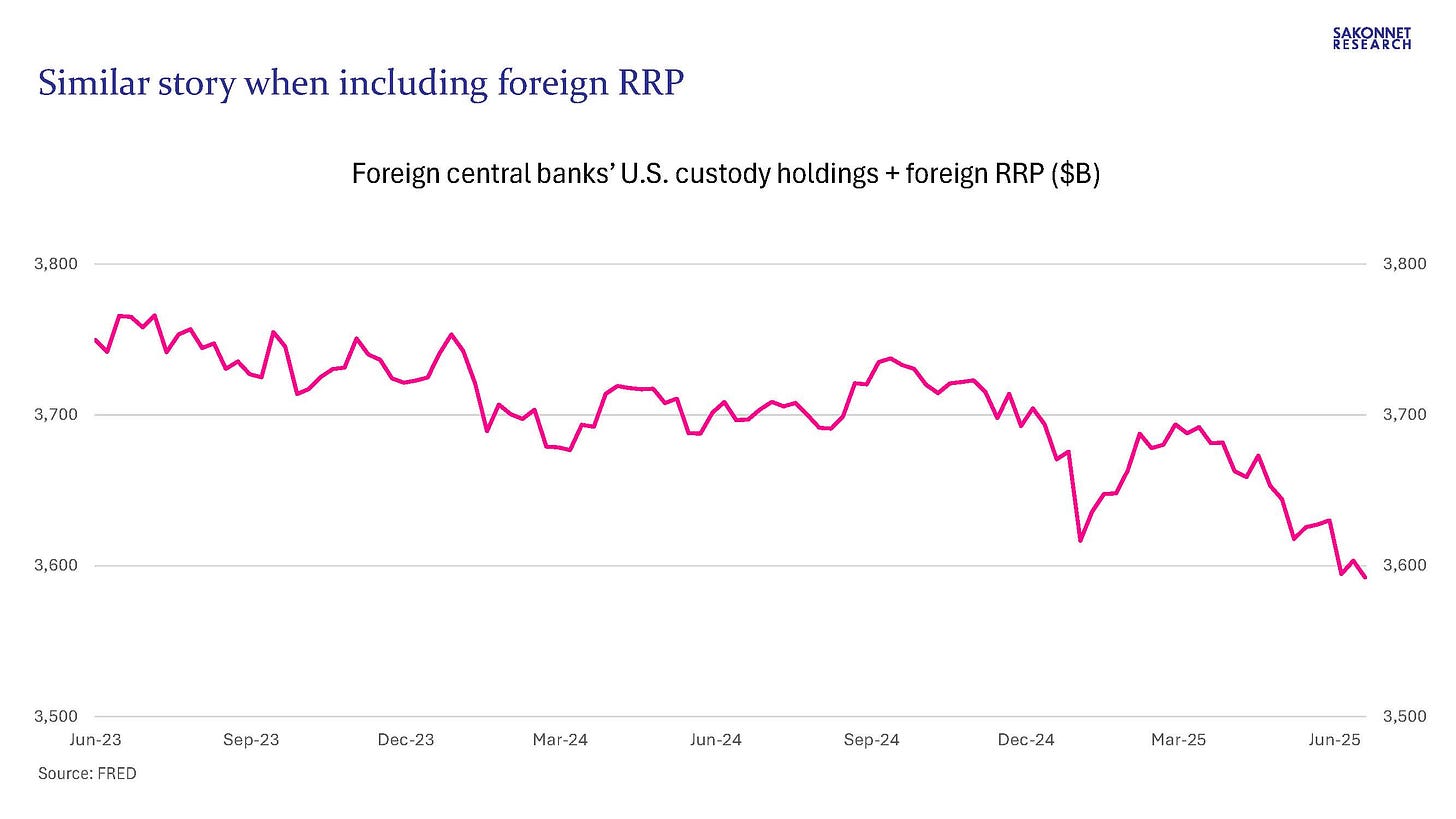

In other words, price-sensitive buyers (including hedge funds) are replacing price-insensitive ones in the world’s largest and most important bond market. The Fed continues to slowly reduce its U.S. Treasury holdings via its quantitative tightening (QT) program, and foreign official institutions (namely central banks and sovereign wealth funds) have done the same in recent years (link), a trend that could intensify post-Liberation Day as confidence in the U.S. diminishes. Indeed, the value of foreign central banks’ U.S. securities held in custody at the Fed is at an eight-year low, and the recent trend is the same when including their cash at the Fed’s overnight reverse repo (RRP) facility. An ongoing shift toward price-sensitive buyers could put upward pressure on short- and long-term U.S. government bond yields, bearing in mind that the latter remain near their 2007 highs despite the recent decline. Many important borrowing rates are tied to long-term government bond yields, including mortgage rates.

The BIS’s warnings about the increasing fragility of markets begs the question of what U.S. regulators are doing in response. An answer: proposing to reduce/weaken the enhanced supplementary leverage ratio (eSLR) that applies to the eight U.S. Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIBs) in an effort to support the functioning of the U.S. Treasury market. Two of the seven members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System voted against even requesting comment on the proposal, in a sign of how unpopular this proposal is in some circles.