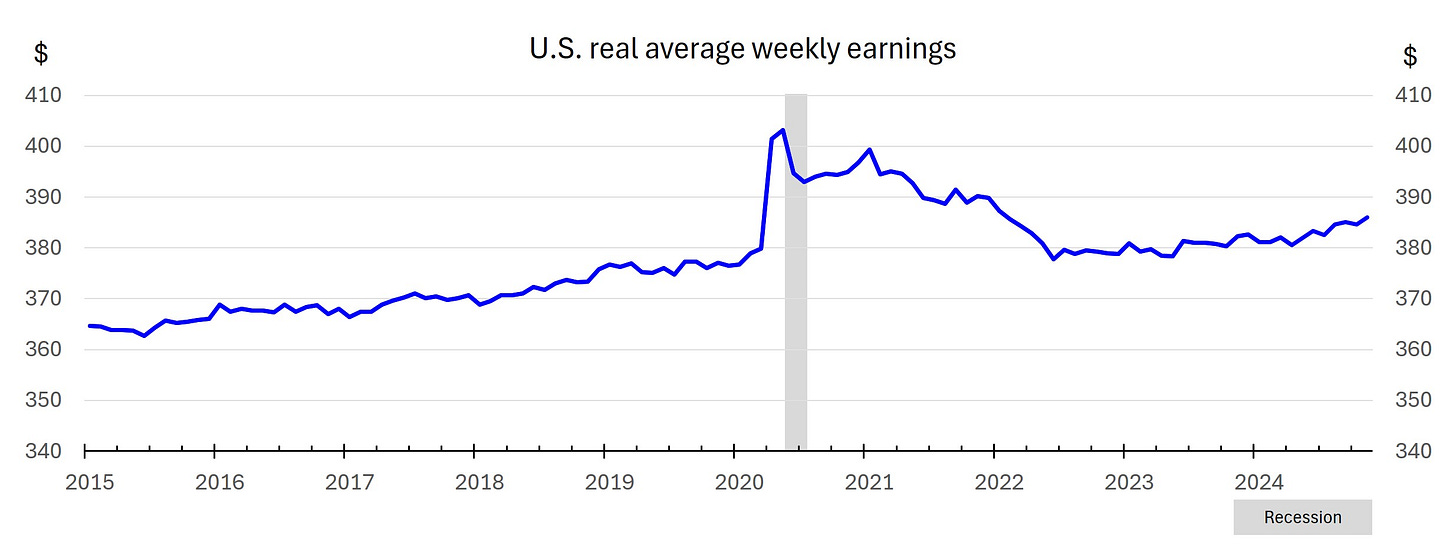

Real Average Weekly Earnings Remain Stagnant Post-Pandemic

The divergence between earnings and household net worth continues to grow

This morning, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) published real earnings data for the month of November. The headline was that real (inflation-adjusted) average hourly earnings were flat and real average weekly earnings were up 0.3% from October to November, the latter owing to a 0.3% increase in the average workweek. Since February 2020, real average weekly earnings are up just 1.9%, such that they’ve barely grown in the nearly five years since the pandemic began. They’re up a mere 6% since the beginning of 2015.

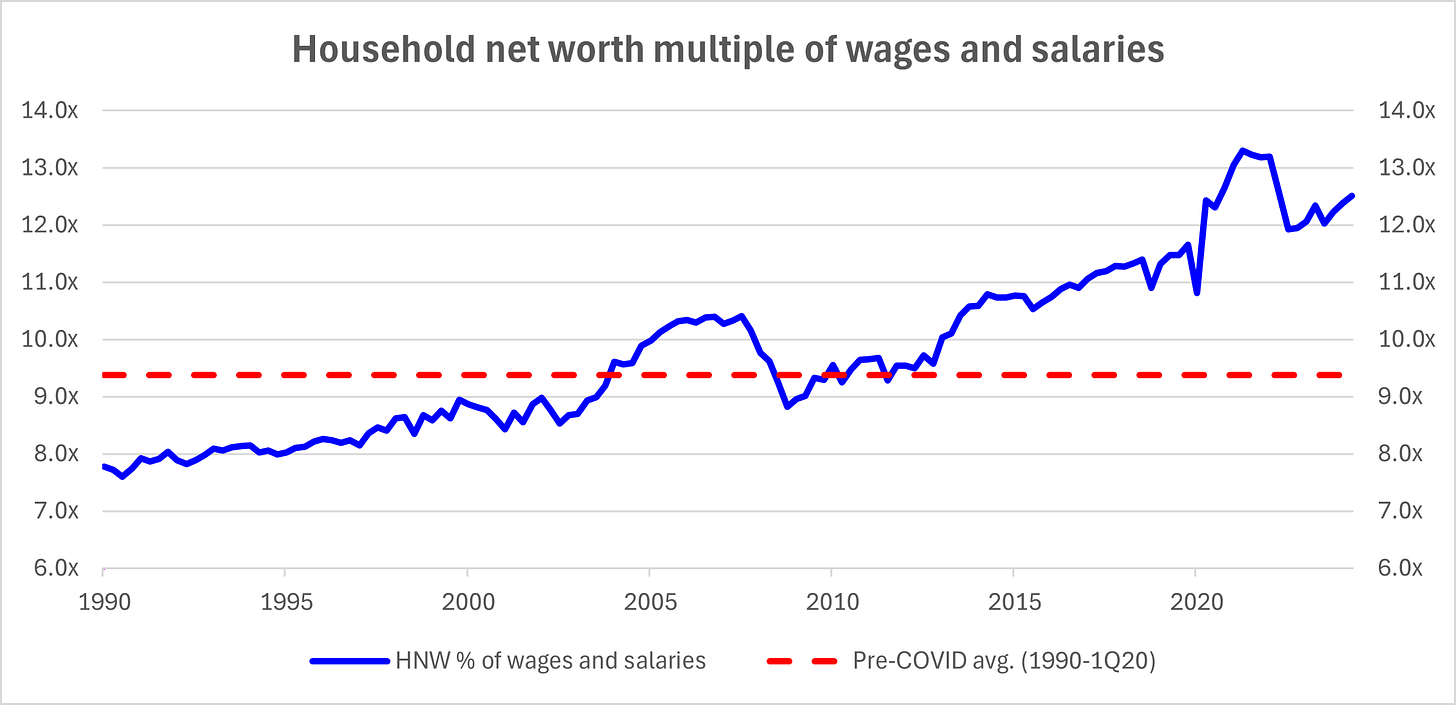

While Americans’ inflation-adjusted earnings have barely budged for years, their net worth keeps hitting new record highs, reaching $163.8 trillion in 2024q2. Why? Ever-rising stock prices and home prices. While household net worth is at a record high, the distribution of that wealth has limited its impact on consumer spending. As of 2024q2, the top 1% of households held 27.4% of assets and the top 10% held 62% of assets, compared to the bottom 50% with just 5.7%.

One way to visualize the gap between what Americans are earning and what they’re worth is to compare household net worth to wages and salaries. The former comes from the Federal Reserve’s Z.1 report (Financial Accounts of the United States), the latter from the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ (BEA) monthly release titled “Personal Income and Outlays.” The most prominent income measures from the personal income release are personal income (PI) and disposable personal income (DPI). However, both include government transfers called “government social benefits to persons” such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, which have become an ever-larger percentage of PI/DPI in recent years/decades (link) and don’t reflect what Americans are earning via their jobs.

When I compared household net worth to wages and salaries, I found that the former is 12.5x the size of the latter, compared to less than 8.0x times in 1990; the only time the multiple’s been higher was briefly during the pandemic.

Historically large government transfers have supported consumer spending and therefore the economy post-pandemic, but they aren’t a sustainable source of economic growth. Much the same goes for asset prices; they don’t always move in one direction, and even when they go dramatically higher as has been the case over the past two years, their impact on the economy is muted by the narrowness of asset ownership in this country. We’re living in a two-track economy: the top 1%/top 10% and everyone else. That explains why all manner of retailers, restaurant chains and consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies are experiencing chronic sales weakness amid pressure on discretionary spending (link) despite record household net worth.