Whither Government Transfers, Which Have Propped Up Consumer Spending Post-COVID?

Even if the incoming administration doesn't cut Medicaid payments, consumer spending on all manner of discretionary items is likely to remain under pressure

A week ago, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City published an economic bulletin highlighting the impact of abnormally large government transfers during the pandemic on personal incomes and consumer spending. The KC Fed noted that in times of economic stress, the federal government often does what it deems necessary to support the U.S. economy, and when the economy recovers the government tends to reduce its stimulus measures, lowering the federal deficit. However, this pattern has changed over the past 15-20 years. After the 2007-09 financial crisis, the federal government deficit remained elevated even when unemployment rates did not, and post-COVID, federal government spending and deficits have remained at historically high levels even after the U.S. reached full employment. The KC Fed indicated that the shift toward “more sustained government spending during recoveries has been driven by higher transfers.” Transfers that individuals received from federal, state and local governments increased from about 4.5% of GDP in 1960 to 15.0% of GDP by the first half of 2024. During and after the pandemic, historically large government transfers supported an increase in personal spending/PCE from 67% of GDP in the second half of 2019 to 67.8% in the first half of 2024.

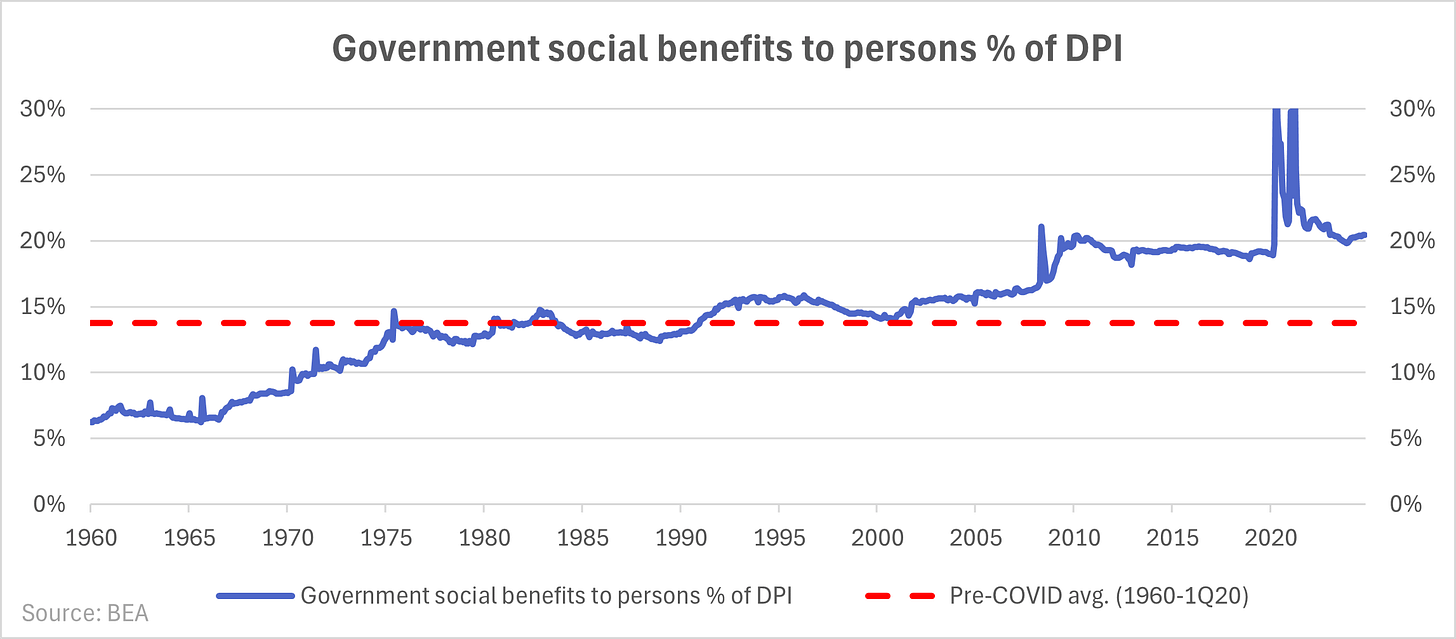

While government transfers surged during the pandemic, the shift in the composition of personal income toward government transfers has been a long-term trend, under many administrations. (The chart below is through 2024q3.)

The trend continued in October, per the “Personal Income and Outlays” report from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Government transfers accounted for 20.4% of disposable personal income (DPI), up from 20% at year-end 2023 and well above the pre-COVID (1960-1Q20) average of 14%.

The incoming administration announced an outside advisory group with the goal of reducing what it deems wasteful spending, and numerous news outlets have reported that Republicans may consider significant cuts to Medicaid. However, doing so won’t be easy. Per The Wall Street Journal, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated in June that 56% of Medicaid benefits in fiscal 2024 would go toward the aged, blind and disabled, and the article noted that many nursing homes receive a substantial share of their revenue from the program. The article noted that only 14% ($948 billion) of government spending last fiscal year was on nondefense discretionary categories, highlighting the difficulty of cutting government spending in a meaningful fashion.

Given the outsized role that government transfers have played in supporting consumer spending and therefore GDP growth in recent years, it’s worth considering what would happen to consumer spending if some of these programs were to be reduced. Even under the assumption that none of them is, though, there’s already a discretionary consumer spending problem. U.S. retailers are reporting flat comparable sales this year, with the trends getting worse rather than better. The trends in restaurant sales are little different, as is evident in the publicly-traded restaurant operators’ results and indicators such as those from the National Restaurant Association. Side note: my retailer universe excludes e-commerce retailers such as Amazon and Wayfair, but most retailers include e-commerce growth in their comparable sales figures, and e-commerce sales as a whole only contributed ~1 point to retail sales growth in 3Q (e-commerce accounted for 16.2% of retail sales, and it grew by 7.4% YoY).

So on what basis have you been reading about a “strong” consumer? Real (inflation-adjusted) consumer spending/PCE grew 3% YoY in October and is up nearly that much year-to-date. So what’s the problem? The composition of that growth. I wrote last week that nearly 50% of real PCE growth over the past two years through 2024q3 came from health care spending, compared to the ~23% of real PCE that health care spending accounts for. In other words, health care is accounting for a disproportionate and growing percentage of consumer spending, and health care is a mandatory rather than a discretionary category. Along similar lines, “financial services and insurance” excluding health insurance (I’ve included health insurance in health care spending) accounted for another 13% of real PCE growth over the past two years, compared to the 6% of real PCE that it accounts for. The consumer spending economy is being driven by health care and financial services and insurance, all mostly if not entirely mandatory items.

Those who read the release highlights from the aforementioned October BEA release on personal income and outlays may have noticed this trend. Consumer spending was up $72.3 billion in October from the previous month, with the entirety of the increase coming from services (goods spending was down). And within services, the largest contributors to the increase were health care, housing and utilities, and financial services and insurance.

It’s no wonder, then, that retailers, restaurant chains, and consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies alike are experiencing such weak sales trends. And there’s little reason to expect this trend to change anytime soon. Said J.M. Smucker last week, “Consumers continue to be selective in their spending, largely driven by inflationary pressures and diminished discretionary income, causing the sweet baked goods category to recover slower than we have anticipated. These trends are causing a reduction in all channels, inclusive of convenience.” Numerous other retailers, restaurant operators and CPG companies have said much the same in recent weeks and months.