The Latest on Drivers of Consumer Spending

Yes, the FOMC cut the federal funds rate last week, but there's more than that going on

I published an article two weeks ago on the drivers of U.S. consumer spending; my conclusion was that spending will likely remain under pressure for the foreseeable future, even if GDP continues to grow at a 2.5%-3.0% rate. I wrote that the drivers of consumer spending are the real economy (incomes, savings, borrowing, and net worth) and government assistance programs, the latter of which have been enormous post-COVID and directly boosted the former as well (in the form of temporarily higher incomes and savings). An update is in order following data releases over the past two weeks, the Fed meeting last week, and upcoming data revisions.

Net Worth

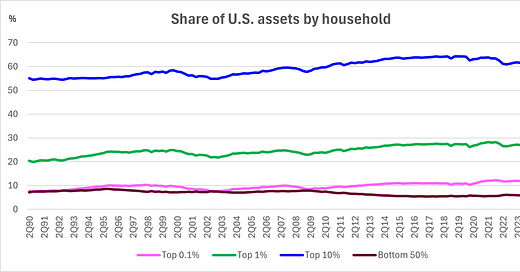

The Federal Reserve Board (the Fed) published its quarterly Z.1 report (Financial Accounts of the United States) on Sept. 12, which showed that household net worth increased by $2.8 trillion to a record high $163.8 trillion in 2024q2, once again driven by higher stock prices and home prices. A week later, the Fed updated the Distributional Financial Accounts, which provide a quarterly estimate of the distribution of U.S. household wealth. I wrote in my last piece that while household net worth is at a record high, the distribution of that wealth has limited its impact on consumer spending. As of 2024q2, the top 1% of households held 27.4% of assets and the top 10% held 62% of assets, compared to the bottom 50% with just 5.7%.

It’s no wonder, then, that many retailers and consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies exposed to the bottom 50% of households have been experiencing weak sales trends and, in many cases, cutting their full-year sales guidance in recent months. Dollar General and Dollar Tree are two examples, but there have been many others. Yes, Walmart has traditionally catered to low and middle-income shoppers and has had a fine year, but the company has benefited from broad market share gains, meaning more higher-income shoppers going there as they look to save money. Costco similarly focuses on value, and has thrived this year as well.

Incomes

I wrote in my last piece that income growth has been nonexistent for years: real average weekly earnings are barely higher than they were pre-pandemic (up just 1.5% since February 2020), and they have increased by just ~5% in almost ten years, since the beginning of 2015. On Thursday, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) will publish its annual update of the National Economic Accounts, which will result in revisions to the previous five years of GDP and related estimates. Given the recent substantial downward revision to the nonfarm payrolls data in the 12-month period through March 2024, I assume personal income will be downwardly revised as well; income comes from jobs. And GDP is linked to personal income given that GDP (the sum of final expenditures) = GDI (the sum of income payments and costs incurred in production). Income growth, as weak as it’s been, may have been even weaker than previously reported.

The Fed

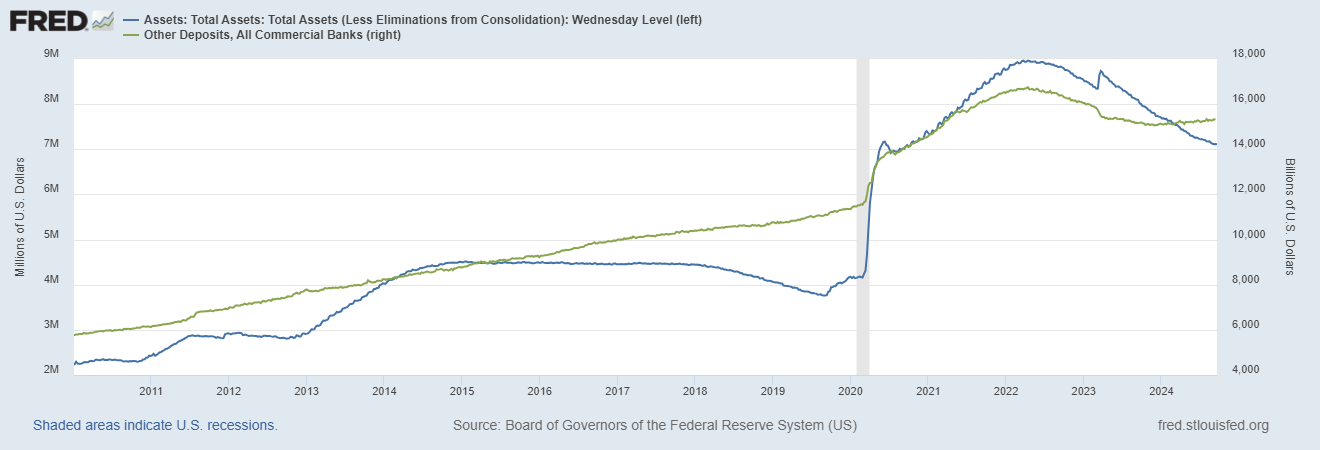

While the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided to reduce the target range for the federal funds rate by a greater-than-expected 50 basis points last week, it’s “not thinking about stopping runoff because of this at all,” meaning the Fed continues to shrink its balance sheet even as it’s begun an interest rate cutting cycle. As Chair Powell said, “[bank] reserves are still abundant and expected to remain so for some time.” Since the beginning of the Fed’s quantitative tightening (QT) program in June 2022, the Fed’s balance sheet has shrunk by $1.8 trillion while banks’ core deposits have fallen by $1.4 trillion.

So long as the Fed’s balance sheet continues to shrink, bank deposits are likely to continue to fall, and there’s an obvious relationship between deposits and loans (banks take deposits and make loans). Many economic and market observers are hoping the recent decline in interest rates will spur a surge in borrowing and spending, but that’s contingent upon banks’ ability and willingness to lend more. Credit quality is deteriorating, and banks’ Tier 1 capital levels (after adjusting for unrealized securities losses) have barely grown since the beginning of 2019. It’s also contingent upon the willingness of businesses and consumers to borrow more, bearing in mind that many are already indebted and uncertain of what’s to come. Banks’ loan growth has been slowing, not accelerating; the only source of rapid loan growth is loans to nondepository financial institutions (NDFIs) such as private credit firms, not the real economy.

For background on the Fed’s QT program, below is a chart comparing its securities holdings (which are directly affected by QT) to the combination of bank reserves and the Fed’s overnight reverse repurchase facility (ON RRP). The Fed’s balance sheet and bank reserves shot up owing to its numerous quantitative easing (QE) programs from 2009 onward; the former has been falling since the onset of QT in June 2022, dragging the combination of bank reserves and ON RRP down with it.

While the combination of reserves and the ON RRP facility have fallen since June 2022, the entirety of that decline has been concentrated in the ON RRP facility. As Chair Powell said last week, “The shrinkage in our balance sheet has really come out of the overnight RRP.” That’s why bank reserves remain as high as they are. As can be seen below, bank reserves have been unchanged since the onset of QT, and remain dramatically higher than they were pre-COVID. An obvious question is what level of bank reserves is necessary or appropriate given where they’ve been historically.

Conclusion

With its ongoing QT program, the Fed is effectively removing liquidity from the banking system and economy, the opposite of what happened in the immediate aftermath of COVID. With the Fed removing liquidity, real income growth virtually nonexistent, personal saving rates near historic lows, bank lending growth to the real economy slowing, and household wealth skewed to a small segment of the population, the likelihood of a borrowing and spending surge just because interest rates have fallen strikes me as low.