What Happened to the Growth in Bank Deposits?

Also, an update on recent bank commentary on credit line draws

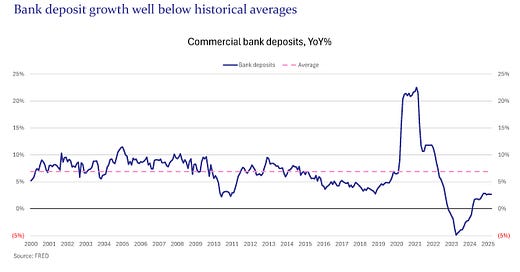

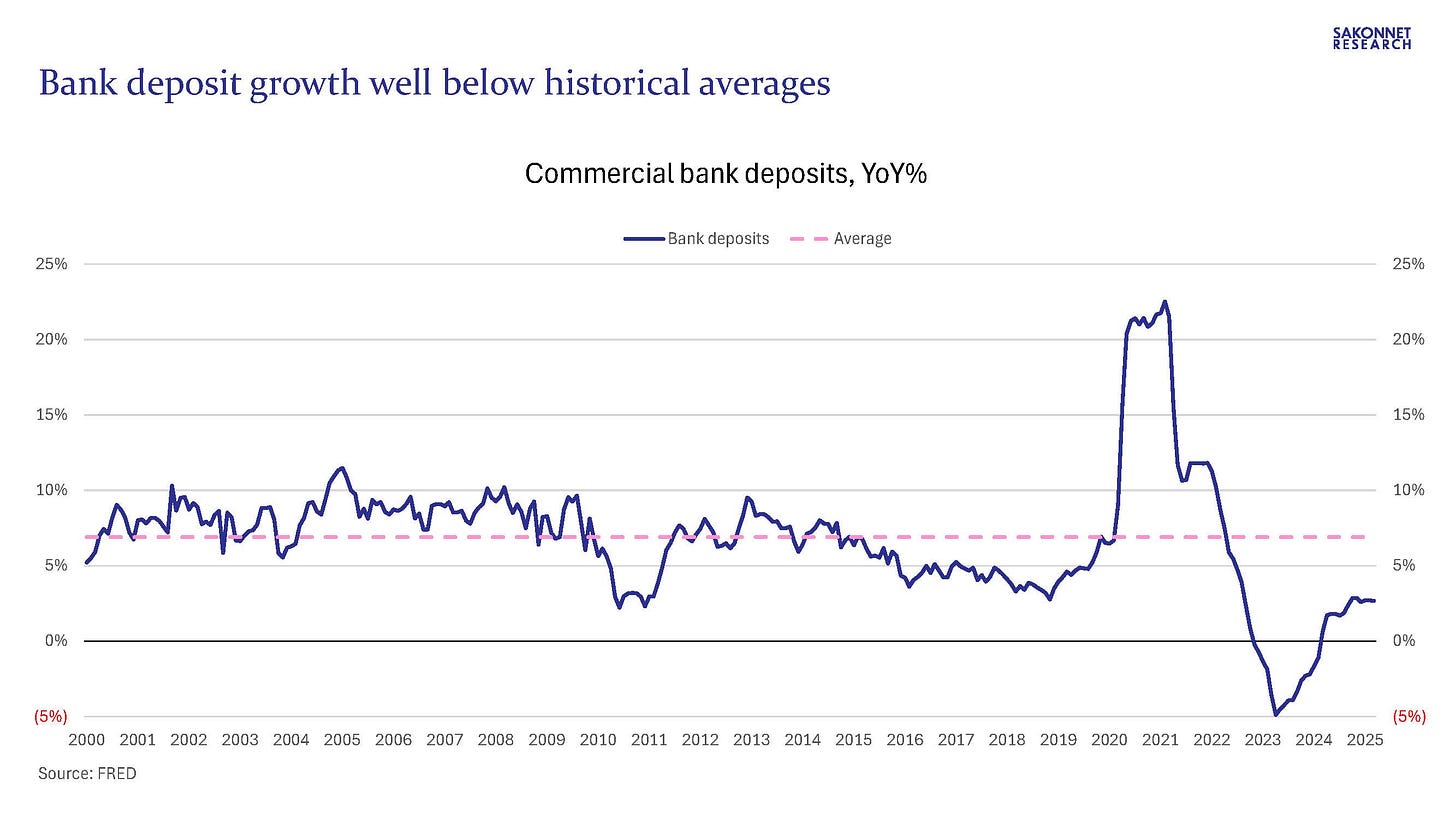

In my last post I wrote about U.S. banks’ loan trends, specifically the disproportionate amount of lending going to levered nondepository financial institutions (NDFIs) as opposed to real economy borrowers (meaning households and businesses). This time I’ll focus on their deposit trends. From 2018 to February 2020, deposit growth averaged 4-5%, considerably below the 2000-2017 rate of 7.2% but nonetheless much better than what followed the pandemic spike. COVID distorted the trend as it did so many others, as the Federal Reserve’s massive asset purchase/quantitative easing (QE) program, a historic amount of commercial and industrial (C&I) credit line drawdowns and a historic amount of government stimulus spending led to an unprecedented increase in bank deposits, from $13.3 trillion in February 2020 to $18 trillion by the end of 2021. (In simple terms, when the Fed buys securities from investors via QE, investors deposit the cash into their bank accounts, creating deposits. As Fed staffers explained it in 2022, “The asset purchases by the Federal Reserve led to the creation of reserves in the banking system, and, to the extent that the Federal Reserve purchased the assets from nonbank entities, they also led to the creation of deposits.”)

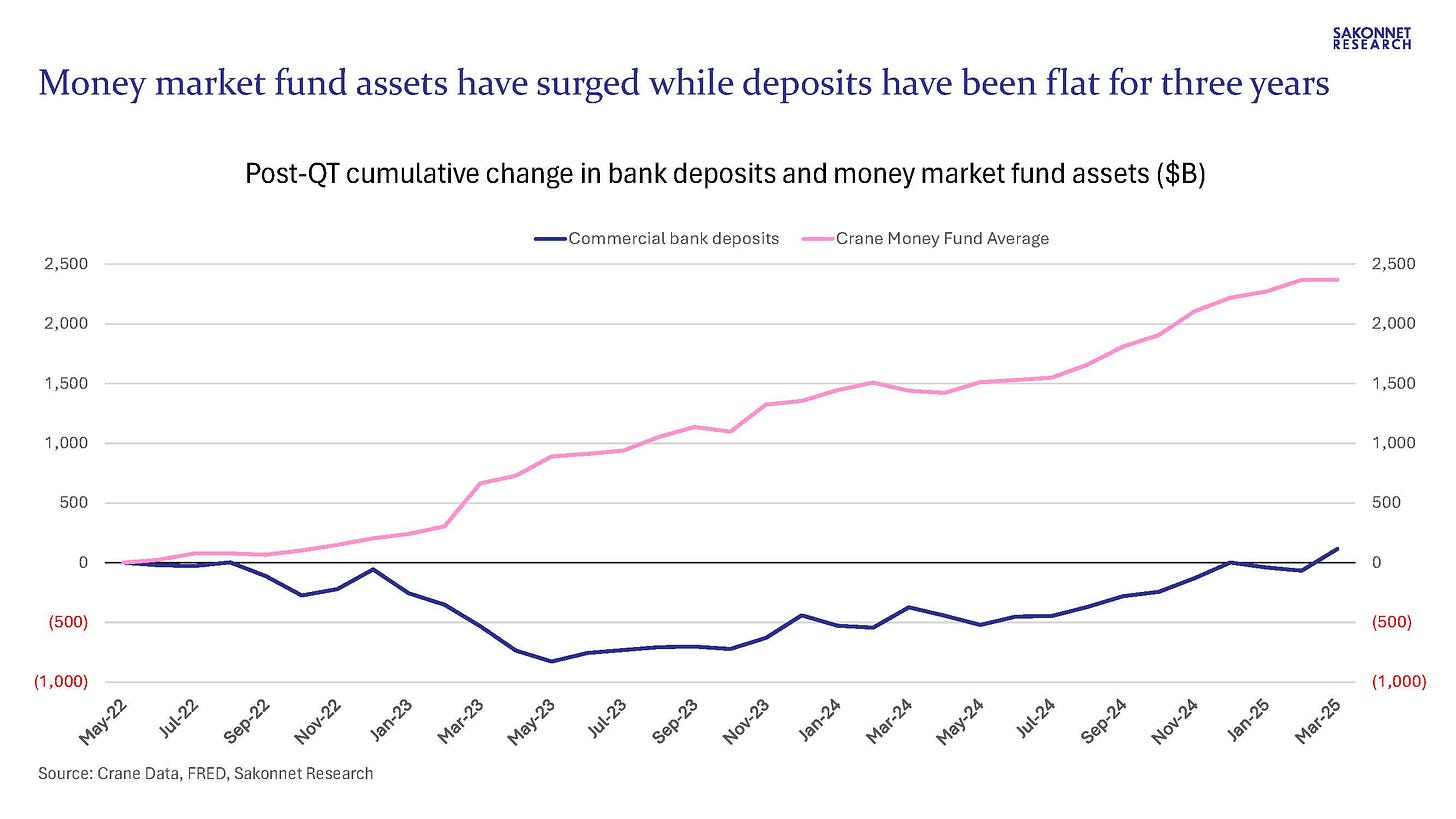

When the Fed started reducing its asset holdings in mid-2022 via its quantitative tightening (QT) program, bank deposits fell for the following year, from $18 trillion to just over $17 trillion. They’ve since recovered to just over $18 trillion, effectively unchanged versus three years ago. Deposits began growing on a year-over-year basis last March, but the average growth rate has only been around 2%, far lower than the historical growth rate.

Just as bank loan growth has been unusually weak over the past two years (even with booming lending to NDFIs), so too has deposit growth. What explains the latter? Likely to a significant extent, QT and the growth of money market funds (MMFs). Just as QE created deposits, QT has done the opposite. And as I wrote about in my last post, MMFs have grown rapidly over the past few years. Money is a commodity, and as such it often goes whenever institutions and retail can earn the most attractive rates. And the rates on MMFs are far more attractive than what banks are paying on savings accounts. The Crane 100 Money Fund Index’s 7-day yield as of March-end was 4.15%, compared to the Crane Brokerage Sweep Index’s yield of just 0.41%. Per the FDIC (link), the national deposit rate on savings accounts is an identical 0.41%. For any yield-sensitive institution or retail investor with the ability to move excess funds, the choice seems clear.

Bank deposits are the fuel for loans, and deposit growth has likely been limited by the relative attractiveness of MMFs. Furthermore, the economy’s recent deterioration will likely further limit deposit growth and therefore loan growth, bearing in mind that loan growth to the real economy has already slowed to abnormally low levels excluding the pandemic period. Please see charts below for supporting data.

What’s one possible source of a sudden pickup in loan growth? Another big drawdown of companies’ credit lines. I wrote in my presentation last week about the historic spike in C&I loans in March 2020 as companies drew on their (committed) credit lines at the outset of COVID; the Fed’s QE program funded that draw by creating deposits. It’s far from clear what would fund any future such draw if the Fed doesn’t resort to QE again, bearing in mind that the Fed continues to slowly shrink its still-large balance sheet. I’m not the only one thinking about the issue of companies drawing on their credit lines; several banks have either been asked this question or volunteered such information on their 1Q25 results calls over the past few days, presumably given its importance to the economy and the health/stability of the banking industry. I’ve bolded certain lines for emphasis:

JPMorgan Chase:

Question on the wholesale loans. I'm going into this because I noticed your average loan growth, I think it was running at about 2% year-on-year and then end-of-period loans was up 5% and wholesale loans was up 7%. So I'm just wondering if there was some line drawdowns at quarter-end and it's a broader question on just liquidity. Do you see your customers looking for more liquidity? Are they drawing down lines? And maybe if you could speak to liquidity in the front-end of the market, that'd be helpful too. Thank you.

Yeah, it's a good question, Betsy. So a couple of things. One is in our soundings of our wholesale clients during sort of the moments of peak uncertainty, we did hear them talking about wanting to focus on shoring up liquidity. Interestingly, I actually asked the question like a day ago, whether we were seeing draws, meaning -- meaningfully observable draws from clients. And the answer to that question was no, at least not yet. So I don't know what to make of that, but perhaps it suggests that we do not see, you know that level of heightened anxiety that people are more just focusing on addressing their supply chain issues right now.

Wells Fargo:

So on the draws, we're monitoring it really, really closely, both on the commercial banking side and the CIB side. There's been one -- I mean, literally one draw that we've actually talked about, and we don't really think it relates to COVID. But quite frankly tariffs. Definitely sorry, related to COVID. We don't think it relates to tariffs. It's just the situation of that company and not something that anyone is worried about. But it just gives you a sense for how actively we're monitoring draw activity. The moment it happens, we're talking about it. There's communication across everything.

PNC:

Yes. It's interesting. In all the dialogue that I've kind of had with clients, nobody is saying they're purposely building inventory in advance of the tariffs. Having said that, most of our lines finance working capital.

So almost definitionally, there's some inventory build going on.

Citizens:

Commercial loans were up slightly with a modest increase in line utilization as some of our corporate banking clients drew down on their lines to finance inventory builds ahead of tariffs. We saw a modest increase in capital call line usage given M&A activity in our sponsor base.