What Will Generate the Next Consumer Spending Upswing Other Than More Government Stimulus?

Incomes and bank lending have stagnated and saving rates are low and falling

I posed this question at the end of my first Substack post. Let me attempt to answer it.

The drivers? The drivers will be the real economy and the government. The real economy consists of incomes/wages, savings, borrowing, and net worth. The government contributes assistance programs, some of them effectively financed by the Federal Reserve (Fed), including the historically large deficit spending on COVID-19 assistance programs. In this article I’ll discuss both the real economy and the government. The data suggest that the near-term future of consumer spending looks poor, bearing in mind that another deficit-financed government stimulus program may create more problems than it fixes. While household net worth is at a record high owing largely to surging stock prices, the distribution of that wealth has limited its impact on consumer spending.

Incomes Haven’t Been Growing

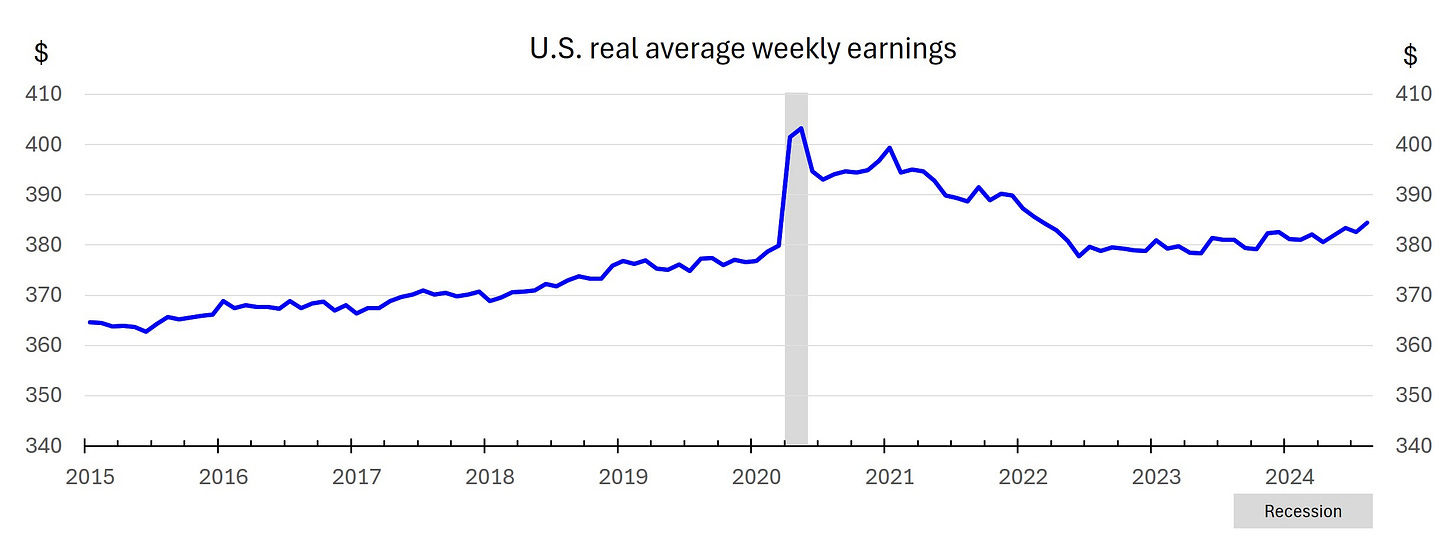

Income growth, the obvious source of spending power, has been nonexistent in recent years. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes a monthly release on real (inflation-adjusted) earnings, which includes real average hourly earnings and real average weekly earnings. I focus on the latter because it incorporates changes in the average workweek, which has been in a steady decline over the past three years. Real average weekly earnings are barely higher than they were pre-pandemic (up just 1.5% since February 2020), and they have increased by ~5% in almost ten years, since the beginning of 2015.

Saving Rates Are Near Record Lows

Given that Americans’ real incomes haven’t grown for years, it stands to reason that saving rates would be low. (The personal saving rate is the percentage of people’s incomes left after they pay taxes and spend money.) Indeed, the saving rate is near the lowest it has ever been (at 2.9%).

Government Assistance Programs Drove Consumer Spending Higher in Recent Years, But Those Days Are Over

Incomes and saving rates skewed dramatically higher during the pandemic thanks to government stimulus programs. Direct payments totaled $860 billion, and that amount was a fraction of the total COVID-19 related government relief of nearly $5 trillion, according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

In the aftermath of these COVID-19 government assistance programs, several branches of the Fed wrote about the “excess savings” that Americans accumulated during the pandemic. That discussion has since stopped, since all manner of economic data and corporate earnings data have shown that a large and growing segment of the population is cash-strapped.

Now that the positive effects of the last big government stimulus program have worn off, will there be another? The economy appears incapable of growing at a healthy clip without heavy government spending. True, gross domestic product (GDP) has grown at a 2.5%-3.0% rate in the past two years, but government spending has accounted for 25% of that growth, just as government hiring has been crucial to employment growth. Over the past year, government and healthcare accounted for 50% of the net change in employment: government was 21% and healthcare 29%.

Is it reasonable to count on the government to come to the consumer’s rescue again? In the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) latest projections, it will run a budget deficit after adjustments of $2 trillion in fiscal year 2024, equal to 7% of GDP. CBO is projecting similar deficits as a percentage of GDP through 2034, significantly higher than the 3.7% that deficits have averaged over the past fifty years. Ongoing deficits that large mean the government has less to spend on discretionary items because of ballooning interest expense on the rising debt.

Net interest payments likely aren’t stimulative to consumer spending to any appreciable extent. Why? When the government runs budget deficits, other parties need to finance them. Of the government debt held by the public as of December 2023, two-thirds was held domestically and the remaining one-third was held by foreigners. (This data is courtesy of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation.)

The interest expense on the domestically held debt gets paid to the Fed, mutual funds, banks, state and local governments, pension funds, and insurance companies. In other words, an increasing percentage of government spending is being diverted from consumers’ pockets into institutional ones, and that doesn’t stimulate spending. (Government money market funds are mainly held by institutions, not retail.)

The coming elections will play an important role. A sweep of all three branches of government will give either party greater ability to pass spending programs, and the opposite holds true if government remains divided. The Trump tax cuts are set to expire at the end of 2025; if they’re allowed to expire, income taxes will rise for most households, crimping their spending power.

Furthermore, lawmakers have until Sept. 30 to pass legislation to prevent a government shutdown in early October. In a shutdown, mandatory spending continues, but the roughly 25% of government spending subject to annual appropriation by Congress does not.

Consumer Debt is Still Growing, But At a Much Slower Pace

According to the latest Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit from New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data, there was $17.8 trillion of consumer debt outstanding as of 2024q2. It grew by 0.6% sequentially, which represents a slowdown from the preceding eight-quarter growth rate of 1.4%.

The biggest percentage increase was in credit card loans, up 2.4% sequentially. What about credit quality? The trends aren’t encouraging. As the New York Fed noted, auto and credit card delinquency rates remain elevated: over the past year, 9.1% of credit card loans and 8.0% of auto loans transitioned into delinquency. Related or not, the recent rate of consumer loan growth is barely above zero.

Other types of bank lending to the real economy have stagnated as well. Bill Moreland of BankRegData pointed out in a recent article that net bank loans excluding those to nondepository financial institutions (NDFIs) grew by only $47.5 billion sequentially in 2024q2, which equates to just 0.4%. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) noted the same trend in its recently published Quarterly Banking Profile for 2024q2.

Why the slowdown in banks’ loan growth to customers other than NDFIs? My assumption is deteriorating credit quality along with their capital levels. I addressed the former. Regarding the latter, banks’ asset growth is tied to their regulatory capital levels. As explained in a March 2023 piece by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) titled “Bank Capital Requirements: A Primer and Policy Issues,” regulators require banks to hold capital to reduce the likelihood of bank failures, given the risk those failures pose to financial stability and to the economy.

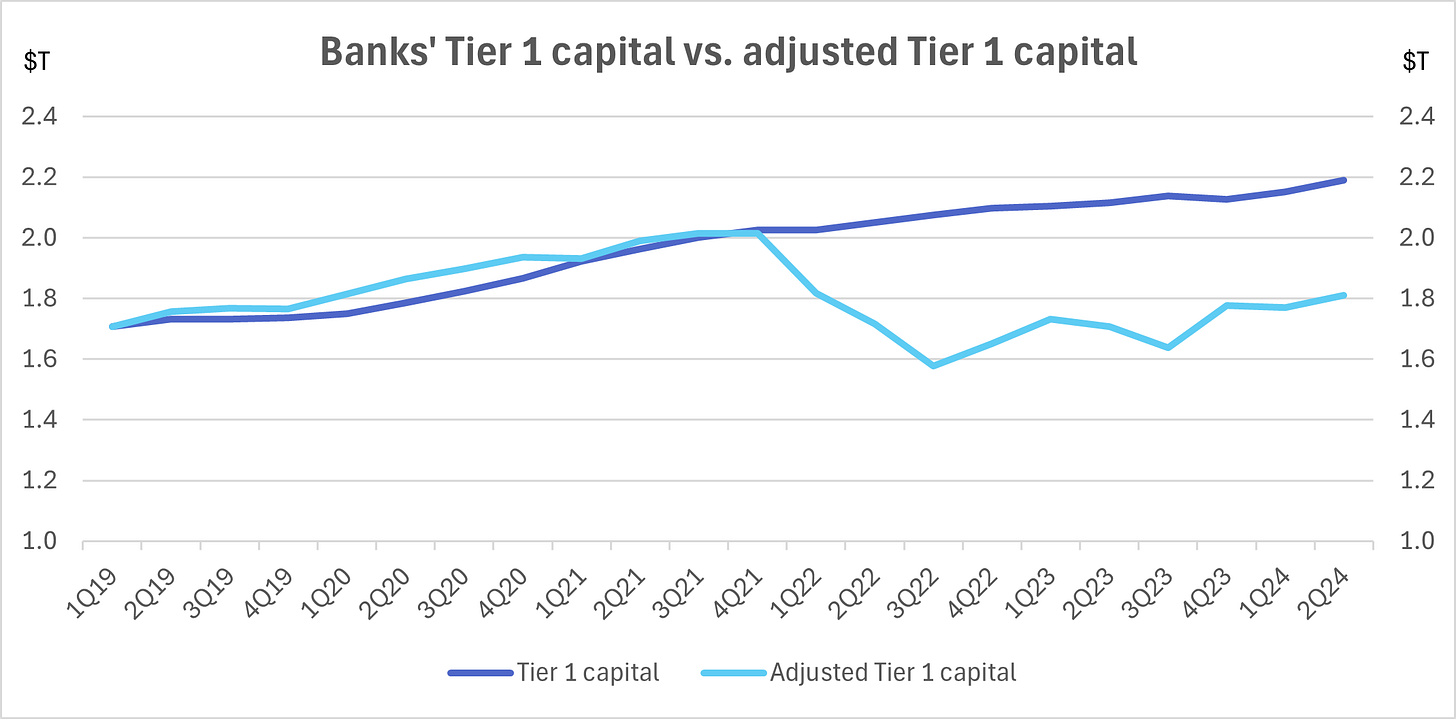

If banks’ capital isn’t growing, their assets (the biggest component of which is loans and leases) can grow only so much before their capital ratios get too low. So-called Tier 1 capital is the strongest form of bank capital. Since the beginning of 2019, Tier 1 capital has grown by 28%. However, Tier 1 capital mostly excludes banks’ unrealized losses on their available-for-sale (AFS) and held-to-maturity (HTM) securities, which as of 2024q1 represented nearly 25% of Tier 1 capital.

Adjustments need to be made to unrealized losses, because a small fraction of them (~5%) are already reflected in Tier 1 capital via certain banks’ accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI); see here for more details. When I made those adjustments, unrealized losses still represented nearly 20% of Tier 1 capital. What was the impact on Tier 1 capital? Instead of having grown 28% since the beginning of 2019, the adjusted number only grew 6%. Indeed, the KC Fed noted in its 2023q2 economic review that banks’ unrealized losses were negatively correlated with loan growth, meaning the former adversely affected the latter.

There’s growing anecdotal evidence that some banks are capital-constrained, as well. Their use of a tool called synthetic risk transfers (SRTs) is one sign. As S&P Global Market Intelligence wrote in April, “SRT activity is increasing as banks seek to obtain regulatory capital relief and manage their risk exposures.”

Another sign is recent asset sales and other sources of funding. In May, Truist sold its remaining stake in the fifth largest insurance brokerage in the U.S. for $10.1 billion, which mostly offset the negative impact of selling $27.7 billion of underwater AFS securities for an after-tax loss of $5.1 billion. These moves prompted Moody’s to downgrade Truist’s credit ratings the following day. A day after Truist’s sale, Commerce Bancshares announced a stock transaction that resulted in a $177 million gain, which essentially offset a loss of $179.1 million stemming from selling underwater AFS securities. And KeyCorp recently received an investment that has enabled it to “pull forward” additional net interest income (NII) by selling some of its underwater AFS securities; Scotiabank announced in August that it would acquire 14.9% of KeyCorp for $2.8 billion. KeyCorp announced on Sept. 9 that it sold $7 billion of low-yielding securities that will likely result in an after-tax loss of $700 million in 2024q3. The bank is “contemplating” selling low-yielding securities that would result in an after-tax loss equivalent to half of Scotiabank’s investment.

Net Worth Is At a Record High, But That’s of Little Help to Most Americans

U.S. household wealth hit a new record high in 2024q1, with net worth (assets minus liabilities) hitting $160.8 trillion according to the Fed’s Z.1 report published in early June. Higher stock prices contributed the lion’s share (75%) of the sequential improvement.

However, the distribution of the net worth is equally important. The FRED blog published a chart in April based on Fed data that plots real assets across households over time. What the chart shows, among other things, is that the top 0.1% of households held $6.5 trillion in real assets as of 2023q4, more than double the amount of assets held by the bottom 50%. The top 1% of households held 27% of assets as of 2024q1, compared to the bottom 50% with just 6%.

The Fed Giveth, the Fed Taketh Away

I’ve addressed numerous direct contributors to consumer spending, including government assistance programs. What I haven’t addressed is the Fed’s role in those government assistance programs. The Fed effectively financed the government’s massive deficit spending during COVID-19 via its quantitative easing (QE) program. Its securities holdings went from $3.8 trillion in February 2020 to $8.5 trillion in early 2022, a nearly $5 trillion increase. Readers may recall from earlier that the government spent $4.6 trillion in total COVID-19 relief funding, such that the Fed bought securities nearly equivalent to the government’s spending on COVID-19 programs. Unfortunately, 40-year high inflation ensued, so it embarked on its most aggressive interest rate tightening cycle in decades. Given what happened last time, the Fed may be reluctant to finance future stimulus programs, because its dual mandate by law is maximum employment and stable prices. Furthermore, even as it appears poised to start cutting interest rates, its quantitative tightening (QT) program continues.

I wrote that the Fed effectively financed the government’s massive deficits during COVID-19 because it doesn’t buy new Treasury securities directly from the U.S. Treasury. As the Fed has explained, The Federal Reserve Act specifies that it may buy and sell Treasury securities only in the “open market.” It meets this statutory requirement by buying and selling securities through so-called primary dealers. Technically, then, the Fed didn’t directly finance the government’s COVID-19 deficit spending; nevertheless, it effectively did so by buying nearly $5 trillion of Treasury securities from primary dealers (who act as an agent for other parties).

It’s worth explaining how banks’ balance sheets are affected by the Fed’s QE and QT programs. An article from Liberty Street Economics from 2017 went into detail on this topic, and a paper in 2023 elaborated on it. When the Fed buys Treasury securities from nonbanks (mutual funds, insurance companies, etc.), bank deposits and balance sheets expand as the nonbanks deposit the Fed’s payment in their bank. And the reverse is true with QT, in that bank deposits fall.

What may be helpful is an illustration of what happened in the COVID-19 period. In the following graph, the Fed’s total assets are on the left and commercial banks’ total assets are on the right. The Fed’s securities holdings increased by $4.7 trillion from February 2020 to March 2022, while banks’ assets increased by a virtually identical amount.

Banks’ deposits have been falling since the Fed embarked on its QT program in June 2022, particularly their “core”/other deposits (which exclude time deposits such as CDs). The Fed’s balance sheet has shrunk by $1.8 trillion since June 2022, while banks’ core deposits have fallen by $1.4 trillion.

What are the implications for the future of bank deposits and therefore lending? The Fed’s QT program continues, albeit at a reduced pace since June. So long as it does, bank deposits are likely to continue to fall, and there’s a clear relationship between deposits and loans.

Conclusion

I examined the drivers of consumer spending: nearly all are moving in the wrong direction, with the exception of net worth. Real incomes have stagnated for years. Saving rates are near record lows. Consumer borrowing is slowing despite the aforementioned historically low saving rates. Prospects of another large government stimulus program are unclear, and there are constraints on discretionary government spending including ballooning interest expense. Furthermore, any future large government spending programs could push up inflation, as happened during the pandemic; real incomes took a sizable hit when that happened. While net worth is at a record high, that’s not helping most Americans.

I welcome feedback on any other potential drivers I may be overlooking.